Table of Contents

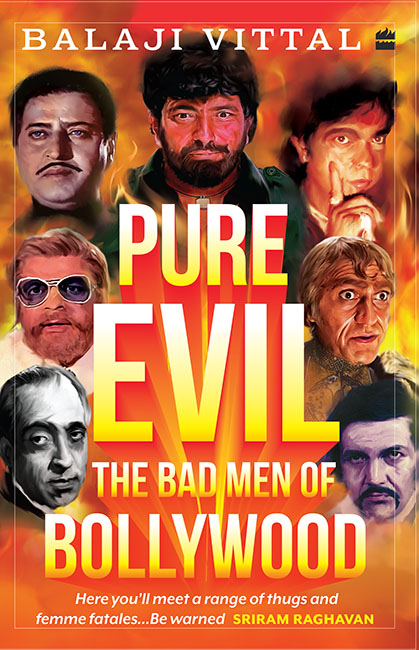

I dedicate this book to the doctors, paramedics, nurses and others in the medical fraternity, the law and order personnel, and the caregivers in India, who risk their own lives every day in the valiant war against the invisible villain. I salute you all.

Contents

I

MERA BHARAT MAHAAN

United against the Outsiders

II

MERE HUMDUM MERE DOST

The Enemies Within

III

BAAGHI

The Outlaws

IV

PAGLA KAHIN KA

The Mentally Ill

V

DON KO PAKADNA MUSHKIL HAI

The Gangsters and the Mafia

VI

TUM LOG MUJHE DHOOND RAHE HO

The Anti-heroes

VII

JAANE BHI DO YAARO

Crime and Punishment

T he first villains in my movie journey were the strict cinema-hall managers in Poona, who kept a hawks eye on kids trying to sneak into Adults Only films. Imagine spending two hours in the advance-booking line, another three hours anticipating the movie and then not being allowed to enter Rahul Cinema to watch Enter the Dragon (1973). A friend even nicknamed his strict father Han after the villain in the film!

One Saturday afternoon, another classmate called me up, saying he had got an extra ticket for the 3 p.m. matinee show of a film playing at Sonmarg. Since my Dad was in the room and within earshot, I told my friend, Yes, I will come and collect the Maths tutorial notes right away. As it was already 2.30 p.m., I cycled furiously towards the cinema hall. I glanced back instinctively and, to my horror, glimpsed my Dad following me on his scooter at a discreet distance. He had obviously smelt a rat. I cycled right past the cinema hall and led Dad on a wild goose chase until I finally lost him. I returned home brandishing a notebook which Id hidden under my shirt before leaving home. I survived the day, though my friend didnt forgive me for making him waste a ticket, and worse, miss the beginning. Quite aptly, the film in question that incident-filled afternoon was titled Paap aur Punya (1974).

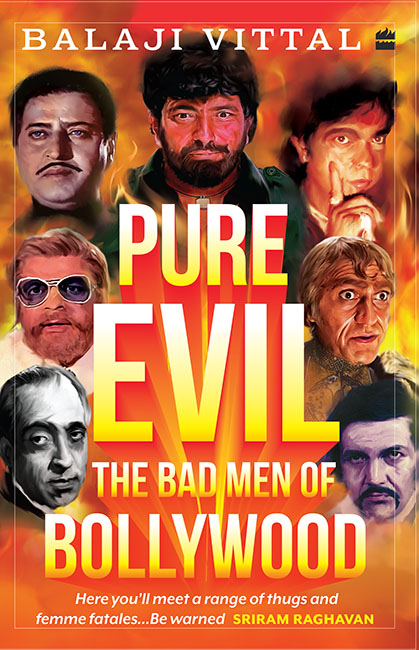

It was in 2019 that Balaji Vittal met me as part of his research for this book. After three excellent works dealing with music in Hindi films, a book about Hindi film villains was a wicked and delicious departure, I thought. And soon we were flashbacking into our childhoods, discussing our favourite baddies and revisiting many forgotten gems and guilty pleasures. Yakub in Paying Guest (1957), Jeevan in Kohinoor (1960), Prem Chopra in Do Anjaane (1976), Bindu in Dastaan (1972) (my favourite), Lalita Pawar as a Chinese spy in Ankhen (1968) and Om Prakash as Seth Dharamdas, who, along with his coterie in Apna Desh (1972), murder an upright schoolmaster What fascinated us most about the last film was the murder weapon: walking sticks. I also remember a newspaper ad for Dharma (1973) starring Pran which said where theres Pran theres life. Suddenly we realized that two whole hours had passed in discussing these bad men. Boy, these villains were memory magnets, we both agreed.

