This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHING www.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1986 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2013, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

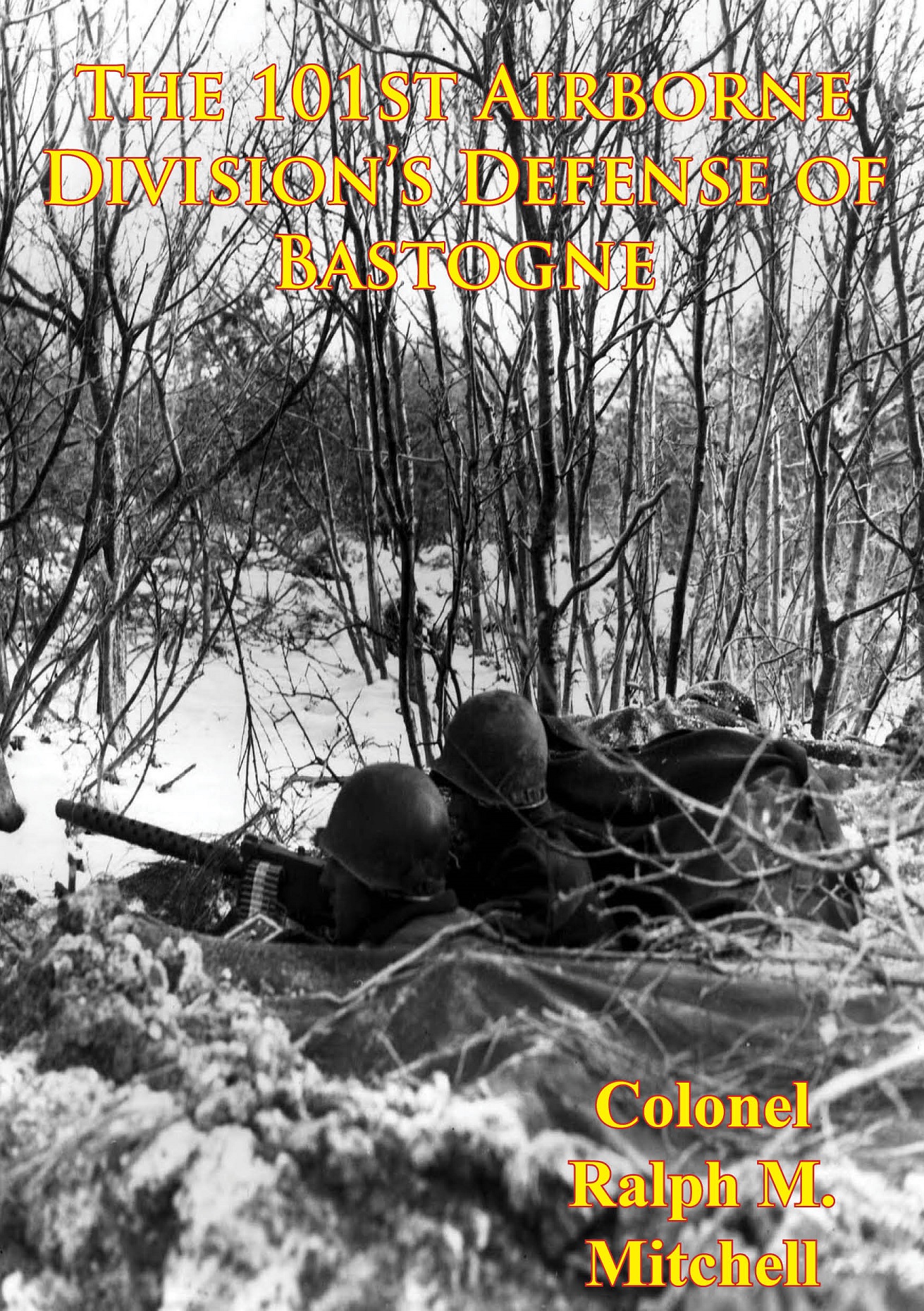

The 101st Airborne Division's Defense of Bastogne

by Colonel Ralph M. Mitchell

September 1986

FOREWORD

The defense of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge in World War II is one of the supreme achievements of American arms. Bastogne is deservedly identified with the finest characteristics of the American soldier, and the name Bastogne symbolizes a heroic battle. Bastogne has long held the attention of students of war, yet the battle offers new insights for soldiers with modern concerns.

