Contents

Guide

For her brilliance

INTRODUCTION

Lorraines Time

For some time nowI think since I was a childI have been possessed of the desire to put down the stuff of my life. That is a commonplace impulse, apparently, among persons of massive self-interest; sooner or later we all do it. And, I am quite certain, there is only one internal quarrel: how much of the truth to tell? How much, how much, how much! It is brutal in sober uncompromising moments, to reflect on the comedy of concern we all enact when it comes to our precious images!

Lorraine Hansberry

FOLLOWING HER LEAD , I too am putting down the stuff of Lorraine Hansberrys life. In my hands, the narrative comes from the sketches, snatches, and masterpieces she left behind; the scrawled-upon pages, published plays, and memories: her own and others from people who witnessed and marveled at, and even some of those who resented, her genius.

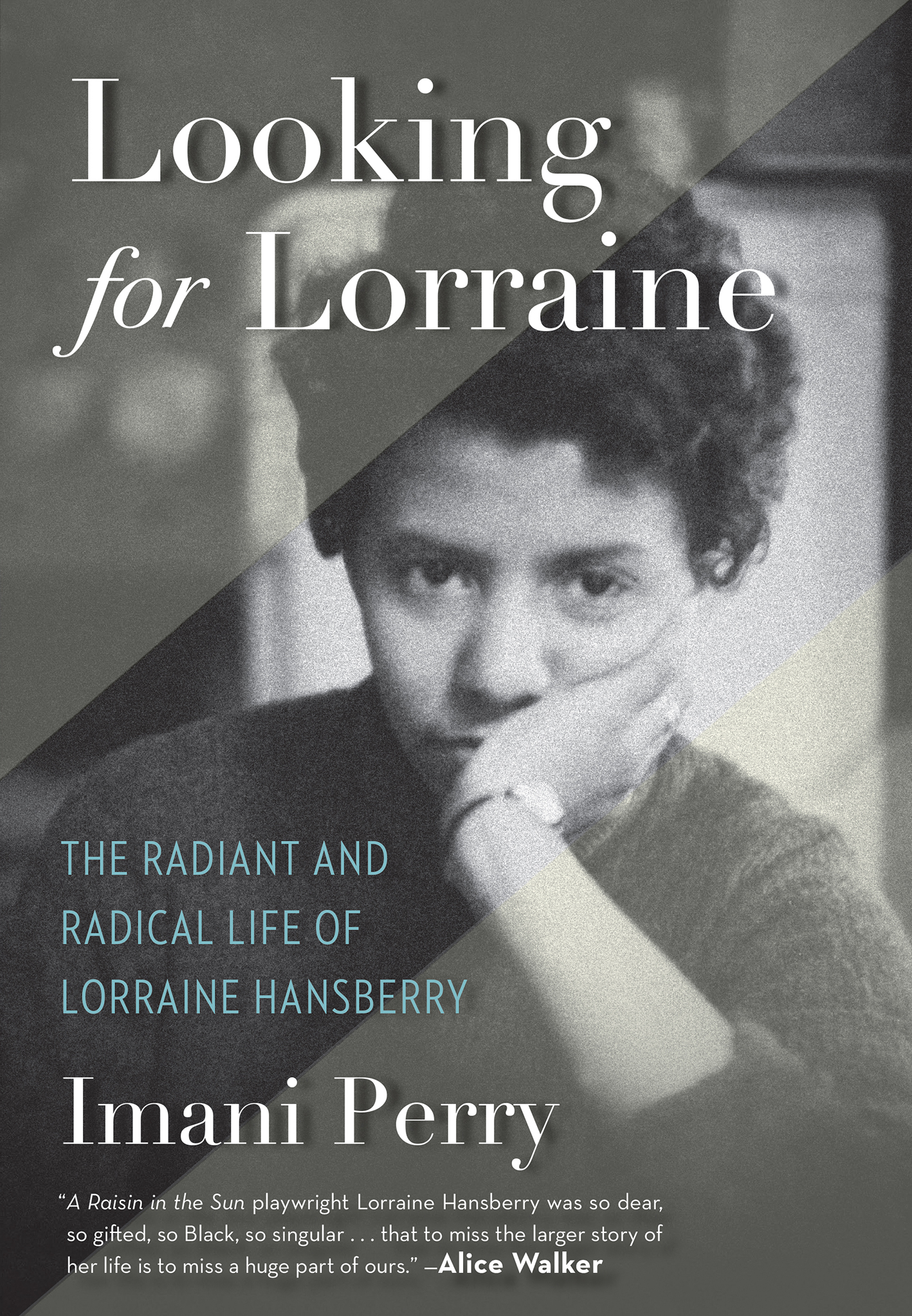

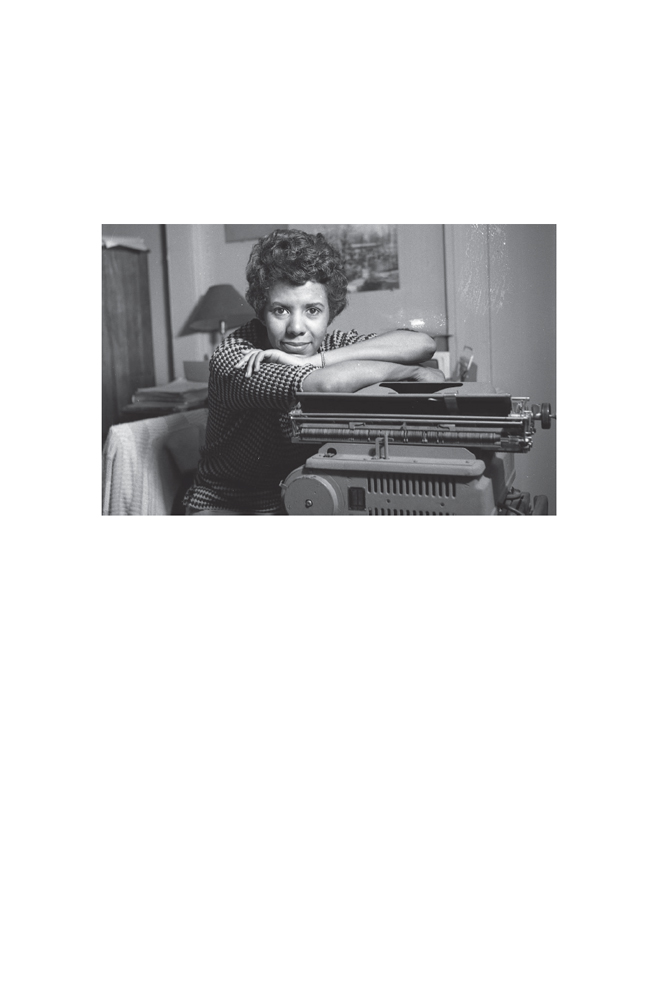

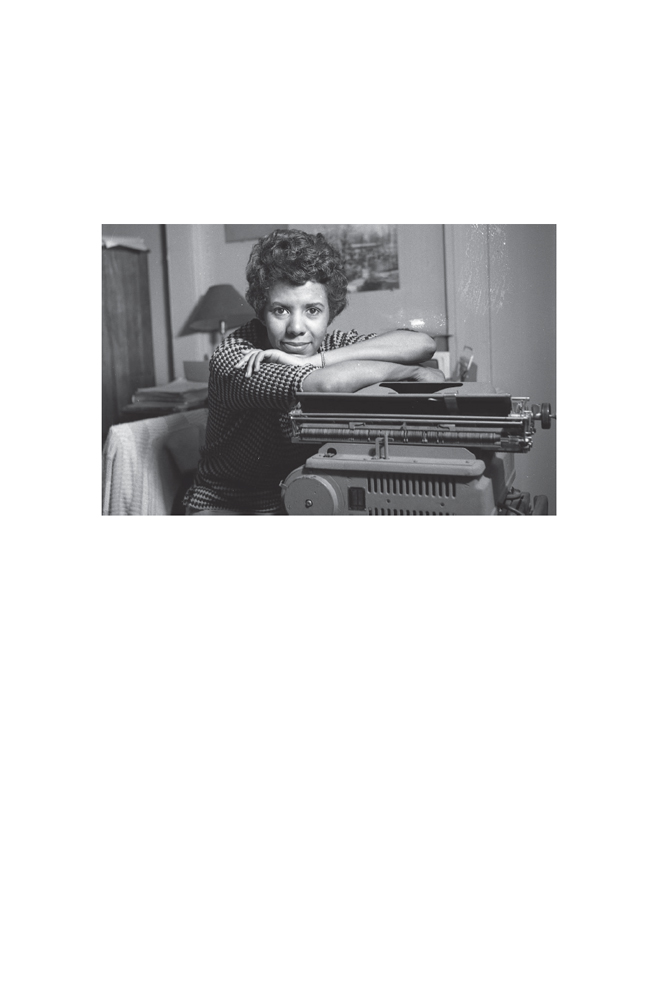

But why did I believe this book, less a biography than a genre yet to be namedmaybe third person memoirhad to be written? The obvious answer is Lorraine Hansberry was the first Black woman to have her play produced on Broadway and the first Black winner of the prestigious Drama Critics Circle Award. That first play, A Raisin in the Sun, is the most widely produced and read play by a Black American woman. It is canonical, not just in Black American literature but also in American arts and letters. She is an important writer. And Lorraine Hansberry is an important writer who has had far too little written about her, about her other work, about her life. Hers is a story that remains in the gaps despite the fact that she was widely influential. Her image in the public arena has a persistent flatness, even now as more people know about the details of her life. Knowing only two dimensions is our misfortune. She sparked and sparkled. Now, in the digital age, to so easily hear her voice, to look at the many photos that pop up on Google Images, to search newspaper archives for her incisive comments and her teasing wit is to feel the crackling excitement of her persona. Her eyes are alight. Her voice veers between the studied artifice of elocution and the drawled vowels and rhythm of the Chicago South Side to, finally, the slurring speech of the terminally ill. Elegance in one photo gives way to the boyish charm and mussed hair of another. It isnt hard to see there was a great deal of there there.

