Contents

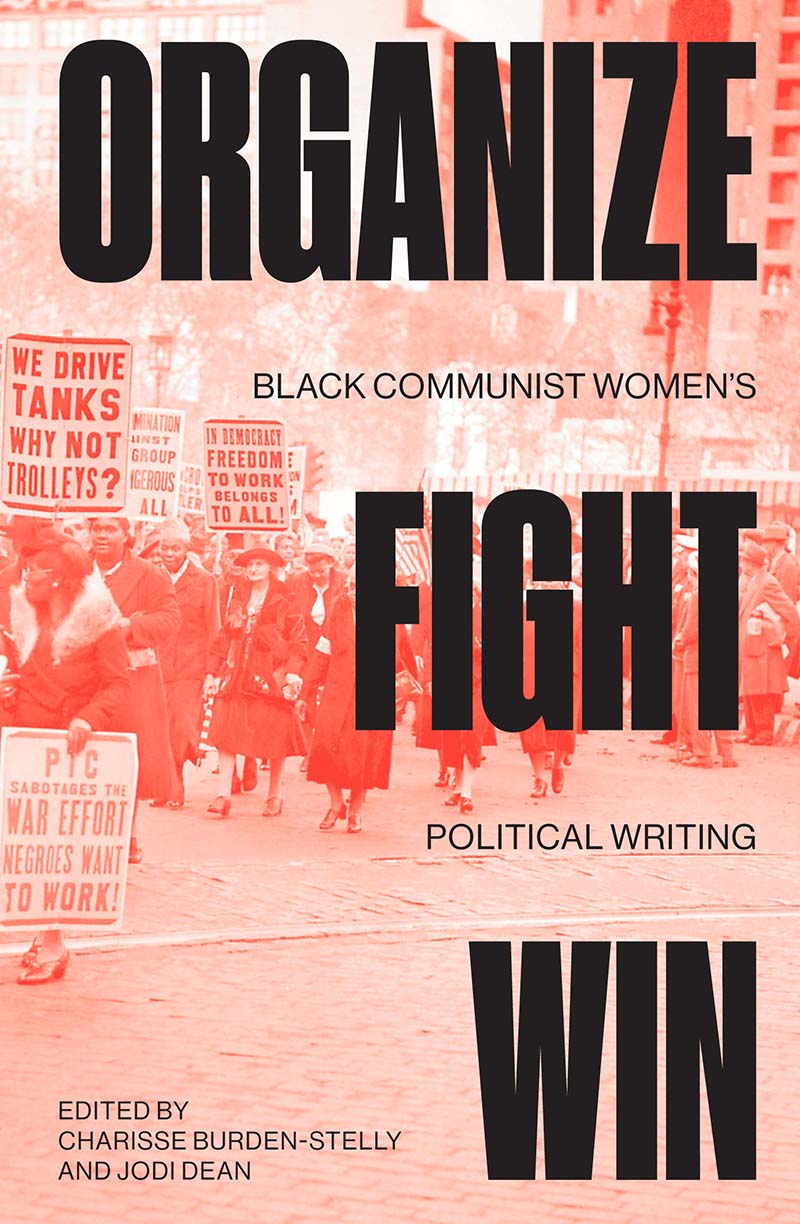

Organize, Fight, Win

Organize, Fight, Win

Black Communist Womens Political Writing

Edited by

Charisse Burden-Stelly and Jodi Dean

First published by Verso 2022

Collection Verso 2022

Contributions Contributors 2022

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the editor and authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11217

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-497-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-498-1 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-499-8 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Minion by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

Section I:

Struggle in the Early Years

Section II:

Organizing, Labor, and Militancy

Section III:

Fighting Fascism

Section IV:

Winning Peace at Home and Abroad

Section V:

The Struggle Continues: White Supremacy and Anticommunism

The bulk of the work of identifying, locating, compiling, and transcribing the contributions to this collection was carried out during the spring and summer of 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people provided generous assistance and support; the volume could not have existed without their work. We are especially grateful to Sadie Kenyon-Dean for transcribing each of the texts. We extend our thanks to Adam McNeil for his work securing permissions. We appreciate the Faculty Research Grant from Hobart and William Smith Colleges that let us pay Sadie and Adam for their work. Special thanks go to MaryLouise Patterson and to the Communist Party of the United States of America for publication permissions. Additional thanks go to Carrie E. Hintz and Rachel Detzler from the Rose Library at Emory University and Jennifer Nace from the Warren Hunting Smith Library at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. A number of scholars shared their invaluable time, expertise, and enthusiasm; we are especially grateful to Gregg Andrews, Melissa Ford, Erik Gellman, Sean Guillory, LaShawn Harris, Gerald Horne, Zifeng Liu, Erik McDuffie, Minkah Makalani, and John Munro. Finally, the book is also the product of the labor of the talented and committed workers at Verso, especially Rosie Warren, Jeanne Tao, and copy editor Steve Hiatt.