Colonel Ralph M. Mitchell's study, The 101st Airborne Division's Defense of Bastogne , reveals how a light infantry division, complemented by key attachments, stopped an armor-heavy German corps. Using original documents and reports, Colonel Mitchell traces the fight at Bastogne with emphasis on the organization, movement and, employment of the 101st Airborne Division. Although a variety of factors influenced the outcome at Bastogne, the flexibility of the 101st to reconfigure for sustained operations and to defeat strong opposition forces even when surrounded shows how properly augmented light infantry can fight and win.

LOUIS D. F. FRASCH

Colonel, Infantry

Director, Combat Studies Institute

CSI publications cover a variety of military history topics. The views expressed herein are those, of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

MAPS

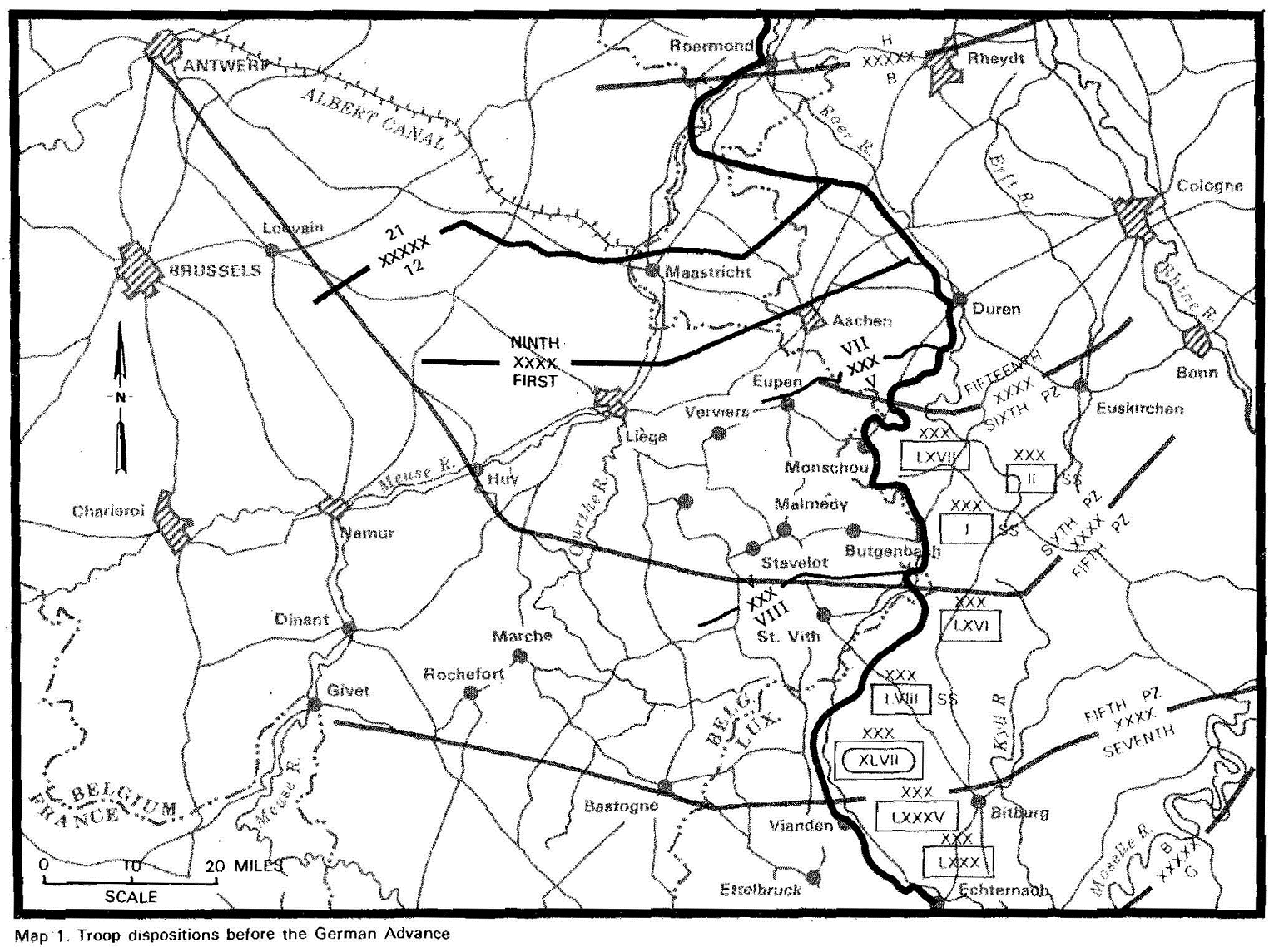

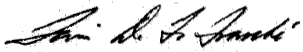

1. Troop dispositions before the German advance

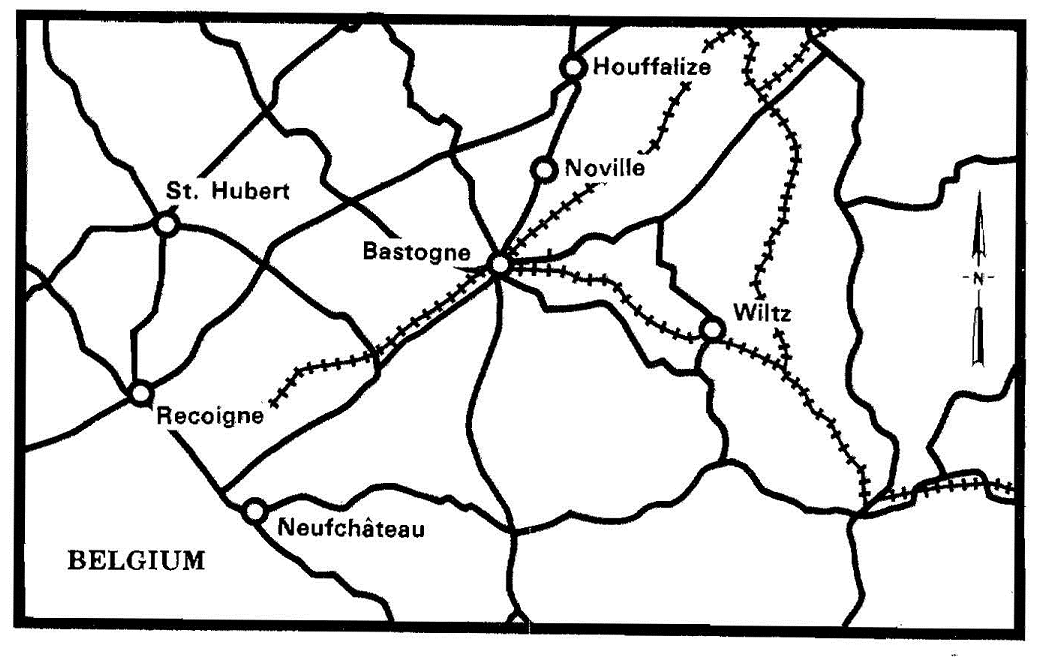

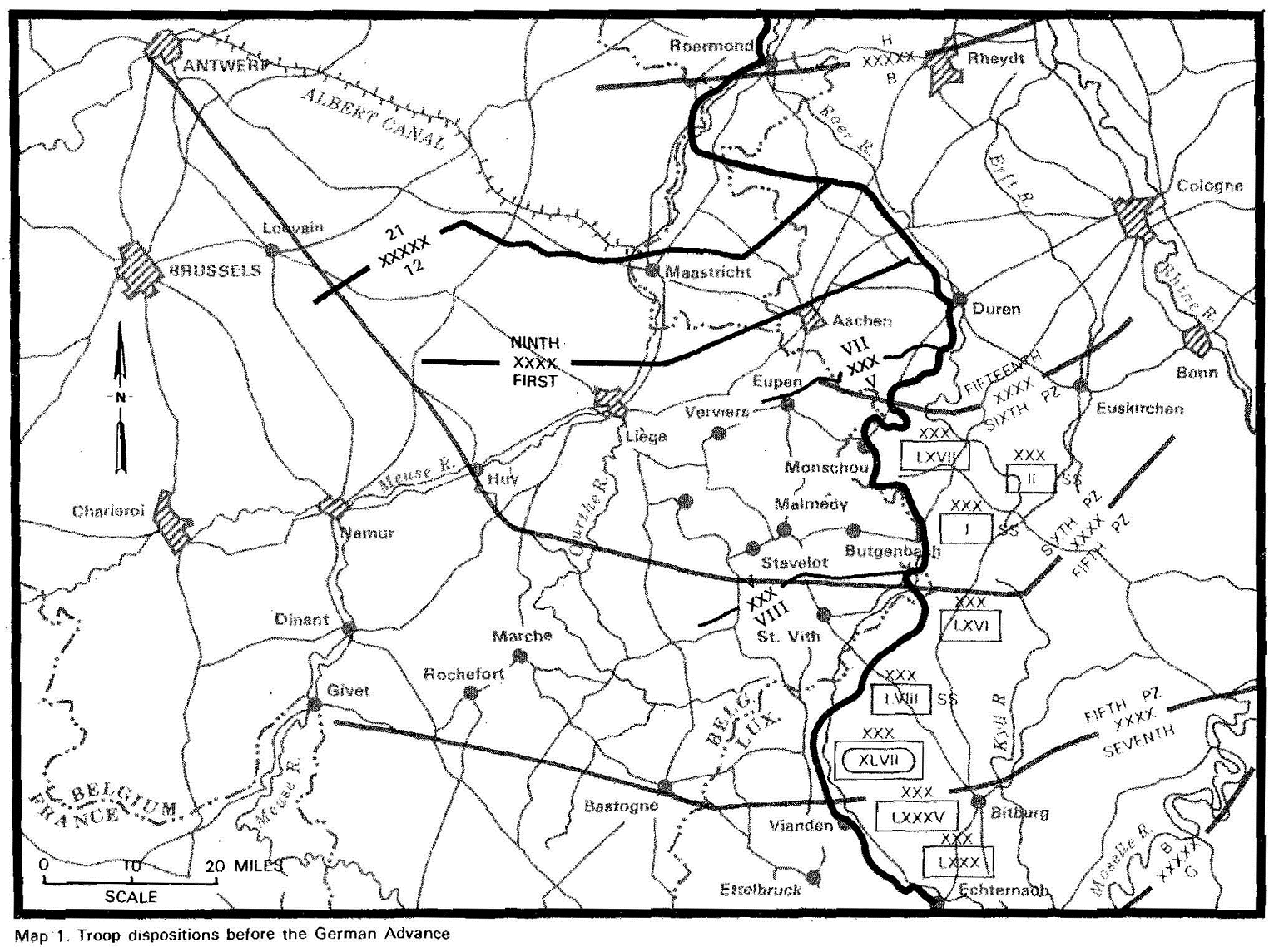

2. The road and rail configuration, Bastogne area