Lorraine died young. That is undoubtedly one reason we know too little. The life cut short has cast a pall over remembrance. The question What if she had lived? echoes. What else wasnt done? Poor remnants of an unfinished life lie dormant, at least that is what many critics have told us. And then there is the way the play itself, canonized neatly as the story of a Black family fighting Northern segregation, is set into the narrative drama of the twentieth century United States, the march toward freedom. Like Selma, like Washington, A Raisin in the Sun sits static.

Static things dont breathe. Or live.

But Lorraine did. Deeply.

I call her Lorraine rather than Hansberry because she is just one of a number of Hansberrys whose names you ought to know. I cant just call her Hansberrythe surname of her uncle, her mother, her father, her grandfatherbecause I might mean any one of those notable figures. In thirty-four years, the briefest life of the great Hansberrys, she left a lasting impression. She was an artist and an activist. She was strident and striking, an aesthete, and, as John Oliver Killens called her, a socialist with a black nationalist perspective. Born at the dawning of the Great Depression, she was one of those great artists whose life rode the wave of some of the most pivotal and complex moments in American history: World War II, McCarthyism, civil rights. Lorraine was right in the thick of it, trying to make sense of it all.

There are enticing details: She was a Black lesbian woman born into the established Black middle class who became a Greenwich Village bohemian leftist married to a man, a Jewish communist songwriter. She cast her lot with the working classes and became a wildly famous writer. She drank too much, died early of cancer, loved some wonderful women, and yet lived with an unrelenting loneliness. She was intoxicated by beauty and enraged by injustice. I could tell these stories as gossip. But I hope they will unfold here as something much more than that.

Legacies and traditions are funny matters. They are so often pruning devices. For example, to write about Lorraine is to write about the remarkable legacy of Chicago, and more broadly the Midwest, in the history of Black art in the United States. She followed in the footsteps of so many greats: Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Ralph Ellison. She set the stage for so many more, like August Wilson and Toni Morrison. When I say that, I imagine what comes to mind for some readers are