- 1 -

Bauang to Baguio

THERE WERE reeds on the river bank under the railroad bridge. The stream meandered lazily here and its waters were deep blue and almost still. Beyond on the opposite bank was a thatched roof under the shade of a tall banana tree whose large leaves waved in the soft breeze. The river disappeared at a nearby bend where a huge mango tree stood, each leaf reflecting the strong tropical sun.

It was much like a country scene in the summer in Japan. The difference was that we seldom take a bath in a river like this in Japan, and here I was busily scrubbing away.

Japan was far to the north, at an unbearable distance, one so great that I could not tell my family I was safe and sound in the small town of Bauang on the Gulf of Lingayen, La Union; safe from the savage battles on Leyte and from the air raids on Manila. It was a cruel distance that a harsh defeat had hopelessly increased.

A small fish flashed past me in the water. As I watched it dart away, I thought, "What price your life, little fish? What price mine?"

Kenzo Oda, a colleague of mine, came down the bank singing "The Song of Paratroops" in a strong baritone, and took off his clothes. The hair on his chest quivered in the breeze and beads of sweat glistened through it.

"They're not likely to come, are they?" I asked.

"Hardly likely," he said, stepping into the cool water. We were referring to the machine-tools that were to be brought to this town from Manila by train. It was our mission to receive the tools and carry them in trucks to Baguio, where Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita had his headquarters for the purpose of the protracted stand which he had planned.

"They say this place is the most likely spot for an enemy landing," I said.

"There's a rumor to that effect," he said indifferently. "In that case we'll have to retreat to Baguio, and even that place won't last very long."

Leaving my friend still singing "Paratroops," I went up onto the bank, dried myself and dressed. I nodded casually as I passed the garrison where sunburnt soldiers sat guarding the bridge, and entered the plaza in front of the church, an old stone one built in the Spanish era. The steeple was shining in the westering sun.

Here the highway forked to the north to San Fernando and to the east to Baguio. My billet, a house owned by a handsome Filipino couple with whom we lived, was near the corner. I went upstairs to my room and crawled into bed, pulled down the mosquito net and closed my eyes. I knew I should not be despondent about my family, my life and my fate; it was no use worrying about the future. I began reading Japanese haiku poems I had brought from Manila. Each verse was linked in meaning with the one preceding it and also with the one following. The scenes unfolded were those of the countryside of Japan in the good old days some two hundred years ago. When you are shut up in a room surrounded by the iron walls of fate, distance and military regulations, the only freedom you get is that of dreaming. This collection of short verses provided me with moments of happy reverie and repose.

* * *

I was not a soldier but a civilian teacher, attached to the Army to assist in education and information in the areas occupied by the Japanese. I had been teaching in Manila for the past two years, but now I was a transport agent with two trucks under my command.

In the earlier period of the occupation, our job went pretty smoothly; the Filipinos were cooperative. However, as the Americans took the Solomon Islands, landed on New Guinea, and occupied the small island bases in the Pacific, the people of the Philippines began to turn their backs on us and to look forward to the return of their former rulers.

Burma and Indonesia regarded the Japanese as their liberators-the natives had not liked their white rulers. The Philippines, however, had been satisfied with American democracy and the civilization which huge American capital had introduced. The Japanese invasion was a liability to the Filipinos, who soon found that the newcomer, instead of giving anything that corresponded to the Spaniards' religion or American civilization, was all for taking what little the people had or could produce. The prices of commodities soared. The issuing of more Japanese military scrip only increased inflation. Moreover, the islands in this republic were too numerous and personnel at the Japanese Army's disposal were too limited to police it properly. The forged scrip printed in the U.S., brought over in U.S. submarines, and smuggled into the country added to the difficulties.

The Japanese gospel of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and "the high spiritual culture of Asia" was only a joke to the Filipinos. The former was a-cover for Japan's despotic rule over the whole of Asia and the latter an excuse for poverty.

The Filipinos rose in revolt everywhere, and both Filipinos and Japanese were killed. Many innocent citizens were victims, just as in Vietnam today.

The teaching of Nippongo (the Japanese language) declined to such an extent that after the first American air raid on Manila on September 21, 1944, all the classes were virtually closed except the one at the University of the Philippines, where I taught a mere handful of students.

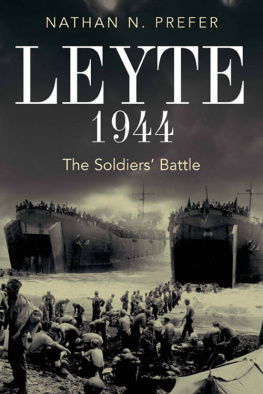

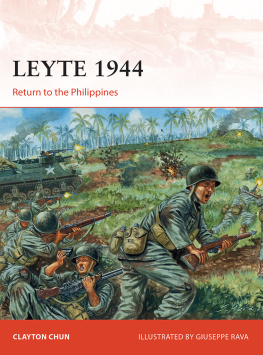

Meanwhile, the battles on Leyte ended in the most disastrous defeat in the history of Japan; with the loss of 80,000 soldiers, 1,000 planes, and more than 20 warships including the Musashi, one of the world's two biggest battleships. (The other was the Yamato, about the same size, which was also sunk six months later.)

Gen. Yamashita, commander-in-chief of the 14th Area Army, had given up all hope of staging a decisive battle and was determined to hold out in a protracted action so as to entice the enemy to the island of Luzon, thus preventing them from invading Japan proper before the Japanese at home were prepared for a showdown.

As the region for this prolonged resistance he chose the mountainous areas of Northern Luzon and established his headquarters in Baguio, the famous mountain resort. The food for his Army was to be obtained from the Cagayan Valley where there was an abundant rice crop.

There was much to be done in a hurry. The defenses had to be set up before the enemy landed. A great number of soldiers and civilians began to move north, and finally, on December 17, I was ordered to proceed north to this town on the mission already referred to.

One evening I called at a Filipino house, the master of which had recently been assassinated by guerrillas for cooperating with the Japanese Military Police. The widow in mourning was alone except for a ten-year-old daughter.

"What shall we do from now on?" said the widow, weeping. "We're already Japanese, and the whole town's against us."

I was trying to console her when two Japanese M.P.'s came in. They looked as if they wanted to be entertained by her, but she would not look at them. I left the house in a dark mood, fearing that similar tragedies would take place if Japan was occupied.

On December 29, a strong reinforcement landed on San Fernando, the 19th Infantry Division from North Korea. Although they lacked one-third of their original force due to the difficulty of transportation, the soldiers were all regular army and looked as if they were of a different race from the exhausted soldiers rescued from torpedoed ships in the Basi Strait while on their way to this country. Robust and lively, the new arrivals marched off toward Baguio.

On New Year's Eve we cooked pork and chicken, and invited Mr. and Mrs. Floirendo, who owned our billet, their brother-in-law, and his servant, an ex-boxer. The brother-in-law was a handsome man with piercing eyes. Judging by his sure manner of speaking and his strong physique, I thought he had been in the army. He told me that he had once been in the Philippine Constabulary. I suspected that he was an important leader of the guerrillas, but guerrilla or not, we had a right to celebrate the New Year. We talked and discovered that we were born on the same day, September 14, 1912. Delighted with this coincidence, we shook hands and drank far into the night. I did not see him the next morning, but I was sure he would become a man of importance if he survived the war .