I am deeply indebted to Steven M. L. Aronson, my brilliant editor and lifelong friend, who greatly enhanced my narrative by suggesting that we include letters and news clippings that he found in family archives and scrapbooks; to my nephew Sheldon Pennoyer and my niece Jen Pennoyer Emerson who found my mothers scrapbooks as well as ninety-eight letters from Grandfather Morgan to my mother that provided material for my story; to my friend Gary Ferdman for the photograph of the Anne Morgan plaque; to the personnel at Modernage who reproduced, with the greatest attention to detail, the photographs that I provided, and helped locate additional photographs on the web, including the photograph of the landing at Iwo Jima; and especially to David Wilk whose team designed the book and the book jacket, and led me through each step of the publication process with professionalism that meets the highest standards in quality and design.

I could not have written this book without my dear friend Agnes M. Otten, who has assisted me in my law practice over the past twenty-eight years, and over the past three years has typed and retyped successive drafts of the manuscript.

Above all, I am indebted to my children, Christy, Russell, Tracy, and Peter, who urged me to write this memoir so that my progeny would know their roots and the lessons I have learned.

I was born in the third-floor nursery of my grandfather J. P. Morgans house at the corner of Thirty-seventh Street, now part of the Morgan Library and Museum. The date was April 9, 1925. My father, Paul Geddes Pennoyer, was pacing the entrance hall at the foot of the stairs when my grandfathers head butler, the famous Physick, called down from the second-floor landing, Sir, its a girl! As my father reached for his hat to go down to Wall Street, Physick added, Wait, sir, theres another on the way!

In due course we newborn twins, Kay and I, were taken home. Home was always Round Bush, on Duck Pond Road in Glen Cove, Long Island. Except for the two years my parents lived in Paris when my father ran the French office of White & Case and the four years they spent in Washington (in what my father described as a minute house in Georgetown) during the Second World War, my mother lived continuously at Round Bush from 1918 until her death, in 1989.

My parents had married on June 17, 1917, in the Episcopal Church of St. Johns of Lattingtown, in Locust Valley. My grandfather was the senior warden and occupied the first pew on the right (we Pennoyers were relegated to the fourth row). Every Sunday he could be counted on to pass the collection plate at eleven sharp (he was fanatical about punctuality). My brother, Paul, remembered how after the service Grandpa would pour the proceeds into a green felt drawstring bag and deposit it in the Morgan bank the next morning. He had helped found the church in 1912, and was responsible for the intricately carved paneled oak interior hed had made in Scotland, over the course of five years, as an exact replica of the little Thistle Chapel of medieval knights in Edinburgh, and then shipped to Long Island in bits and pieces. After World War II my mother, who did lovely needlework, embroidered a needlepoint image of the church on the curtain that is mounted on the panels to the right of the altar. It took her three years to complete; she said it was a genuine labor of love.

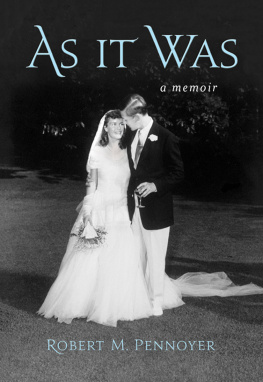

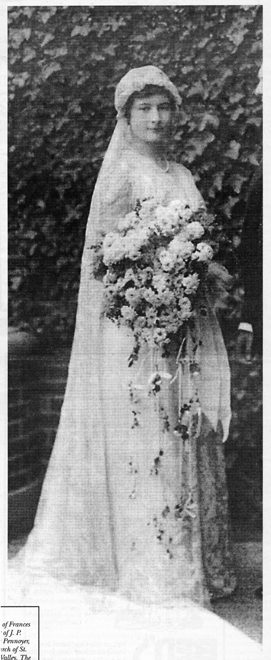

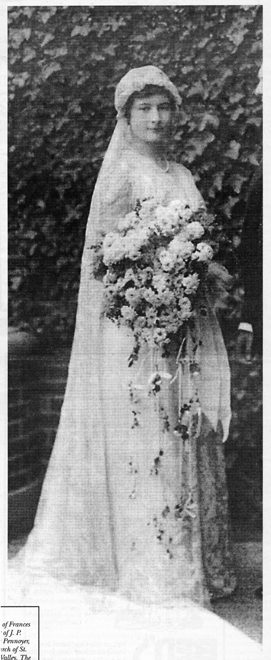

On her wedding day, she had worn a silk-illusion dress embroidered in a floral motif and trimmed with orange blossoms and genuine seed pearls, fashioned by the venerable Worth of Paris. It was probably the only truly splendid dress she ever owned, and half a century later she donated it to the Museum of the City of New York. She told me she would have preferred a very small wedding but that her mother and father felt people would think they disapproved of the match if they did not invite a few hundred guests.

My father had just graduated from Harvard Law School. For several years he had been training in the army reserve at Plattsburgh and, when America entered the war in April 1917, he had wanted to enlist on active duty, but was dissuaded by his prospective father-in-law, who told him in his customary no uncertain terms, You had better graduate and finish that chapter. As a Harvard undergraduate, my father had belonged to the Delphic Club, which Grandpa Morgan had helped to found when he was at Harvard. As a member of the Gas House (as Delphic was known), Dad had become good friends with my mothers older brother, my beloved Uncle Beak (Junius Spencer Morgan), who one weekend in 1915 brought him home to Matinecock, my grandfathers estate on East Island in Glen Cove, where he met my mother who was then only eighteen.

