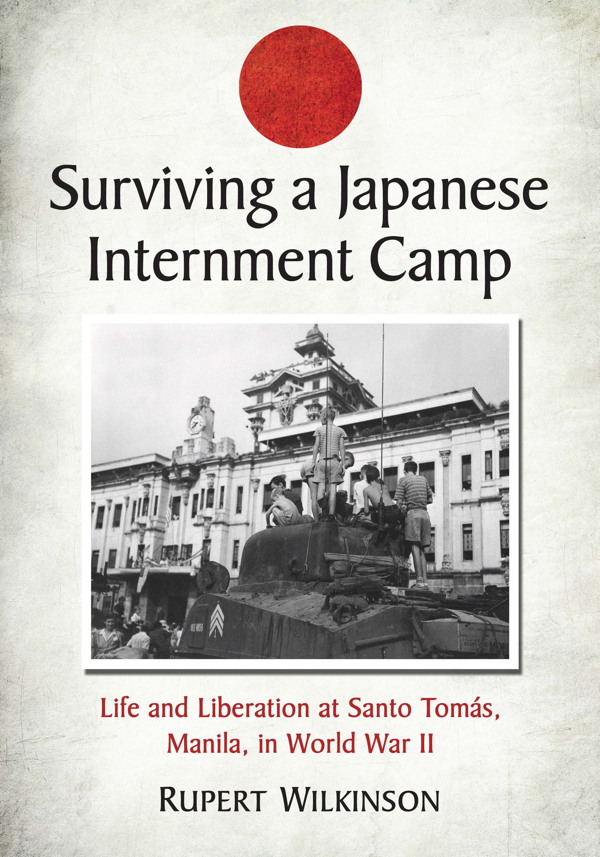

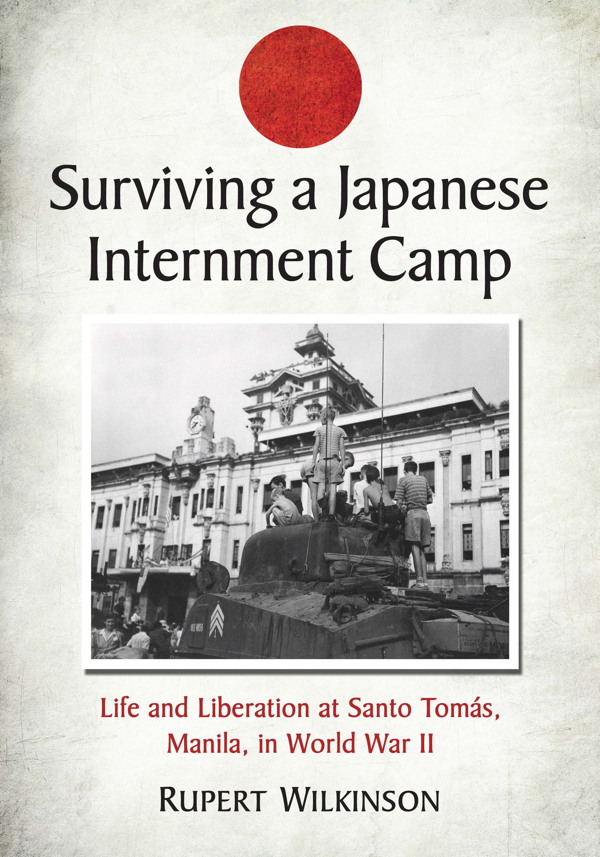

Surviving a Japanese Internment Camp

Life and Liberation at Santo Toms, Manila, in World War II

Rupert Wilkinson

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1218-8

2014 Rupert Wilkinson. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: Liberated internee boys on U.S. Army tank Ole Miss at Santo Toms, ca. February 5, 1945 (U.S. Signal Corps, courtesy of MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, Virginia)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Mary June, and the memory

of our mother, Lorna Wilkinson

Acknowledgments

Many of the informants who helped me with this book were fellow Santo Toms internees, though I dont expect them all to agree with all my judgments. In acknowledging interned women and girls whose surnames changed due to marriage, I give their camp family names before their married names.

