Copyright 2017 by John All and John Balzar.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos copyright John All.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

Book Design by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: All, John, author. | Balzar, John, author.

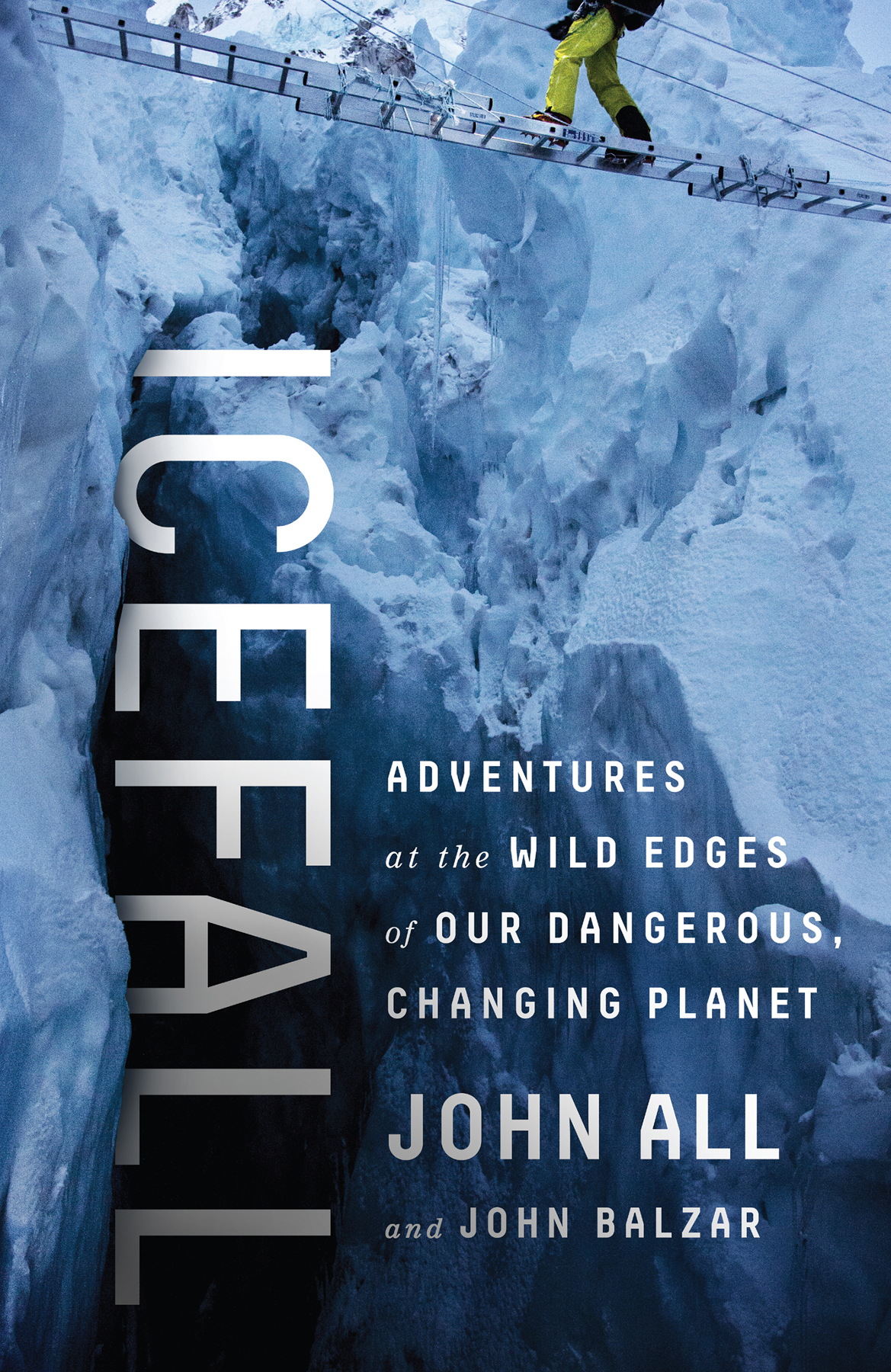

Title: Icefall : adventures at the wild edges of our dangerous, changing planet / John All and John Balzar.

Description: First edition. | New York : PublicAffairs, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029165| ISBN 9781610396936 (hardback) | ISBN 9781610396943 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: All, John. | Global environmental change. | Adventure and adventurersUnited StatesBiography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Adventurers & Explorers. | NATURE / Environmental Conservation & Protection.

Classification: LCC GE149 .A45 2017 | DDC 915.496 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029165

First Edition

ISBN 978-1-610-39694-3

E3-20170204-JV-NF

FOR:

Meggo, the next chapter10/15/16

Oakster, so that you will know me better

Mom and Dad, thank you for the strength and obduracy

Asman, Ill never forget

Balzar, the steady voice

Caroline, I followed your advice.

