TO COMFORT ALWAYS

AN

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

BY

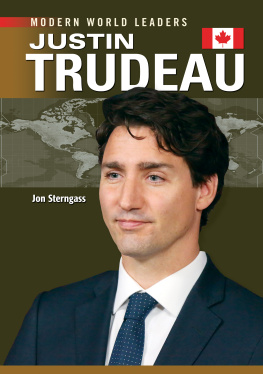

EDWARD LIVINGSTON TRUDEAU, M.D.

Published for the

National Tuberculosis Association

1915

COPYRIGHT 2014 BIG BYTE BOOKS

Get more great reading from BIG BYTE BOOKS

PUBLISHERS NOTES

It is hard for most of us to imagine the great difficulty of living with tuberculosis in the 19 th century, when it was a certain death sentence. Add on top of that the unspeakable sorrow of losing three of your four children and you being to wonder how one would survive with any sort of intact sensibilities.

Yet Edward Trudeau still found the resources in his autobiography to share the humorous side of life. He credits this largely to the influence of his wife and partner, the former Lottie Beare. As he relates below, he nearly gave up the practice of medicine out of a sense of his impending death. But once he again engaged in it, his lifes work became the treating of others with the same disease. With the help of wealthy patrons, he built the sanitarium at Saranac Lake with which he became famously associated. It became the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis with a gift from Elizabeth Milbank Anderson and it was the first laboratory in the United States for the study of tuberculosis. Renamed the Trudeau Institute , the laboratory continues to study infectious diseases.

Trudeau is rightly seen as a public health pioneer of the pre-antibiotic era, recognizing the role of crowding in disease transmission, the utility of isolation of those infected, the practice of disease reporting, and promoting the value of fresh air, exercise, and healthy diet.

Though Im not certain what month this book came out in 1915, by November, Dr. Trudeau had died. A great-grandson of Dr. Trudeau is cartoonist, Gary Trudeau.

DEDICATED

TO MY DEAR WIFE

EVER AT MY SIDE EVER CHEERFUL AND HOPEFUL AND HELPFUL THROUGH THESE LONG YEARS DURING WHICH

PLEASURE AND PAIN

HAVE FOLLOWED EACH OTHER

LIKE SUNSHINE AND RAIN.

FOREWORD

MR. GILBERT K. CHESTERTON, in his review of Mr. Graham Balfours Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, says:

When Robert Louis Stevenson was a little boy, Mr. Graham Balfour tells us, he once made the following remark to his mother: Mother, Ive drawed a man. Shall I draw his soul now?... The only biography that is really possible is autobiography. To recount the actions of another man is not biography, it is zoology, the noting down of the habits of a new and outlandish animal. It may fill ten volumes with anecdotes, without once touching upon his life. It has drawed a man, but it has not drawed his soul.

CHAPTER I.

I HAVE never been very partial to autobiographies, and if there is one thing I thought I would never do, it is to attempt to write about my own life! Nevertheless here I am, falling into what in so many cases has seemed to me in others the great mistake of a mans trying to describe his own experiences and speak of his own work, instead of allowing these to tell their own story, or letting others tell it after he is dead.

Autobiographies must of necessity run perilously near the fatal precipice of egoism, and too many of those I have read have reminded me of the plain old ladies who so often tell us what belles they were in their youth, and what conquests they achieved.

Then why write? First, perhaps, because many autobiographies are certainly of intense interest, instructive and inspiring to others, and because the experiences they describe are in a great measure known to the writer alone, and must perish with him; and because many of my good friends, whom I trust, tell me that the main facts of my life are such as to be of interest to others, and to prove inspiring and stimulating to younger men. In addition, I imagine another reason is that I am human, and that as a man nears the end of the earthly journey, and the evening comes and the shadows lengthen, and the work is done; when there is no longer any future to look forward to in this world and much of the joy of life has disappeared from the present, he naturally turns his face not unwillingly to the past, and is not at all averse to living over again for others some of the days of sunshine and shadow, of pleasure and pain, and of strenuous activity through which he has passed.

I was born in New York City on October 5, 184.8. I had a markedly medical ancestry. My father, Dr. James Trudeau, was a member of a well-known New Orleans family, and my mothers father, Dr. Francois Eloi Berger, was a French physician whose ancestors were physicians for many generations, as far back as they could be traced. My mother, Cephise Berger, was Dr. Bergers only daughter. I had a brother and a sister, both older than myself. My father and mother separated shortly after my birth. He returned to New Orleans with my sister, and when three years old I went abroad with my mother, my brother and grandparents, when Dr. Berger retired from his extensive New York practice, where for many years he held a very prominent place in the early medical history of New York City. While we were abroad my mother obtained a divorce, and married a French officer, a Captain F. E. Chuffart. She and her husband lived in Fontainebleau together until her death in 1900.

I can remember little about my father. I know that during the great Civil War he was an officer in the Southern Army, and for a time had charge Island No. 10; and that he was wounded and brought back to New Orleans, where he partly recovered and practised his profession for a few years before his death. Before the War he married a Miss Marie Bringier, who belonged to a well-known New Orleans family, and who survived him, dying in Baltimore in 1909.

After her death, Miss Felicie Bringier, her sister, sent me a large oil painting of my father in Indian hunting costume, which she said was painted in the early Fortier by John J. Audubon. The distinguished naturalist was a great friend of my fathers, who accompanied him on many of his scientific expeditions, and went with him on the Fremont expedition to the Rocky Mountains in 1841. Miss Bringier states in her letters to me that my father often helped Audubon with the anatomy of his ornithology work, and drew illustrations of birds and eggs for him.

My father not only drew and painted well, but he had a marked talent for modelling in day and making bas-reliefs, and I have in my possession some of his work cast in bronze. I remember my grandfather, Dr. Berger, often saying that my fathers talent for caricature had done him an immeasurable amount of harm professionally in New York, for he made a set of statuette caricatures of the medical faculty, which were so well done and such telling caricatures that many of the gentlemen never forgave him.

The love of wild nature and of hunting was a real passion with my fathera passion which ruined his professional career in New Orleans, for he was constantly absent on hunting expeditions. As mentioned in Miss Bringiers letters, in 1841 he spent over two years with the Osage Indians, who presented him with the buckskin suit in which he was arrayed when Audubon on his return painted the portrait which is now in my possession. This certainly could not have helped him retain his practice.

It would seem that from my father as well as from my mothers ancestors I must have inherited a strong leaning toward medicine as a profession, for after many vacillations and failures in early life, this inherited bent guided me to the choice of a medical career.

This same love of wild nature and hunting, which was a passion in my father, was reproduced in his son, for when stricken with tuberculosis in 1872 it drove me, in spite of all the urgent protests of my friends and physicians, to bury myself in the Adirondacksthen an unbroken wilderness, and considered a most dangerous climate for a chest invalidin order to lead an open-air life in the great forest, alone with Nature and those who were dear to me.

Next page