Foreword

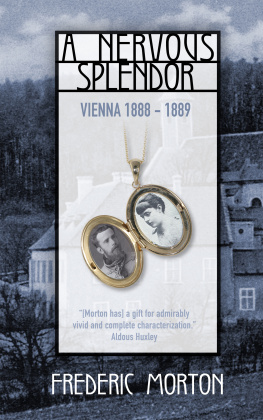

This book aims to tell a tale from history: the history of a community bound together by fate, comprising approximately 1,500 to 2,000 people ranging from His Majesty by the Grace of God all the way down to the lowliest servant, which was unique in European tradition. During my work in the archives, which form the basis of all historic research, the question of how was the unflagging point of departure and remained the guideline throughout the writing: How did people actually live inside the walls of the Viennese court? What was expected of them? How was the overall enterprise organised and managed (which nowadays would be considered a corporation)? How was this oldest of all European courts financed?

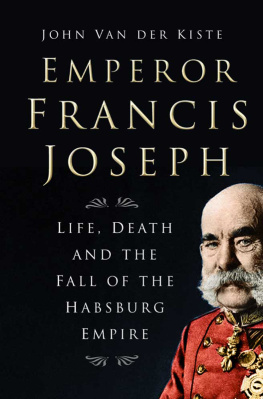

Today, no one knows much of anything about the court under Emperor Francis Joseph, its structure, its daily agendas and processes, or about the human beings who lived and worked with the emperor and were the closest witnesses of the longest reigning emperor in the history of Austria. It sometimes seems as if there were nothing which could still be told about the smallest city inside the capital of the empire and imperial residence of Vienna. No memoirs were left behind, neither by members of the imperial family, nor by employees; there exist no photographs portraying daily life at court. And most of all, the oral tradition of handing down knowledge and experiences the only thing which made it possible to run a court to begin with completely disappeared after 1918. Centuries of familiarity with the processes and organisation of a court, passed down from generation to generation, sank together with the monarchy itself into oblivion. Those people who were born into the court or learned their trade or profession under its aegis would have been able to tell elaborate tales, but were never asked; and in the 21st century, they are long dead.

At the Vienna Archives, however, the historical memory of the court and its inhabitants yet dwells, its heart still beats. Distributed through more than three and a half thousand cartons, not only the entire history of the imperial court under Francis Joseph slumbers, from the files of the chancellery to the protocols of the ceremonies, but also the stories of the human beings who form part of the overall complex. Each single file, as dry as it might appear at first glance, the greater part of them opened by the author for the first time since the monarchy came to an end, tells its own little story: about highly proper court officials who recorded the file to begin with; about the wheels of court administration; about the problems of communication; about awards and warnings from higher echelons. Yet the files also include touching personal details, revealing the worries and problems of people in a long past epoch: requests and petitions to the emperor for help in emergencies, hopes and concerns in providing for children at court, ambitions to be promoted or make a career at court. Even the downfall of the court, the dissolution of a 600-year old institution and the termination of an unspoken yet omnipresent pact between the ruler and his household community was recorded in minute detail and displays upon examination how those people who lived in the immediate vicinity of the emperor experienced the change of governmental systems.

Significant source materials bearing witness to the era have also survived in a variety of private archives. In stark contrast to the prosaic, dry files of court, views of court life from an utterly personal perspective through the eyes of those who worked and lived with and around the emperor, often in positions of high authority, are provided from such sources.

Only by combining and connecting the court sources of the administration and the personal memoirs of contemporaries of the emperor does it become possible to put together a comprehensive, multi-faceted and complete picture of life at the imperial court.

A closer look at the court also brings to light hidden aspects of the historic personality of Emperor Francis Joseph, providing a number of surprising discoveries. How did the emperor deal with the weakest links of the human chain at court? What was his view of the cultural responsibilities of the court? What did he expect of the uppermost ranks of court society, the elite? How did he navigate the court household through the turbulent and volatile periods of a regency which lasted 68 years?

A scientific, historic investigation of the relationship between emperor and court unveils a completely different picture of Emperor Francis Joseph, far different from the uncontested cliches depicting a stubborn and rigid ruler. It reveals how Francis Joseph reacted to political and social cataclysms, what novel strategies a ruler had to devise to navigate the transition of Austria from an absolutist state to a constitutional one, what instruments of power were torn from his hands and what techniques he devised to replace them; as well as the difficulties which arose when a ruler who embodied tradition and continuity was suddenly thrust into a new era in political, social and personal ways.

Last but not least, this history of the court of Emperor Francis Joseph, written just under one hundred years after the end of the monarchy, also provides the launch of a re-evaluation of Austrias longest serving ruler himself.

Vienna, October 2008

I A Day in the Life of the Old Emperor

Emperor Francis Joseph was awakened by his First Valet every morning at 3:30 am. Following his morning prayers, a rubber bathtub was dragged into the room and His Majestys First Bath Attendant tauntingly called Washcloth by the courtiers began his daily period of service. His undemanding duties consisted of soaping up the emperor and rinsing him off. His task was made more difficult by the fact that he invariably came to work inebriated. Often reprimanded by his superior, Washcloth invariably protested that he was the victim of his early hour of service. He had to start the day so early that he couldnt get out of bed; so he simply didnt go to bed, and stayed up all night at a local inn. And in order to keep awake until 3:30, he treated himself to a glass or two of wine. That was the sole cause for his staggering to work each day, redolent with alcohol, to perform his duties.

The emperor was always lenient with Washcloth. Occasionally, Francis Joseph remarked that the bath attendant really did reek of alcohol, but was always reluctant to fire him. It was not until Washcloth one time appeared for work so drunk that he couldnt even stand up straight, and had to hold himself upright by grabbing onto the neck and shoulders of the soaped-up emperor with all his strength to keep from toppling over, thereby nearly overturning emperor and bathtub alike, that the limits of patience were exceeded. The bath attendant had to be relieved of his arduous duties. However, he was not dismissed, merely transferred to a different court job which did not entail getting up so early in the morning.

The story of Emperor Francis Joseph and his bath attendant is symptomatic of the relations between the emperor and those in his employ at court. Francis Joseph was indulgent, he shied away from harsh penalties and above all refused to dismiss servants, much to the despair of his leading officials. He lived utterly in the aura and unspoken terms of patriarchal traditions of providing for those beneath him, seeing himself as father of his court servants. They were his children whom he had to take care of. They were not to be dismissed, even if they performed their duties poorly.

After his bath, valet Eugen Ketterl helped the emperor put on his uniform. Then followed breakfast: the identical breakfast served to officials and servants was brought to him at his desk. Apart from coffee and milk, he had breakfast rolls, butter and ham. And in the meantime, the court slowly lumbered to life. By 5:00 am at latest, a buzz of activity filled the halls of the court of Vienna. The first coaches delivered firewood, groceries and stationery needs for the officials. The wood carriers wheezed beneath the burdens of their bundles, trudging up and down every staircase of the Hofburg to supply each living and working section with the requisite fuel to last through the day. The cleaning staff ran back and forth across the inner yard carrying buckets full of water to commence the daily cleaning labours. In the court kitchen, more than 500 breakfasts were prepared, since only those servants who began their period of duty at 4:30 am had already had breakfast. The huge ovens in the court kitchen were fired up and the kitchen staff began to wash, scrub and slice the ingredients for the days pre-planned menu. As on every other day, hundreds of breakfasts, lunches and suppers had to be prepared. Throngs of livery servants, doormen and chamber servants scampered across the inner courtyards to their respective places of work, while night watchmen and supervisory staff retired to their rooms after a long night of service to finally rest their weary heads.