Contents

Guide

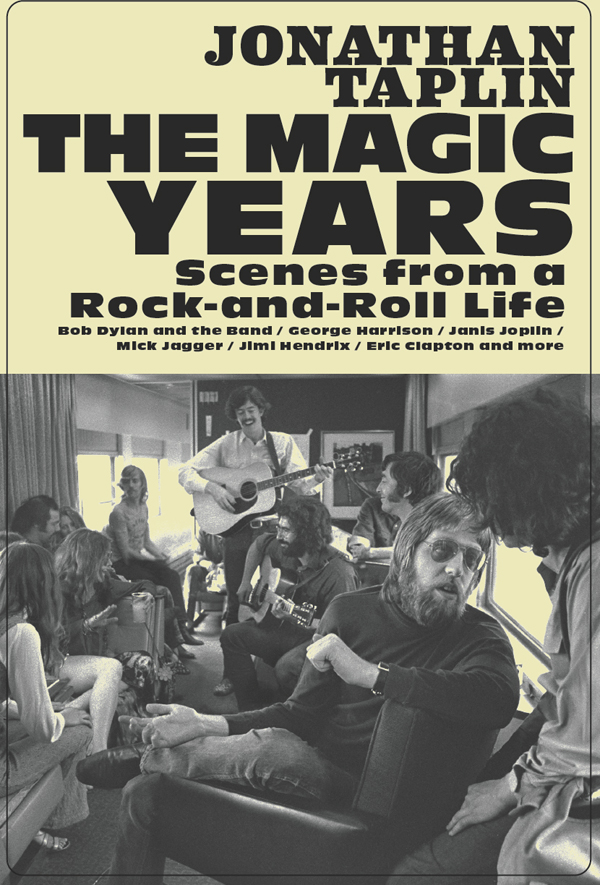

Copyright 2021 by Jonathan Taplin

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Taplin, Jonathan T., author.

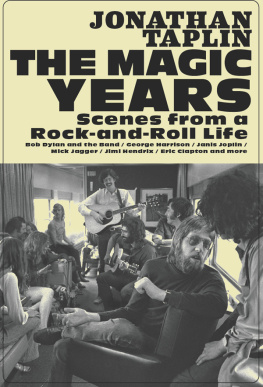

Title: The magic years : scenes from a rock-and-roll life / Jonathan Taplin.

Description: Berkeley : Heyday, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020015947 (print) | LCCN 2020015948 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597145251 (cloth) | ISBN 9781597145268 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Taplin, Jonathan T. | Impresarios--United

States--Biography. | Concert tours--United States--History--20th

century. | Motion picture producers and directors--United

States--Biography.

Classification: LCC ML429.T26 A3 2021 (print) | LCC ML429.T26 (ebook) | DDC 781.66092 [B]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015947

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015948

Cover Photo: Festival Express, 1970, author center right. John Scheele.

All rights reserved.

Endsheet Photo: Woodstock Festival, 1969. Elliott Landy. All rights reserved.

Cover and Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Maggie

and to Daniela, Nicholas, and Blythe

Contents

In its refusal to accept as final the limitations imposed upon freedom and happiness by society, in its refusal to forget what can be, lies the critical function of the artist.

Herbert Marcuse

Show a little faith, theres magic in the night.

Bruce Springsteen

Prologue

Strapped to a Fender Stratocaster electric guitar, Bob Dylan launched into the opening chords of Maggies Farm almost before the band was ready. The Newport Folk Festival of 1965 was going to close with a commotion. I had just turned eighteen, and was an apprentice road manager for Dylans manager. This explosive moment launched me on a lifelong journey, one beyond anything I could have imagined at the time.

I was standing in the stage wing, transfixed, ten feet from the band. Mike Bloomfield, acting like bandleader, brought his Butterfield Blues Band rhythm sectiondrummer Sam Lay and bassist Jerome Arnoldinto some approximation of sync with Dylans rhythm. Al Kooper, in a loud polka-dot shirt, hunched over the Hammond organ and did his best to fill in the spaces, but it wasnt starting well. I ran out toward the mixing booth in front of the stage, where Peter Yarrow had commandeered the board. It was worse out front. In his nervousness, Bloomfield kept raising his guitar volume and was now drowning out everything else. The first tune ended on a sour note and there was only light applause from the audience. I gazed behind me and a look of shock seemed to be the dominant emotion in the sea of blue work shirts and peasant blouses. The man in the tight pants, orange shirt, and dark glasses was not their Bob Dylan. What was going on?

A chorus of boos filled the air before Bob started his radio hit Like a Rolling Stone, but by the end the fans were still booing. Voices from the crowd called for their favorite tunes from the folk era. The band looked nervous, but without a word to the audience Bob plunged into It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry. The band found their groove, but when the tune ended, the booing got worse. Dylan turned to Bloomfield and said, Lets split. To the surprise of the other musicians and the road crew, he unplugged his Fender and walked off the stage.

Instantly the crowd went silent. People started yelling at each other in the aisles. Look what you did! Hes gone, asshole. Peter Yarrow bolted from the mixing console and I followed him backstage. Dylan was sitting on the bottom steps of the stairway leading up to the stage. He was clearly shaken, rubbing his eyes. Peter ran up onto the stage and seized the microphone. Hey, show Bobby that you love him. Lets get him back. The audience roared approval. Dylan sat still on the steps. The audience began to clap in rhythm. Dylan refused to budge. Peter appeared at the top of the stairs, pleading with him to return.

Johnny Cash wandered out of the artists tent holding an acoustic guitar. For a minute he watched the triangular drama of Peter, Bob, and the crowd. He moved over to Bob and handed him the guitar. Play them a song, son. Bob took the guitar and slowly walked up the thirty steps to the stage. When he appeared in a lone spotlight holding the acoustic guitar, the cheers from the audience were deafening. He leaned toward the microphone, raising his harmonica holder. Does anyone have a D harmonica? Out of the crowd, three of Hohners finest sailed through the air onto the stage. Dylan danced out of the way and, grinning, picked up one and placed it in the holder. He started to strum the guitar.

You must leave now, take what you need,

you think will last.

But whatever you wish to keep, you better grab it fast.

Yonder stands your orphan with his gun,

Crying like a fire in the sun.

Look out, the saints are comin through

And its all over now, Baby Blue.

When he finished the song, he rushed through Mr. Tambourine Man, then turned and, without a word, walked quickly off the stage. He had said his piece. They did not own him and, like a lover leaving a bad relationship breakup, he would not turn back.

Great cultural movements are not developed in clarity and order. I could feel that I had just witnessed something profoundly important, but I had no idea what its long-term effects would be. And as I chased the intensity and freedom that Dylans Newport set had allowed me to taste, my life also unfolded in a series of random acts of good fortunebeing in the right place at the right time. I experienced some of the great rock-and-roll moments of the sixties from one of the closest vantage points possible, I found myself in the middle of a new movement in film during the seventies, and I stopped in several more unexpected places on the way to the present. I could never have foreseen where I am now. My current business card carries the title Director Emeritus, Annenberg Innovation Lab, University of Southern California, and I dedicate most of my time to writing and speaking about Big Tech monopolies and examining the great contradictions of the tech revolution. Maybe it seems strange to connect our current culture all the way back to a divisive show Bob Dylan played in 1965. But theyre part of a common story about our culture, and in these pages I tell my version of it.

In 2015 and 2016 I wrote a book called Move Fast and Break Things, which considers the monopolization of the Internet and its destructive effects on society, and especially on artists. That story has become more common in the years since, and here I intentionally do not tell it again. In many ways, this book is the complete opposite.