At the founding convention of the National Negro Labor Council on October 2728, 1951, Black Communist women received emphatic applause as they asserted their importance in and to the labor movement. Throughout the meeting, they emphasized that as long as Black women were locked out of significant sections of US industry, reduced to domestic service, and marginalized in or left out of unions, the labor struggle as a whole would be weakened. The refusal to fight against the abuse of domestic workers and to organize this section of oppressed laborers rendered the union movement incomplete at best. Women such as Helen Lunelly and Viola Brown pointed out that a key struggle of the Labor Council was to open the doors of factories and industry to Black women while simultaneously struggling for livable working conditions and wages for domestics. By offering this powerful critique, Black Communist women redefined who counted as a worker, shed light on the intersections of oppression and exploitation that needed to be addressed by the labor movement, and presented the necessary actions for launching a truly representative labor struggle.

This analysis did not originate after World War II. At the first meeting of the National Negro Congress (NNC) from February 14 to 18, 1936, Black Communist women helped to shape a resolution for a national movement, under the direction of the NNC, to organize domestic workers85 percent of whom were Black womento regularize their hours, raise their wages, and improve their living conditions. Such a movement would elevate the conditions of Black and working people as). Black womens plight was not only the plight of the Black community; it was the plight of all workers struggling against the intensification of subjection in the throes of the Great Depression.

This astute analysis of the structural and material conditions of Black women had been articulated even earlier by Grace Campbell, one of the first women to join the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). In 1928 Campbell wrote:

Negro women workers are the most abused, exploited and discriminated against of all American workers, not only by the capitalist system and the employers, but by unenlightened race prejudice which is found even in the working class, and is used by the employers to drive a wedge between the black and white workers and thus destroy their unity and fighting power.

Campbell was ahead of her time in using the realities of Black women workers to illuminate the importance of struggling against capitalism and racism simultaneously to shore up interracial worker unity. Black Communist women understood that satisfying the material needs of the most bitterly exploited group would strengthen the labor movement and its ability to struggle against class domination and its intensification by imperialism, war, racism, and fascism, which combined all of these. This was not least because, as Claudia Jones put it, Black women were the real active forcesthe organizers and the workers in the institutions and organizations that were central to the economic, political, and social life of Black people; addressing their special oppressed status would help to bring their militant energy to even greater heights in the fight for peace and socialism.

For several decades in the early to mid-twentieth-century United States, Black Communist women organized, fought, and led mass campaigns against national oppression and economic exploitation. Within and Engaged in international struggles against fascism and colonialism, they built new organizations and created an international movement for peace. Yet their work forging the CPUSA and envisioning an international socialism dedicated to Black liberationand Black liberation with socialism at the centerhas been largely excluded from popular visions of twentieth century radical left politics. This intellectual McCarthyism, or erasure, suppression, and forgetting of the contributions of these theorist-organizers, distorts our understanding of organized radical politics. In restoring the likes of Grace Campbell, Williana Burroughs, Maude White Katz, Thyra Edwards, Ella Baker, Marvel Cooke, Louise Thompson Patterson, Esther Cooper Jackson, Thelma Dale, Claudia Jones, Vicki Garvin, Dorothy Hunton, Lorraine Hansberry, Eslanda Goode Robeson, Dorothy Burnham, Yvonne Gregory, Charlotta Bass, and Alice Childress to their rightful place in radical left political history, this volume seeks to expand our understanding of what radical left movements have been, and what they can be.

Scholars such as Dayo F. Gore, LaShawn Harris, Gerald Horne, Robin D. G. Kelly, Lydia Lindsey, Minkah Makalani, John H. McClendon III, Erik S. McDuffie, Mark Naison, Mark Solomon, and Mary Helen Washington have done crucial work bringing to life the activist milieu of Black women in and around the Communist Party in the first half of the twentieth century. Likewise, Horne, Gregg Andrews, Carole Boyce Davies, Keith Gilyard, Imani Perry, Barbara Ransby, and Sara Rzeszutek, among others, have written indispensable biographies of Shirley Graham Du Bois, Thyra Edwards, Claudia Jones, Louise Thompson Patterson, Lorraine Hansberry, Eslanda Goode Robeson, and Esther Cooper Jackson, respectively, excavating how these women shaped and were shaped by the CPUSA.Political Writing builds on these scholarly contributions by compiling, for the first time, these womens political writing into a single volume. It aims to support and supplement the path-breaking research that has challenged liberal reductions of Black politics to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, other mainstream organizations, and the civil rights movement; left reductions of Communist politics to white male workers, industrial and trade unionism, and Cold War stereotypes of domination from Moscow; and feminist reductions of womens politics to white, bourgeois, idealist preoccupations with attitude, identity, and privilege. Black Communist women theorized capitalisms investment in dividing workers by race, sex, occupation, skill, and even region. They sought to build power through unity and unity through equality.