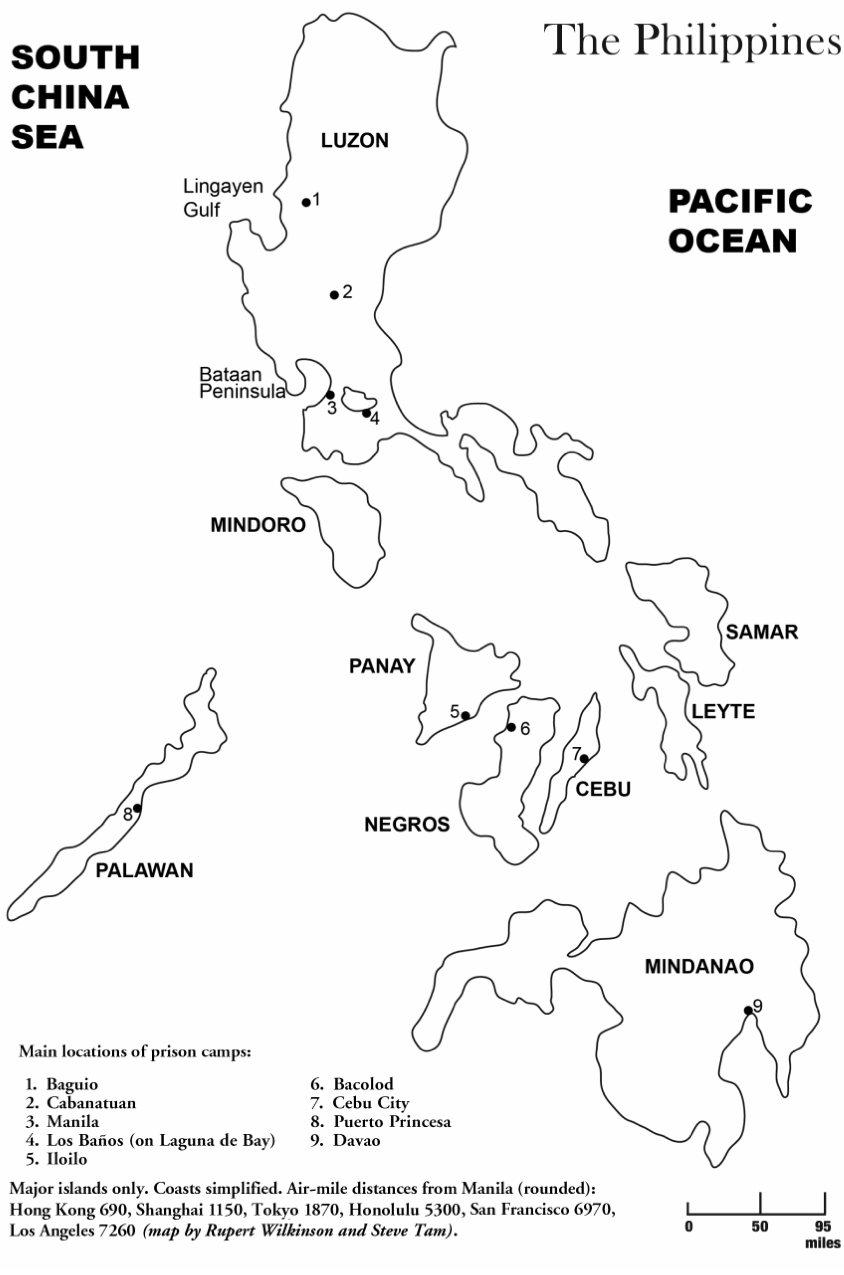

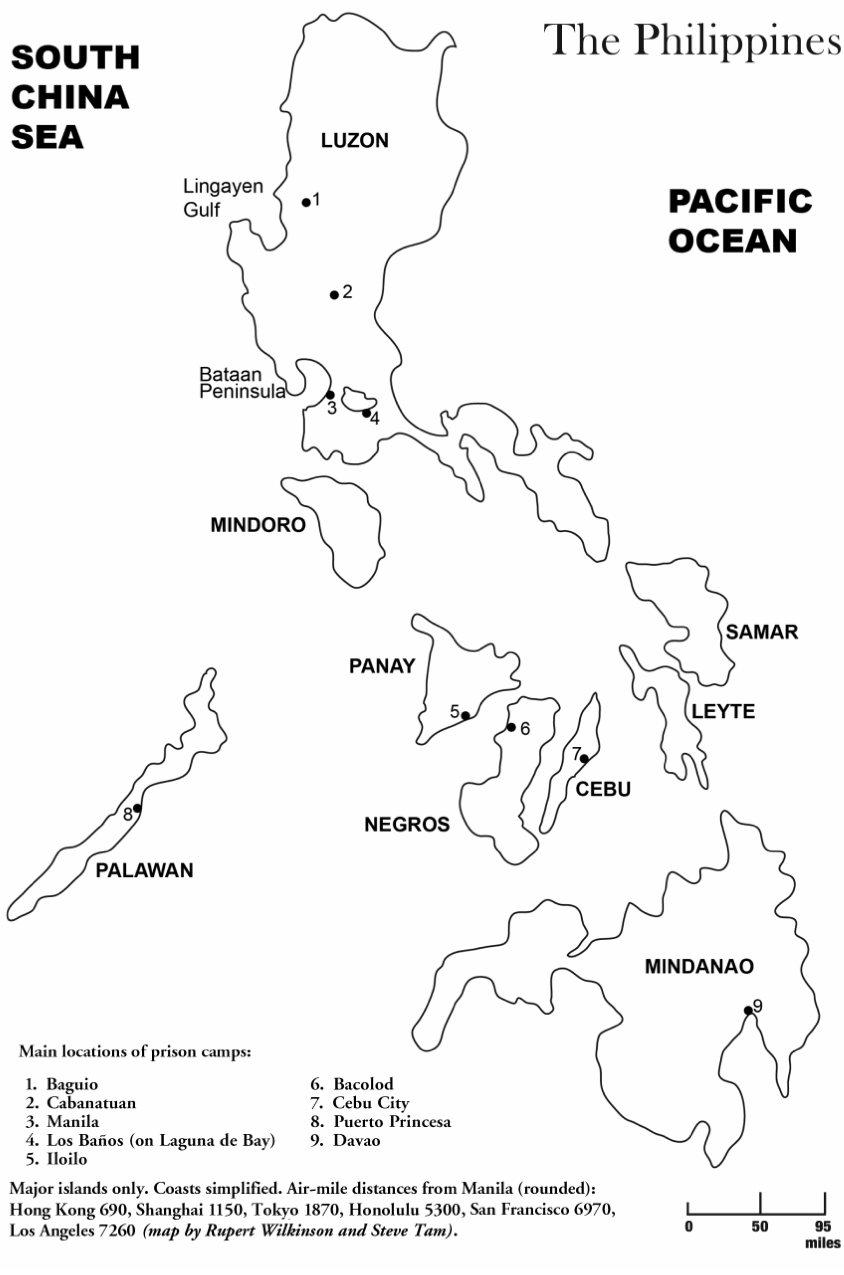

Among myriad creditors, some warrant special mention. My wife Mary Wilkinson spent hours and hours rigorously editing all chapters, prompting rewrites, advising on pictures, finding gems alongside me in the U.S. National Archives, and listening ad nauseam to camp stories. My sister, Mary June Wilkinson Pettyfer, and camp chum, Nicholas Balfour, vividly improved on my own memories, both being older than me. Mary June read draft chapters and made valuable and supportive suggestions; so did my daughter, Camilla Wilkinson. Roderick Hall, whose master bibliography of the wartime Philippines is a memorial to his Filipino family executed in Manila, gave me books, Manila contacts, information, and always encouragement. Curtis Brooks, Liz Lautzenhiser Irvine, and Sascha Jean Weinzheimer Jansen, exceptionally informed ex-internees, provided huge amounts of information, supplemented by Curts military knowledge and by many documents from Liz as well as from Caroline Bailey Pratt and James Ward. Yukako Ibuki procured and translated the camp guards logbook and advised me on aspects of prewar and wartime Japan. Yolanda Cruz, Oberlin College biologist, gave me superb, instant tutorials on malnutrition, as well as stories and information from her Philippine past. Margaret Ball, daughter and granddaughter of camp internees, gave all kinds of help, including insights into Manila expat life. In Manila itself, Mary Junes son, Robin Pettyfer, a pioneer of videoconferences bridging different Philippine and Indonesian groups, explored the campsite when I could not get to it; he answered various what where questions from me, as well as sending me maps and photos. Back here, Adam Thorpe gave generous time and skill, scanning and adjusting the illustrations.

Long before any of this occurred, two people grandmothered the book more than they may realize: daughter Clara Klat, by getting me to write an informal memoir, and then Penny Curtis Mellor, another internees daughter, by suggesting I read more books on the camp to give my account fuller background. Only then did I think of writing a full history of the camp, with some personal basis but more than a memoir.