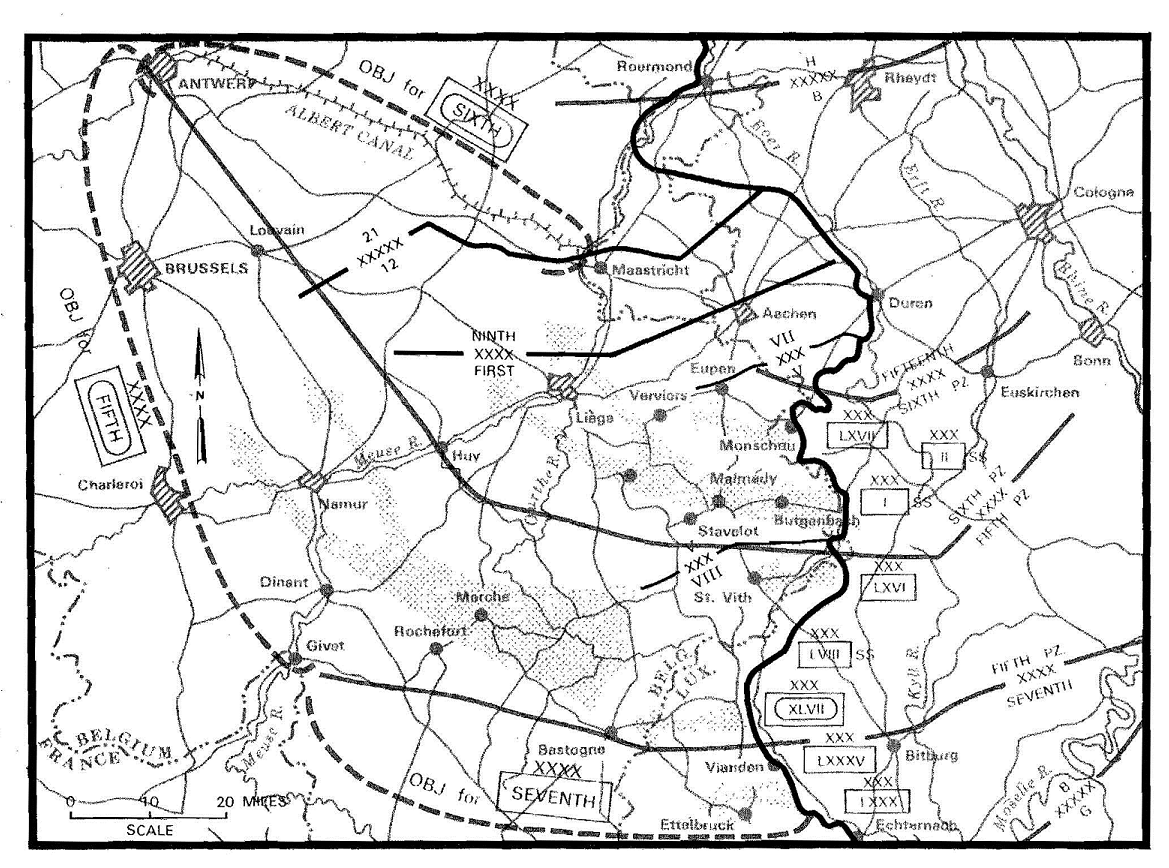

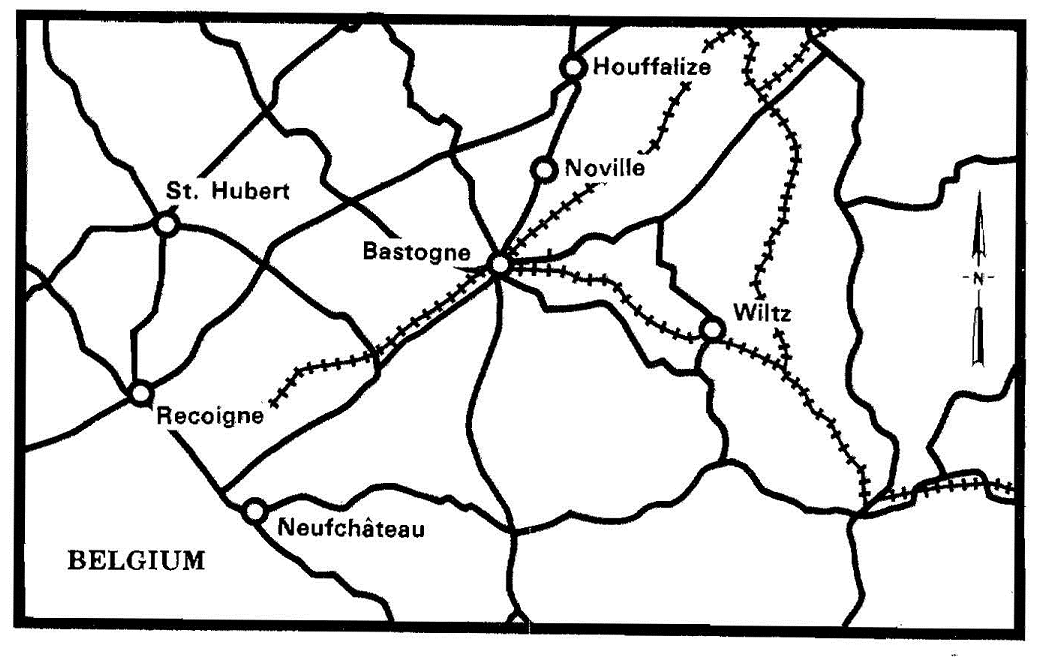

3. The German plan for the Ardennes offensive, December 1944

4. Situation, 19 December 1944

5. Situation, 20 December 1944

6. Situation, 21 December 1944

7. Situation, 22 December 1944

8. Situation, 23 December 1944

9. Situation, 24 December 1944

10. Situation, 25 December 1944

11. Situation, 26 December 1944

I. BASTOGNE: THE CONTEXT OF THE BATTLE

By October 1944, the rapid Allied advance into Germany that followed the breakout from the Normandy beaches had slowed to a crawl. Stiffening German resistance and Allied logistical and communications problems exerted a significant influence on the Allied advance. In the American sector, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley's 12th Army Group occupied an extended front, with the First and Third Armies along the Siegfried Line and the Ninth Army facing the Roer River. There would be little change in these positions in October and November (see map 1).

