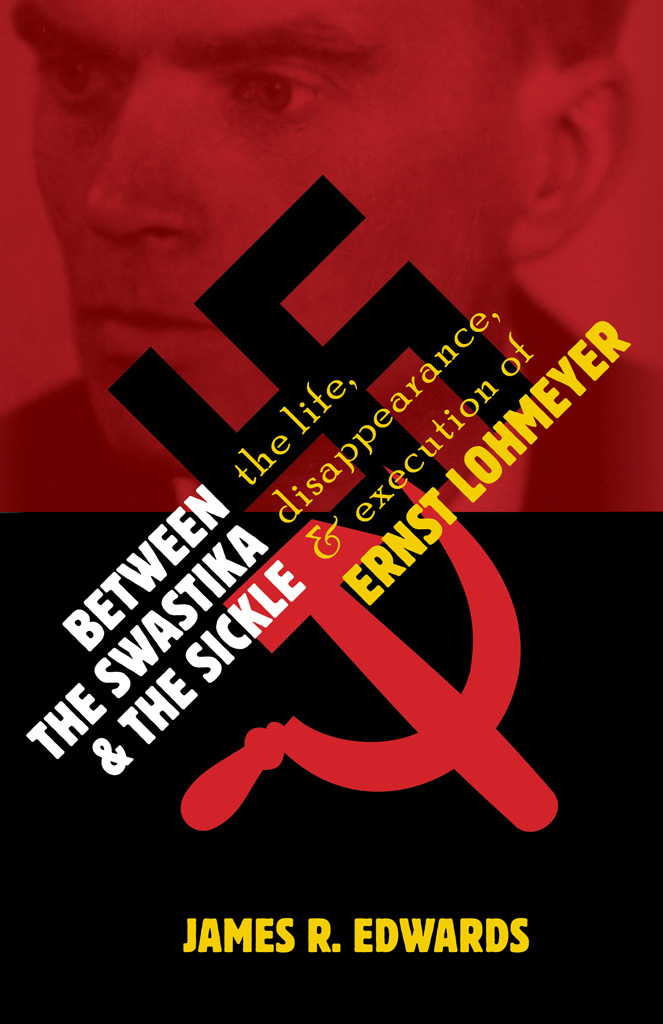

Between the Swastika and the Sickle

The Life, Disappearance, and Execution of Ernst Lohmeyer

James R. Edwards

WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY

GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

4035 Park East Court SE, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546

www.eerdmans.com

2019 James R. Edwards

All rights reserved

Published 2019

252423222120191234567

ISBN 978-0-8028-7618-8

eISBN 978-1-4674-5661-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

To Melie Seyberth Lohmeyer,

beloved wife of Ernst Lohmeyer,

who championed his life

and preserved his memory

Contents

In 1996 I published an article on the mysterious disappearance and death of Ernst Lohmeyer that appeared just weeks before the fiftieth anniversary of Lohmeyers execution, which was commemorated at the University of Greifswald on September 19, 1996. I assumed that the publication of this article would be my only contribution, major or minor, to Lohmeyer scholarship. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent demise of communism, sources related to the life and death of Ernst Lohmeyer that I had pursued in a clandestine manner in East Germany were finally open to all, and it seemed proper to me for Germans themselves to air the story of this remarkable scholar and witness of faith and character. For the next twenty years I transitioned from sometime East German sleuth back to other roles related more directly to my discipline as a professor of New Testament. Lohmeyer himself remained a fixed feature of my mental world, of course, but I had no plans of developing that feature beyond the scope of the 1996 article I had written.

When I retired from full-time teaching in 2015, two things caused me to change my mind and plunge into a full biography of Ernst Lohmeyer. One was that by 2015 Gudrun and Klaus Otto, Lohmeyers daughter and son-in-law, had died, as had Professor Gnter Haufe, Lohmeyers successor as chair of New Testament at the University of Greifswald. Gudrun, Klaus, and Gnter had been my three best informants on Lohmeyers life and fate. Indeed, they were genuine mentors. Their deaths left my unlikely American voice one of the few remaining to tell the Lohmeyer story within the context of those who had preserved his memory during the attempted blackout of his name in communist East Germany.