The bad men taught me a lot. I didnt know what catharsis meant but remember experiencing it when Shakaals (Ajit) foot in Yaadon ki Baaraat (1973) gets trapped in the changing lines of the railway track and Shankar (Dharmendra) watches as Shakaal gets mowed down by a speeding train. In Deewar (1975), when Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan) barges into Samants (Madan Puri) bedroom, tears him away from the arms of a woman and throws him down five floors for that moment, I was Vijay.

A few years ago, while researching for a film on Raman Raghav, my meeting with the serial killers psychiatrist made me chuck what I had considered my killer script and make an entirely different film. Dont treat him like a criminal. Remember he was a sick man, he had said to me. Its something I will never forget.

Of course, nobody is a villain in their own story. Take a look at a few of mine: Saif Ali Khans character Karan in Ek Hasina Thi (2004), a charming but lethal character; Neil Nitin Mukesh in Johnny Gaddaar (2007) was a reluctant villain, both tormented and emboldened by his crimeswe consciously decided not to give him a dying close-up in the end. In Badlapur (2015), the hero becomes the villain and vice versa. (In fact, Massimo Carlottos novel, Deaths Dark Abyss, on which Badlapur was based, fascinated me because it went against the grain of every revenge story I had loved.) And Simi in AndhaDhun (2018)? I still wonder if she was a villain or a victim.

In Apna Desh, the villain Dharamdass catchphrase was Narayan Narayan. He invokes this chant as he goes about his heinous deeds. Those were innocent times. Villains in films today have tough competition from real life.

Why do villains fascinate us? Because they neednt follow any rules. And wouldnt we all like that? Whereas the hero always needs to play by the book.

Balajis book is a colourful canvas against which we get to see through the workings of these accursed minds. It talks about the changing social milieu down the decades and how it gave birth to different villains in Indian cinema, ones who made many a moviegoer excited to watch the films on the big screen. It explores how the image of the villains and the nature of their villainy have changed with time. It blends research and our love for the moviesespecially its bad men and womento bring to readers, the film buff, the student, the researcher, and anyone remotely interested in Bollywood, the stories behind and a deep understanding of what makes our villains so alluring. It does so, however, in a language that is easily relatable.

Here youll meet a range of thugs and femme fatalessegregated and classified into various sections based on their brand of villainy; their sources and inspirations; and the great actors behind these characters. For example, the chapter Dhoom Macha Le is all about the technology-savvy, handsome trickster-thieves in the new millennium in films like the Dhoom series, Players, etc., in which the hero and the thief match each others intelligence and smartness.

Like Balajis other books, this one too is meticulously researched and peppered with anecdotes and insights. For example, in his conversation with actor Boman Irani, Balaji discovered how Irani, in preparation for his role of Lucky Singh in Lage Raho Munna Bhai, visited a motor dealers shop owned by a sardarji in Mumbais Lamington Road, and simply sat in his shop and observed him closely. And sometimes, he would also mind the shop when the sardarji would be on a loo break! Also, did you know that the first rape scene in Indian cinema was way back in 1929 in a V. Shantaram film? And that the censors had objected to the scene?

There are some sharp observations around the sartorial details and mannerisms of the villains that breathed life into those characters when we watched them on screen. Reading about those in print rekindled my nostalgia. For example, how Amrish Puri zeroed in on his black and shocking pink costume for the role of Mogambo in Mr India. And how the blonde-coloured duke-wig was needed to create that foreigner look. The book also touches upon the anti-heroes that arrived in the early 1970s, and the dark ensembles represented by classics like Jaagte Raho and Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro.

In this book I was glad to see a mention made of the villains foot soldiers like Shetty, Dan Dhanoa, Mac Mohan, too. A few actors whose iconic villain roles are covered in depth are no longer with us. This book can serve as a fitting homage to those actors.