those laminated posters of famous Black writers. This one might read Great Black writers of the Midwest and have elegant photos with their names written in cursive. But to write about Lorraine in the way I intend to here, and to think of her as part of the tradition, is not that kind of gig. Like the ones who came before, she lived an artists life, a flesh and blood life, with a great deal of difficulty and little in the way of respectability once she committed fully to who she was. She did things that were politically dangerous. She was brave and also fearful; experimental and superb. She failed and hurt. Her tradition, then, cannot be reduced to the picture of greatness. It has to entail the vagaries of imagination and the many circumstances that excite it.

By the mid-twentieth century, Chicago Black artists, working in the shadow of the University of Chicago, which had decades of studying poor Black people as one of its many validating archives, had been grappling with what could be called sociological conditions for a very long time. Poverty, racism, segregation, mob violence, overcrowding, so many people in such little spacefor Black Chicagoans these things existed amid factory smoke and meatpacking plants, entrails on the ground, and grime in the cracks. The exploration of big human questions about love and meaning always had material conditions as a backdrop. That was the Chicago tradition into which Lorraine was born. She too struggled over the social and political meanings of dreams and their deferral, rejecting absolute bleakness and anything too romantic or abstract. Instead, she looked for what was real about the human experience under captive conditions.

Lorraines searching was one for her own life and also for her art. She stood in the collective tradition of the Black artist, but also in a family tradition of the Black activist and public servant. Her fathers father, Elden Hansberry, was a history professor at Alcorn College. Her father, Carl, an Alcorn graduate, was a civil rights activist and a real estate entrepreneur. Her mother, Nannie, was a teacher and a ward leader. Her uncle William Leo Hansberry is known as the father of African Studies and worked as a professor at Howard University. She grew up surrounded by their interlocutors: lawyers, physicians, activists, intellectuals, businessmen. Their expectation was that all their children would grow up to do something of significance that would not just be a sign of personal excellence but also achievement for the race.