A second awareness, closely related to the above, was perhaps even more compelling in changing my mind. As I mention more than once in the book, the Soviets did not simply kill Ernst Lohmeyer, they sought to expunge all memory of him, as though he never existed. Gudrun had reminded me that death is inevitable, but deprivation of honor is not. The first must be accepted, but the second need notor perhaps better, should notbe accepted. It became increasingly clear to me that not to tell Lohmeyers story was to abet, albeit it unwillingly, the expunging of his memory. At various points in Lohmeyers biography I relate my personal endowments that linked me to similar endowments of Lohmeyer. The determination of the Soviets to expunge his memory seemed to mandate marshaling those endowments to tell a story that deserved to be told but that otherwise might not be told. This latter realization became a virtual call, a necessary counteroffensive to reverse a mendacious victory of those committed to expunging Lohmeyers memory. Gudrun noted how her father made a rule not to refuse when asked for help that he could render. My situation conformed too closely to Lohmeyers paradigm not to apply it to myself.

The theological faculty at the University of Greifswald, thankfully, continues to keep the candle of Lohmeyers memory burning. A current member of the faculty there has written his doctoral dissertation on Lohmeyer, and a small but steady stream of academic work and conferencesone of which I note at the beginning of chapter 17continues to explore Lohmeyers significance as a theologian. A particularly pleasing example of this revival is the naming of the new residence of the theological faculty at Greifswald the Ernst Lohmeyer House. The plaque prepared for Lohmeyers exoneration on the fiftieth anniversary of his execution on September 19, 1996, now adorns the entryway of the Lohmeyer House, which lies directly across the green from the main hall of the university.

Virtually all resources I used in writing this book, whether written or oral, were German. This was inevitable, for Ernst Lohmeyer was German through and through, and he lived and wrote in an era when far fewer German works were translated into English than is true today. Apart from rare instances of English translations of Lohmeyers works, all English translations of German in this book are, by necessity, my own. For those who are interested, I have provided all German originalswhether individual words or entire paragraphsin the endnotes of each chapter. Readers with even minimal German proficiency will profit from reading Lohmeyers lucid, strong, and penetrating German. Within the biography I occasionally place in quotation marks conversations for which I do not provide the original German in endnotes. Most of these conversations are the result of my recall. I make no claim for verbatim accuracy in such conversations, but I wish to assure readers of the veracity of the sense of the conversations, if not of their exact words. In many instances my recall has been aided by written diaries that I kept in my various peregrinations in Germany. I did not keep written diaries while on Berlin Fellowship (an organization I shall introduce in the story) in East Germany for fear of their being confiscated at border crossings, thereby compromising our German friends in the East. I did, however, commit my itineraries, experiences, and key conversations there to personal diaries after returning to West Germany. The several conversations in chapters 1516 transpired after the fall of the Wall, and the time lag between event and transcription was reduced to no more than a day, and often to a few hours.

One of the most personally gratifying aspects for me in the Lohmeyer pursuit has been the interplay between the living and the dead, the church militant and the church victorious. That interplay has included voices on both sides of the Atlantic. As noted throughout this book, many Germans have contributed to the Lohmeyer legacy. The foremost among them have been mentioned in the book, especially Gudrun and Klaus Otto and Gnter Haufe. I am also indebted to Andreas Khns biography of Ernst Lohmeyer as a New Testament scholar, and his publication of Lohmeyers sermons as president of the University of Breslau. But there are others standing in the wings to whom I am also indebted. Ted Schapp, a West Berlin pastor, and Brbel Eccardt, a West Berlin catechist responsible for East work with Berlin Fellowship, both now deceased, nurtured and advanced my understanding of the church in East Germany for more than two decades. Their counterparts in the East, Gerhard Lerchner (2018), a pastor in East Germany, and Gerlinde Haker, a catechist at the Lutheran cathedral in the city of Schwerin, both of whom I met through Berlin Fellowship, possessed the rare virtue of demonstrating staunch resistance to oppression yet without vilifying oppressors. Both witnessed to the gospel of reconciliation in a dehumanizing world of East German socialism.

Names associated more directly with the writing of this book are Barbara Peters, who offered prompt and professional assistance to my various requests during her three-decade tenure in the archive of the University of Greifswald. Similar assistance from Dr. Ingeborg Schnelling-Reinicke at the Secret Prussian Archive in Dahlem, though of shorter duration, has been equally helpful in securing access to materials crucial to this book. I wish to thank Professor Dr. Christfried Bttrich, who now occupies the chair of New Testament at the University of Greifswald once occupied by Lohmeyer, for his invitation to lecture at a Lohmeyer Symposium in October 2016, and for his expressed advocacy of this book. I am further grateful to both Ingeborg and Christfried for their willingness to read the entire English draft of this book and offer many helpful suggestions for its improvement. Finally, I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Julia Otto and Stefan Rettner, grandchildren of Ernst and Melie Lohmeyer, for their continuation of the charitable legacy of their parents Gudrun and Klaus in support of my research into their grandfather, and especially for making all the photographs in this book available for publication.