The trunk on the verandah at Spring Forest, 2016, courtesy Roger Butler

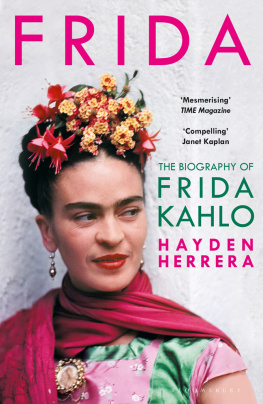

At Spring Forest, the property where Olive Cotton lived for over fifty years, there is a large travellers trunk that originally carried her belongings from Sydney to her new home in the country. At one point, it was filled with her photographs, the negatives and prints from the years spent working at the Max Dupain Studio. These days, the trunk sits on the dilapidated back verandah of the old house, which was Olive and her husband Ross McInerneys first home. It is part of an odd array of abandoned items: nearby is an old fridge, a kerosene lamp, some broken-down machinery, glass bottles and other bits and pieces. Still structurally sound, the trunk is battered on the outside some of its waterproof covering is peeling off but not to the point that any of its contents are endangered. Inside, in no particular order, are notebooks from Olives student days, programs for music recitals and concerts she attended in Sydney in the 1930s, sheet music for piano, and an assortment of books: novels, poetry and plays, some of which were gifts or prizes. One has a book plate in it saying Olive Dupain; another has a handwritten inscription, Love from Daddy. None of these things made it into the new house at Spring Forest, which she and Ross moved into in 1973, and so they were not physically present in her later life. The trunk, in its rundown location, looks unimportant and could easily be overlooked. And yet it is unexpectedly helpful, because it points to the way Olive viewed not only her past, but also her legacy as a photographer.

Olive Cotton didnt fuss about the future. She wasnt one of those photographers who self-consciously assemble and arrange their photographic material, business and personal papers and memorabilia with posterity in mind. She was not at all anxious about controlling her own life narrative and the readings of her photographs. Certainly, she kept things that were important to her the contents of the trunk are proof of that and she ensured that her most valued photographs went into public collections in art museums and libraries around the country. This was a process that started in earnest in the mid-1980s, when her work from four and five decades earlier began to reappear in exhibitions and publications. However, her personal archive, housed in the trunk and numerous cardboard boxes stored inside her home, is informal at best, reflecting an attitude to the past that was benign, verging on the fatalistic. So far as we know, she didnt embark on any dramatic editing or purging, even though there was ample time to annotate or destroy material if she had wanted to the most intimate being a long letter from photographer Max Dupain, whom she married in 1939 and left two years later, and correspondence with farmer Ross McInerney, her husband of nearly sixty years. Olive chose not to intervene and instead left her past open to the future any kind of future free of her dictates and demands.

This position wasnt simply the result of her view on the value of her work and its legacy; it also related to her understanding of time as being beyond human consciousness and experience. As the daughter of a geologist, she was at ease with notions of geological time and its impersonality, and with what others might see as the wearing physical effects of the natural elements. The state of Olives informal archive at Spring Forest suggests that she could accept the deterioration and eventual obliteration of belongings she was once attached to and associated with.

There are pockets of intense fascination in the archive, but it is limited as a potential source of information and illumination, frustrating the biographical process. So few of the items either speak of, or to, Olives inner life. The letters from Max and Ross are revealing, although they say more about each of them than they do about her; she flickers in and out of their writing as the one being addressed but never assumes a firm presence. There are no diaries, only a small number of personal papers and some letters, mostly those she sent to Ross during the war and extended periods in the late 1940s and early 1950s when they were apart. As a biographical subject then, Olive has surprisingly little weight. This is compounded by the kind of person she was her character, her personality, her disposition. A long-term friend, Ernest Hyde, described her as a background figure, which accords with my own view, gained from a professional relationship that began in 1985, when I was Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia, and which later became a friendship. Reminiscences and anecdotal evidence from other people have reinforced this assessment: her reserve, reticence and modesty were commented on frequently, as was her goodness and kindness. Ross told me, proudly, that in their six decades together, he never heard her speak ill of anyone, not once.

During her long career, which spanned two intense phases, from 1934 to 1946, and from 1964 until the early 1990s, Olive never sought the limelight and was not interested in consolidating or extending her influence and reputation. When she spoke about photography publicly, it was only ever her own; she did not comment on the work of others or address the state of photography more generally. On the few occasions she entered into commentary on her work in oral histories (two of which are in the National Library of Australias collection), and in publications it was invariably due to the initiative of others. While she was delighted by the attention she eventually received, and respectful of it, she was, I suspect, slightly bemused by the fuss.