And my climbing partners: Medler, Rech, Sloan, Nelson, Goldstein, Trainor, Laughton, Leftwich, Benningfield, Harris, and Holmes

Chapter One

O n the morning of May 22, 2014, my plans were in tatters. For starters, I was supposed to be on the Everest massif, many days travel east and south of Mount Himlung, where my tent was now staked on fresh snow at just over 6,000 meters (19,685 feet). But I had been driven off by a climbing disaster, at the time the worst in the history of Everest. So Id journeyed to this peak instead, known to serious mountaineers but not many others. I should have been in the company of the skilled, highly energized team Id brought to the Himalaya on an expedition to collect evidence of the causes of climate change. But after the Everest disaster, their morale had taken a beating, a team member had a worrisome health problem, and for the moment they were scattered elsewhere. I was alone.

Finally, it was seriously late in the South Asian climbing season. Each day brought the dreaded monsoon closerimminent weather that would up the odds for trouble as it approached, then instantly end any hope at all of reaching a mountain summit. The prudent move would have been to retreat for the year. But too much had been invested in this expedition. Sacrifices had been made, big ones. And our work was important, more so all the time. I was not ready to give up.

And besides: I had a spring morning to bask in. I was four miles high in the glory of the Himalaya. A benign sun reflected brightly off the ice. No wind to speak of. The white-tipped fangs of mountainous Nepal soared into the thin sky for as far as I could see, which was hundreds of square miles. I was thinking of coffee.

I wriggled out of my sleeping bag. I pulled on my boots and stepped out of the tent onto the small, flattish snowfield that I had chosen for Camp 2. Cold, bone-dry Himalayan air scalded the lining of my lungs. I grabbed a plastic garbage bag. Mountains are one of the few places on Earth where you must gather fresh water like youre berry picking. Id fill the bag with powdery snow, melt the contents pan by pan on the camp stove, and brew. It was a tedious process, but it meant that the coffee would be all the more wonderful. While I was at it, I figured Id get a head start on the days scientific work and collect the morning snow and ice samples for our study. These too would have to be melted, then filtered and carefully stored so that we could later analyze the accumulated dust and ash and other residue of human industriousness from far-distant cities, farms, and mines. Bit by bit, when analyzed in the laboratory, these samples help us decipher the exact consequences of industrialization on the worlds highest elevations, where climate change is under way in dramatic and, regrettably, life-threatening fashion.

Because I wouldnt be venturing far from the tent, I dressed minimalistwith just wind pants, a T-shirt, a light jacket, and thin glovesno hat, no parka, no headlamp, no satellite phone. Just a quick jaunt out and back. Fill the garbage bag. Light the stove. Then, here on the roof of the world, await that splendid first sip of hot coffee.

Being alone on a Himalayan peak was unwise, and venturing by oneself onto the compressed, fissured, and perpetually moving ice of a glacier was manifestly dangerous, stupid even. I teach mountain safety, and I cannot imagine how many times Id emphasized that fundamental lesson. You had to be skilled, knowledgeable, confident, smart, and lucky. In a place like this, anything less could kill you. This campsite had been methodically scouted. It was plainly the most stable area around. And Id turned the prayer wheels at monasteries down lower as I trekked from Kathmandu.

I stretched, limbered up, and gulped deep breaths to raise my oxygen level. I looked higher up the mountain, and for a moment my thoughts drifted to the climbing route that would await us in a couple of days, after the remnants of my team returned here to Camp 2 from lower elevations. Ice cliffs directly above me meant we would have to pass to one side or the other. I pondered the choices. To my left and not very far above, I saw a flat area of snowpack that would provide a different vantage on the upcoming route. Plus, it was a perfect spot to gather snow samples and fill up the garbage bag.

I set out in that direction. One step another. Another. I was not counting.

I took one step too many.

Vertigo. Blackness. So fast. Impossibly fast. My footing vanished. My face smashed into jagged ice. I disappeared into the guts of the glacier. Sliding. Bouncing.

Theres no accounting for the shape of a glacial crevasse. It could be a simple narrowing V that pinned you in place before you reached the bottom. Or it could be an irregular crack that descended for a thousand feet. Or a small crack might open into a giant cavern. Honestlyhow would you know? Until you fell in.

Smash. Pain.

I plummeted, but not straightaway downward. I crashed into one uneven, abrasive side of the hard ice, and then bounced into the other side and careened back. Crunch. The parallel sides of ice widened instead of narrowing. And wherever the bottom might be, it was farther down still. Way down. Down and down and down more, into blue-blackness deep in the heart of this ancient ice.