Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Guadalupe

A wife of noble character who can find?

She is worth far more than rubies.

PROVERBS 31:10

1819William Bill Hansberry, great-grandfather, born at the Salubria plantation in Culpepper County, Virginia.

1895Carl Augustus Hansberry, father, born in Gloster, Mississippi.

1898Nannie Louise Perry, mother, born in Columbia, Tennessee.

191418 Carl Augustus Hansberry and future wife, Nannie Louise Perry, arrive in Chicago as part of the Great Migration from the South.

1919Carl Augustus Hansberry and Nannie Louise Perry wed in Chicago.

1930Lorraine Hansberry born in Chicago; her parents and three siblingsCarl Jr. (1920), Perry (1921), and Mamie (1923)reside in Bronzeville, on Chicagos South Side.

1937The Hansberrys move to all-white Woodlawn, where they are met with violence and hostility; the unrest leads to a civil rights lawsuit filed by Carl Augustus Hansberry.

1940U.S. Supreme Court rules in favor of Hansberry.

1946Carl Augustus Hansberry dies in Mexico.

1948Lorraine Hansberry enrolls at the University of WisconsinMadison, as a pre-journalism major; comes to the attention of the FBI for associating with Communists.

1950Drops out of the University of Wisconsin, studies briefly at Roosevelt College, and moves to New York City.

1951Begins writing for Paul Robesons Freedom newspaper in Harlem; also begins writing for several Marxist-socialist newspapers under pen names.

1951Engaged to Roosevelt Rosie Jackson, a Harlem street speaker and member of the Labor Youth League.

1952Secretly attends the Montevideo Inter-American Congress for Peace, in Uruguay, in place of Paul Robeson, who has been forbidden by the U.S. State Department from traveling abroad. Teaches black literature at the Marxist Jefferson School of Social Science.

1953Marries Robert (Bob) Nemiroff; moves into his apartment on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village.

195354 On staff during summers at Camp Unity, in upstate New York, a Communist-affiliated family camp.

1954Studies colonialism and Pan-Africanism under W. E. B. Du Bois; also becomes a regular speaker at rallies for social causes.

1956Nemiroff cowrites a hit song, Cindy, Oh Cindy. The money allows Lorraine to quit working part-time jobs in Greenwich Village and write full-time.

1957She completes the play A Raisin in the Sun.

1959A Raisin in the Sun opens in New Haven in January; continues to Philadelphia; and reaches Broadway in February. Hansberry becomes the first black playwright to win a Drama Critics Circle Award. Columbia Pictures purchases film rights and asks her to write the screenplay. Hansberry is part of a circle of lesbian friends. She moves to 112 Waverly Place in Greenwich Village, where she meets and falls in love with Dorothy Secules. Hansberry and Nemiroff continue to collaborate on Lorraines plays.

196064 Hansberry, now a leading black intellectual, is regularly invited to participate in public events and on television and radio.

1964Nemiroff quietly obtains a divorce in Mexico. Hansberrys health is very poor after several operations for an ulcerated stomach and pancreatic cancer. She enters the hospital critically ill in October.

196465 Hansberrys second Broadway play, The Sign in Sidney Brusteins Window, after a troubled opening, continues to run with donations and fundraising until the day of Lorraines death.

1965Hansberry dies of pancreatic cancer in New York City on January 12.