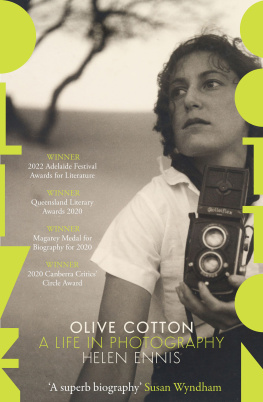

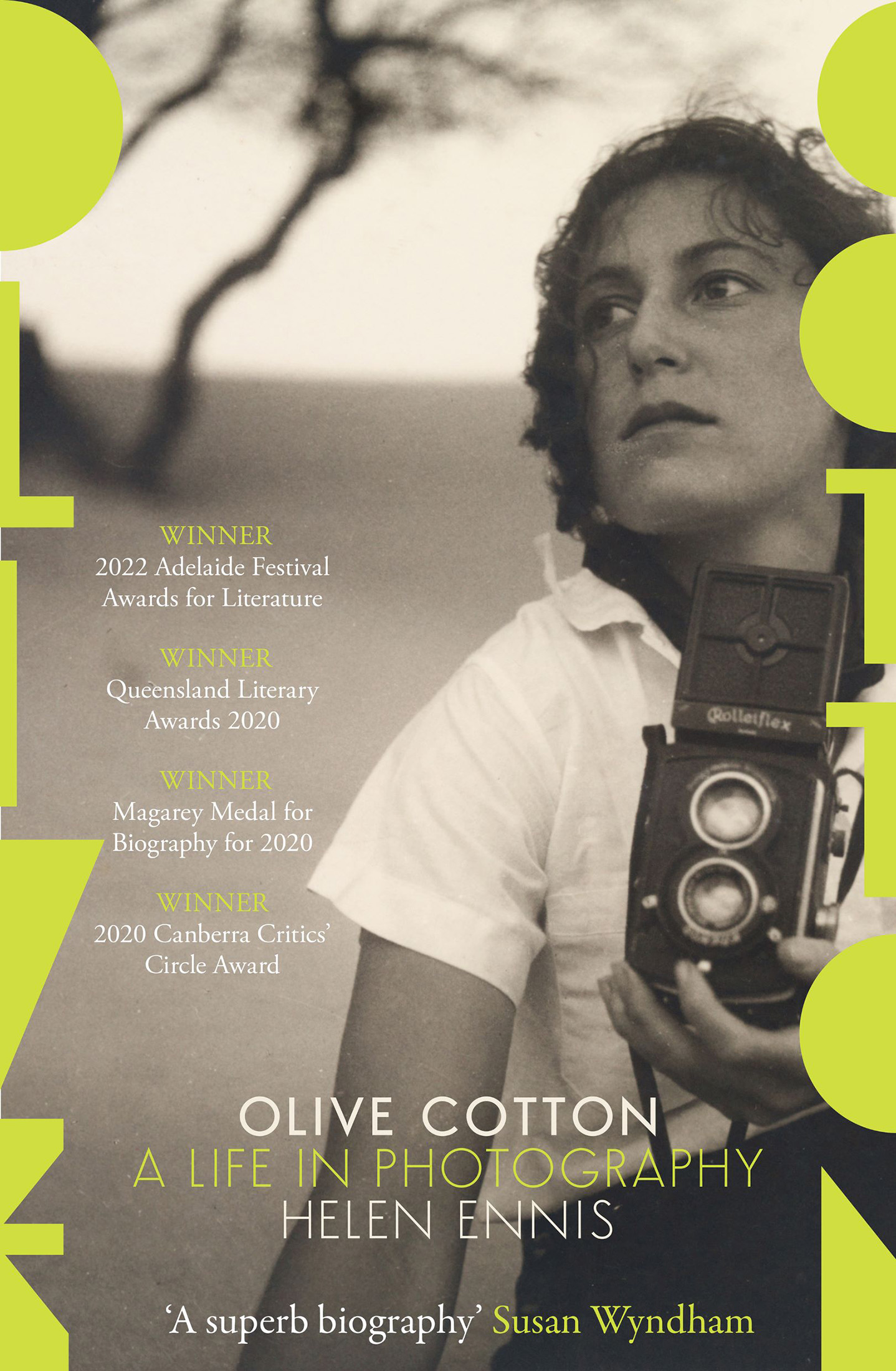

There may not be a large volume of personal documentation, but there are, of course, her photographs the very reason for this biography. Olive Cotton is recognised as one of Australias most important photographers of the modern period. She created a highly original body of work landscapes, flower studies, portraits and still lifes that related to contemporary developments, nationally and internationally, in modernism and modernist photography. Her experimentation with light and its effects, with composition and vantage point, extended the vocabulary of modernism in Australian art to encompass gentler, less heroic modes of expression. Today, her photographs still stand out for their beauty and serenity, and often for their sensuousness as well. In their own quiet way, they have enlarged our sense of the capacity of art photography to move its viewers.

This biography deals with the specifics of Olives life and photographic work, but her story, like everyones, belongs to its own particular historical moment. As a woman whose life spanned nine decades of the 20th century, she was subject to the larger forces and events that defined her times. Born in 1911, three years before the outbreak of the Great War, Olive entered her thirties during the tumult of the Second World War. She studied at university, worked in the photography industry, and for a short time was a high school teacher. She grappled with marriage, divorce, remarriage and motherhood. She experienced gender discrimination in society and culture. She lived in the city and in the country, drew strength from her close family connections and strong enduring friendships with women, coped with personal loss, and dealt creatively with isolation and ageing. Olive also saw the population of Australia grow and its ethnic composition alter, its economic fortunes fluctuate and its geopolitical alliances change as it emerged as a middle power in the global arena. But it wasnt these big socio-political shifts and associated issues that found their way into her art. Her concerns and preoccupations were far more personal, always oriented inwards, rather than outwards. As her sister-in-law, Haidee McInerney, perceptively noted, Olive had another world inside her head The emphasis was his.