Frances Tracy Morgan at her wedding, June 17, 1917

On their first meeting my father won my mother over by immediately calling her by her nickname Bowser, a dog in a favorite English childrens book of hers. (When my mother first met my wife, Vicky, she asked her to call her Aunt Bowser.) They got engaged at Camp Uncas, Grandpa Morgans place in the Adirondacks, during a large house party. He and my grandmother were in England, and my mother and her older sister, Jane, had been left in the charge of a chaperone, whom they called the dragoness behind her back. There was a big storm and the house party was housebound. The rest is history.

The summer of his wedding my father was commissioned in the army as a lieutenant, and in April 1918, when my sister Virginia, whom we called Dina, was only a month old, he went to France with the American Expeditionary Forces commanded by General Pershing. Because he knew French he was saved from fighting in the trenches, and served as liaison to the French army. Forty years later, as his liner approached the French coast at the end of a transatlantic crossing, he recalled arriving in France in 1918:

I am writing in the bar and I can see France. Looks as good as when we made it on the S. S. Northern Pacific in 1918. [I] remember how good it was to get ashore and to march out to some Napoleonic barracks outside of Cherbourg. And I was able to get into town a few times and dig up a French teacher to give me French lessons. Paid dividends. When the regiment (305th Field Artillery, Henry L. Stimson, C.O.) left for Bordeau I was left behind because of my allegedly exquisite French to find the lost regimental baggage which arrived in spite of me!

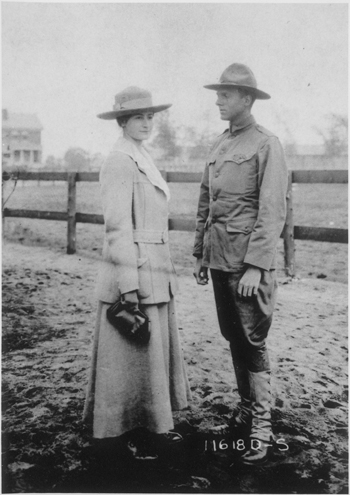

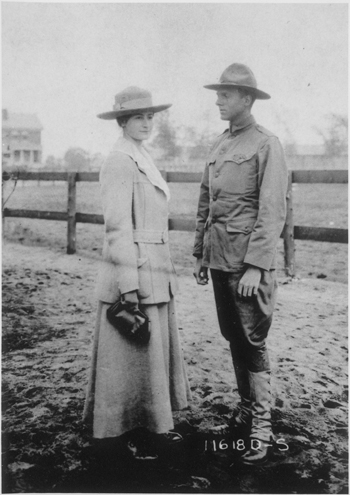

Paul and Frances Pennoyer at the army camp in Plattsburgh, New York, in 1917 before he went to France

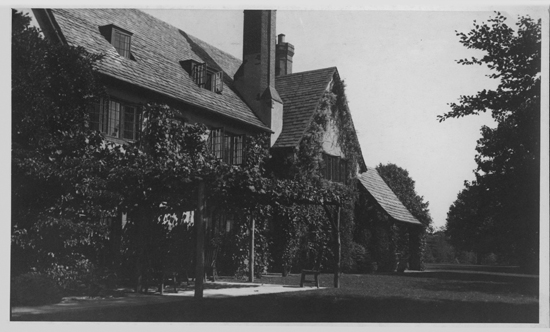

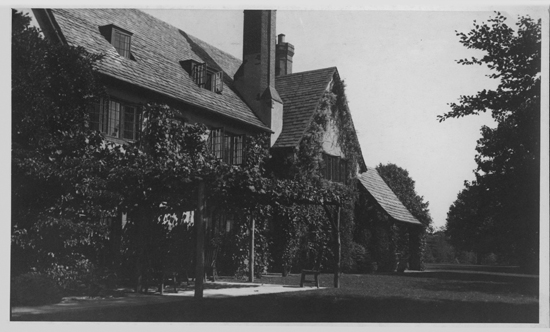

Round Bush, with the terrace on the south side, the grape arbor, and the veranda at the end

After he returned the next May, my brother Paul was born in 1920; my sister Tracy in 1921; Kay and I in 1925; and Jessie, named for Grandmother Morgan, a year later.

Just before my father went off to war, Grandpa Morgan had commissioned the architectural firm of Goodwin, Bullard and Woolsey to build Round Bush, a picturesque English-style country house of brick, stucco, and slate. The house featured at least twenty-three rooms, in addition to a seven-car garage, six-stall stable, pig sty, chicken pen, tennis court, squash court, and fifty-foot swimming pool. It sat on a hill overlooking more than fifty acres of fields, woods, and pasture. There were abundant flower gardens and several acres of vegetable gardens. It was named Round Bush after a hamlet near my grandfathers estate north of London, Wall Hall, where my mother grew up, and had a perfectly round English boxwood bush at the center of the circular drive near the front entrance.