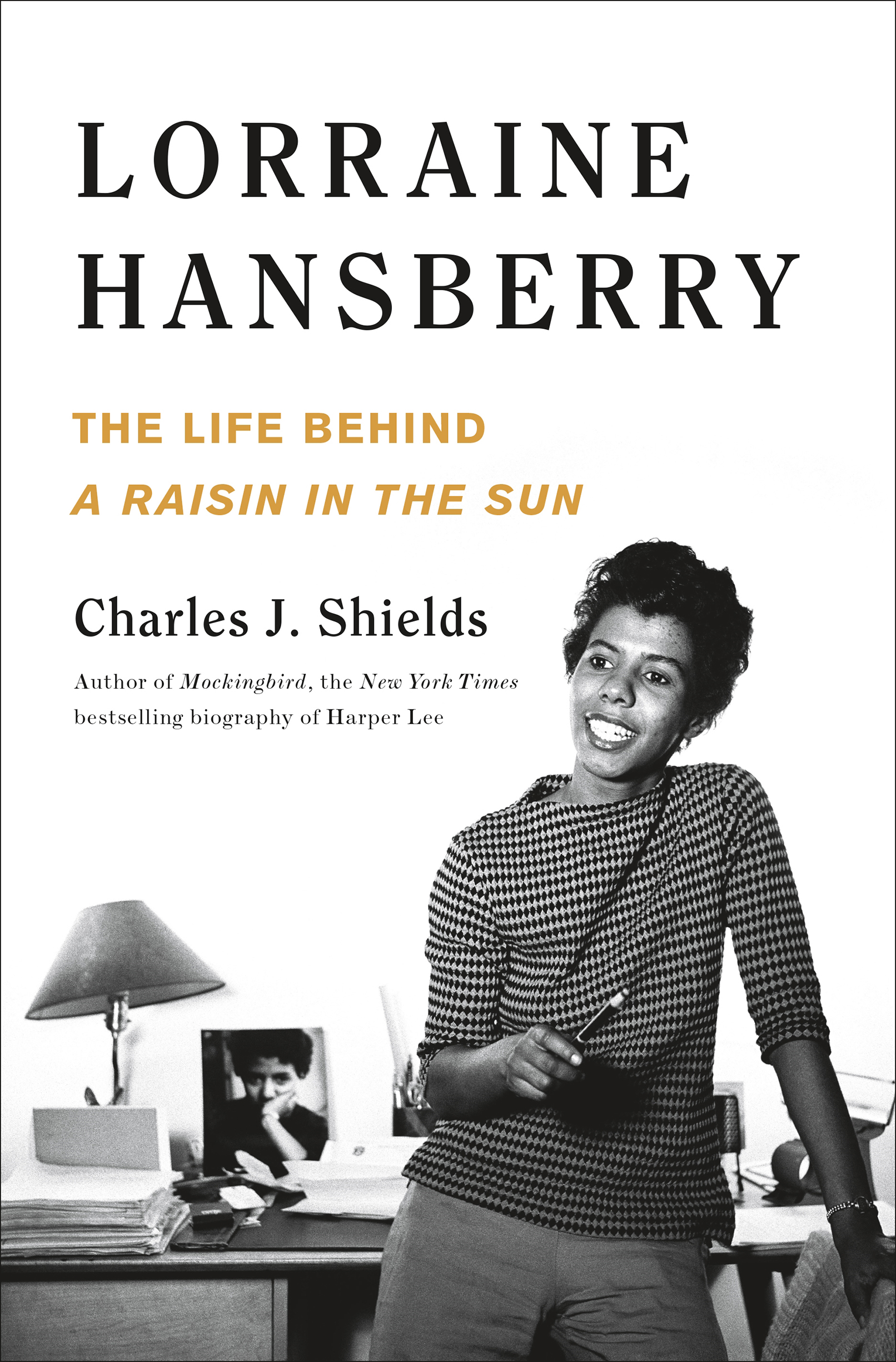

This book is about Lorraine Hansberry, an American playwright whose play A Raisin in the Sun competes with Arthur Millers Death of a Salesman for the honor of the most popular work of mid-twentieth-century American theater. No other play from that era is more widely anthologized, read, or performed than Hansberrys most famous work, written when she was just twenty-nine.

Until the curtain rose on A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, Never before, in the entire history of the American theater, had so much of the truth of black peoples lives been seen on the stage, James Baldwin wrote. During the decade that followed, more than six hundred black theater companies opened their doors, providing venues for works by Amiri Baraka, Ed Bullins, Alice Childress, Ntozake Shange, and August Wilsonthe high-water mark of twentieth-century African American drama. Had Hansberry not died at thirty-four in 1965, today she would have been an elder spokesperson in the LGBTQ and Black Lives Matter movements. Her ability to articulate and dramatize human rights would have brought her to the forefront of current thought and literature.

This biography is an attempt to situate Lorraine Hansberry with her contemporariesmidcentury American writers, artists, and activists. My approach to writing a life is to focus on what sets a person apart from others, who influenced them, and which events became turning points in their lives. Fortunately, Hansberry had a gift, or maybe an instinct, for engaging with the leading black American playwrights, novelists, activists, and cultural leaders of her day. The richness of her private correspondence, her notes to herself, and drafts of unpublished workscurated for twenty-five years by her former husband, Robert Nemiroffopen a window onto how Hansberry saw the world. To show her development as an artist, I rely on her friendships, romances, ambition, and emotional struggles. She cultivated multidimensionality in her personal and professional life, which led to new directions in her work and love affairs.

A side of her that will be new to readers is her complicated loyalty to her family. She was raised upper-middle class, and despite being an anticapitalist, she enjoyed the cultural and material advantages of an upbringing among the black elite. She stood by her family as they fought to maintain a lifestyle that was built on a family dynasty of black free enterprise on Chicagos South Side.

Also presented here for the first time is a domestic portrait of Hansberry and Nemiroff, and of their creative partnership. The Nemiroffs of Greenwich Village is an unusual story.

A Note about Usage: Lorraine Hansberry was not interested in capitalizing the first letters of the expression black race, she said in 1959, any more than I could imagine that anyone should wish to suddenly start writing White Race. The reason was American Negroes take the view that we are a specific and not a generality. I accede to her preference and lowercase black and white throughout the book and rely on Negro now and then. Negro is quite as accurate, quite as old and quite as definite as any name of any great group of people, wrote W. E. B. Du Bois.

I went to Chicago as a migrant from Mississippi. And there in that great iron city, that impersonal, mechanical city, amid the steam, the smoke, the snowy winds, the blistering sun; there in that self-conscious city, that city so deadly dramatic and stimulating, we caught whispers of meanings that life could have