The First Army had an extensive line of defense near Aachen, Germany. Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton's VIII Corps occupied that army's southern sector. Its 88-mile front extended from Losheim, Germany, north through eastern Belgium and Luxembourg to where the Our River crosses the Franco-German border. The corps' mission was to defend in place in a relatively quiet sector. There, new divisions could receive a safe indoctrination, and battle-weary ones could rest and reconstitute for future operations. Headquarters, VIII Corps, was located in the small Belgian town of Bastogne. The area around Bastogne was characterized by rugged hills, high plateaus, deep-cut valleys, and restricted road nets. Bastogne itself was the hub for seven roads and a railroad. Both sides understood the significance of that fact (see map 2).

Alarmed by the continuing grave situation in the east, Adolph Hitler saw an opportunity for a decisive offensive in the west as the Allied offensive stalled there. Without complete support from his closest advisers, he directed the launching of a winter offensive against the western Allies through the Aisne-Ardennes sector of the front. The purpose was to recapture the important port of Antwerp while encircling and destroying the 21st Army Group. In so doing, Hitler would turn the fate of the war in Germany's favor. Middleton's VIII Corps, however, was directly astride the main avenue of advance of the Fifth Panzer Army.

Few German officers were privy to the plans for this offensive, called Watch on Rhine. Most Germans thought preparations were for defensive measures until a few days before the attack began.

The Germans, however, had identified Bastogne as a possible point of major difficulty and had considered the control of the vital crossroads through that town to be absolutely necessary to maintain their rear area lines of communication. Hitler had expressly ordered Bastogne's capture, and that mission had been passed through Army Group ( Heeresgruppe ) and Fifth Army to XLVII Panzer Corps, which would be attacking through the Bastogne sector. Specifically, the corps was to cross the Our River on a wide front, bypass the Clerf sector, take Bastogne, and move to and cross the Meuse River south of Namur

In light of such specific guidance prior to the operation, it is curious that the Fifth Panzer Army staff did not interpret those instructions the same way. Chief of Staff, Brig. Gen. Carl Wagener, stated, "Bastogne would not necessarily have to be taken but merely encircled. This would avoid any loss of time east of the Maas [Meuse]." The Germans expected that the advance to the Meuse would not be delayed by any attack on Bastogne because both would be accomplished simultaneously. Lttwitz had good reason to be pessimistic.

In the midst of general confusion about the forthcoming operation, pessimism seemed the order of the day, and vital planning went awry. Lttwitz himself doubted whether the offensive would succeed. The Germans had to achieve surprise, and the Allied air forces somehow had to be neutralized. Hitler would have to deliver both a sufficient quantity of fuel and the 3,000 German aircraft he had promised on 11 December 1944. Perhaps the attacking German columns could reach the Meuse, but without divisions to cover their extended flanks and without adequate bridging equipment, there was little hope that they could push farther.

Next page