The chapter on the camps rescue needs a special mention. It is the first time I have written military history and I wonder if any military historian ever gets everything right, such is the fog of war. In trying to be as accurate as possible while bringing the event alive, I am indebted to Richard Seron, longtime researcher on the subject, and his associate, Lt. Col. Walter Landry (1st Cavalry Division), one of the first American soldiers into Santo Toms; he was awarded a Silver Star. Both responded generously to shoals of questions from me about the three days in February 1945 when the flying columns fought to free the camp. Throughout the books writing, Richard and I discussed many aspects of the camps liberation; we used hours of taped testimony by Walter Landry, plus crucial information from Susan Trout, daughter of a flying-column veteran, and interviews with a few surviving liberators (in the list below with their units). Had I relied solely on army-unit reports and published accounts, important aspects of the rescue might have been lost to history.

At library archives, more than routine help came from Eric Vanslander (U.S. National Archives), James Zobel (MacArthur Memorial Library), Suzanne Yupangco and colleagues (Filipinas Heritage Museum, Manila), Naoki Kanno and Satoko Mikado (National Institute for Defense Studies, Tokyo), and Roger Suddaby (Imperial War Museum, London).

I wish I could describe the help given by others; they are too many for that but I do want to name them. I thank Anthony de Alcuaz, Mark Allen, Len Baker, Frederico Baldassarre, Sebastian Balfour, Tika Balfour, May Berenbaum, Lynn Bloom, William Boudreau, Andrew Bridgeford, Dorothy Mullaney Brooks, Mike Browning, Ted Cadwallader, Alexander Calhoun Jr., Craig Comstock, Jay Crawford, Hazel Templer Cripps, Tom Crosby, Keith Cunliffe, Wanda Werff Damberg, Bill Davidson, Patrick Di Matteo (1st Cavalry Division), Roy Doolan Jr., Susan Douglas, Betsy Enriquez, Lettye Staight Falk, George Fisher (44th Tank Battalion), Maurice Francis, Sonia Francisco, Cornelia Lichauco Fung, Susan Go, Lou Gopal, Juergen Goldhagen, Malcolm Green, John Hawkins, Irene Duckworth Hecht, Jeremy Herklotz, Don Hossler, Michael Hurst, Addie Gibb Jensen, Ricardo Jos, Marie Kish, Iris Krass, Edgar Krohn, Jenny Templer Kyle, Ric Laurence, Benito Legarda, Jr., Karen Kerns Lewis, Barbara Linder, Cortland Linder, Cecily Mattocks Marshall, Edward McCreary, Jr., Connie Hall McHugh, Robert McWilliam (5th Field Hospital), Martin Meadows, Frank Mendez (1st Cavalry Division), Chelly Mendoza (1st Cavalry Division), Alberto Montillo, Leslie Murray, Hitoshi Nagai, James Nelson, Elizabeth Norman, Maita Oebanda, Walter Olson (37th Infantry Division), Peter Parsons, Carol Petillo, Geege Wootten Poston, Ben Richardson, Juan Rocha, Florentino Rodao, Roger Schade, Margo Tonkin Shiels, Jeanne Siegel, Michael Snape, Don Stevenson, Charles Sullivan, Ralph Thompson, Bill Tonkin, Albert Walters, Richard Walters, Terry Wadsworth Warne, and Peter Wrinch.

Not all of these people are still alive. I regret that I started serious work on the camps history more than a decade after my mother, Lorna Wilkinson, died in 1992. Now and then she mentioned camp experiences, some of which she recounted to Trish Marx for her childrens book Echoes of World War II (1989) on six wartime children including me (my own comments there are not all correct). But how much more would I have learned had I questioned her systematically? One compensation is that by waiting so long I could use a new generation of memoirs and diaries, some edited by the children and even grandchildren of internees.

Introduction: Telling the Santo Toms Story

Manila, 3 February 1945. It was after nightfall when six U.S. Army Sherman tanks with an assortment of jeeps and trucks trundled into Calle Espaa, the street running past the main gate of the old Dominican University of Santo Toms. They waited there while more trucks came up. The force numbered 200 GIs, led by a lieutenant colonel, Haskett (Hack) Conner. They were the frontrunners of a flying column of tanks and motorized infantryreally a series of small detachmentscutting through the Japanese lines to liberate Santo Toms Internment Camp, the university turned prison for nearly 4,000 Allied nationals.

Next page