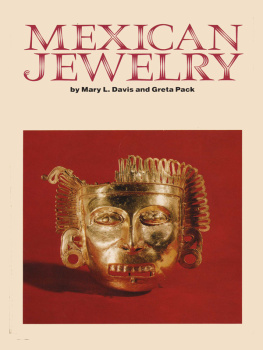

Mexican Jewelry

Mary L. Davis and Greta Pack

with drawings by Mary L. Davis

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 637435

Library ebook ISBN: 978-1-4773-0587-4

Individual ebook ISBN: 978-1-4773-0588-1

DOI: 10.7560/733053

Copyright 1963 Mary L. Davis and Greta Pack

Copyright renewed 1991

All rights reserved

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

FOR ELIZABETH DAVIS FURST

At the end of a seminar conducted in Mexico by the Committee on Cultural Relations with Latin Americaa seminar during which we had gone on trips, listened to lectures, and had contacts with authorities on many phases of life in MexicoHubert Herring said something like this, Now that you have had a concentrated introduction to Mexico, come back next year and enjoy life here. This advice we have proceeded to follow during a number of visits.

Our interest in the beautiful creative crafts of the country grew and grew, specially our interest in the jewelry craft. From admiration for the modern work our enthusiasm came to include the jewelry worn by the country people which we saw as we traveled about. We discovered that there is a large and growing group of collectors mainly interested in regional design and craft work. And as more and more is coming to light concerning the far distant past of the Indians, our amazement at their skill and their expressive design has increased. Containing, as it does, all this inseparable material in one short volume, this book can be no more than an introduction to the subject. We have had to omit all discussion of the larger metal work which is so closely related to the jewelry, and which is being done by the same craftsmen; we have concentrated our comments on the personal ornaments and trinkets with which people instinctively adorn themselves in an attempt to be beautiful and/or attractive.

Mexico is a complicated society of many worlds. The tourist world is one, and a Yankee is always a gringo, say what you may. Each little break in the wall which separates the tourist from the Mexicans is gratefully explored. When one has an interest in common with the Mexicans he meetseven an interest in jewelryone can feel a little better acquainted with a people and a country one cannot help but like.

We would like to record our thanks to Mr. Frederick Davis who, before his death in 1960, helped us as we were starting our study for this book by expressing his enthusiasm for our plans, and by discussing his collection with us and allowing us to photograph many items. And our thanks also to the photographer, Sr. Antonio Garduo, who made those photographs for us, as well as many others, inasmuch as he had access to the museums, and who hunted through his forty years accumulation of beautiful negatives for pictures which might be of use to us.

William Spratling has been especially helpful and generous, as have a number of other jewelry makersSrs. Antonio Castillo, Salvador Tern, Antonio Pineda, Hctor Aguilar, and Enrique Ledesma, and the late Srta. Matilde Poulat. Sr. Ernesto Cervantes told us many things about the Oaxaca jewelry as did also Sr. Carlos Bustamante in Oaxaca. Mr. M. Lampell has taken time to give us an insight into the problems and point of view of the jewelry dealer.

A busy friend, Ethel Comstock, hunted up missing facts and figures for us in Mexico when we were not there. Frances Bristol, in the midst of her research on native costume, kept her eye open for items about jewelry for us. The intrepid driving of Louise Green carried us hither and yon in her car. Elizabeth Furst gave us valuable help and advice, typed for us, and fed us when we were hungry. Muchas gracias.

We must also mention the Baker Library at Dartmouth College, which, during a time when we lived in Vermont, allowed us to take home, armload by armload, dozens of books from their fine Mexican and Art shelves including some books which we had thought to be unavailable.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Designs from

Churches and Other Old Buildings (drawing)

The Mexican Style

THE SPANISH LOVE of rich, dramatic effects and the Indian talent for expressive decoration together have produced that unique and vigorous hybrid, the Mexican style in art. Occasionally a piece of craftwork seems almost pure Spanish or pure Indian, but one will find very few art forms completely unaffected by the four-hundredyear mingling of the two cultures.

In a small southwestern section of the United States the jewelry craft, taught to the Indians by the Mexicans about a hundred years ago, still retains some of the Mexican character. The stamped decorations of the Navajos, the squash blossom, the inverted crescent pendant, the stylized butterflies, all are survivals of Mexican design changed by the Southwest Indians to suit their own taste. But in Mexico Spanish-Indian is the prevailing style, taken for granted by the Mexicans, but so exotic to the visitors from the north that it excites their enthusiasm and admiration.

The temperament and the economic and cultural condition of a people are indicated by their jewelry as well as by their clothing and customs. In the United States the people, more or less classless and comparatively well off, can buy jewelry to fit every pocketbook and every kind of taste. The majority, in this machine age, are content with mass products which follow a constantly changing fashion. The production of individual pieces by hand is small and exclusive. In contrast to this, in Mexico the jewelry is practically all handmade, although some of it is mass produced by many hands with the American tourist in mind.

To many people Mexican jewelry suggests heavy silver decorated with so-called Aztec motifs, set with green or black stones, and ornamented with domes and balls to make it look primitive. This is the style which originated in the 1920s when the Mexicans started making silver jewelry for the tourists. The original pieces were eagerly bought by the tourists, and the designs were copied by hundreds of silversmiths who had learned the processes of jewelry making but could not design for themselves. The good pieces, set with jadeite and obsidian, retain their original beauty, but the imitations, set with dyed stones and made of thin silver, lose the harmony of design which the originals had and, like all art work which has been reproduced in thousands of copies, achieve the monotony with which we are so familiar in mass-produced costume jewelry.

The variety which must be included in the category of Mexican jewelry is surprising if the work of four hundred years is examined. The style has not developed in a steady growth and evolution, but has been influenced by many conditions. Interesting jewelry is being made in all parts of the country, in big modern workshops and in little home shops where the work is done with simple, traditional tools. And the products may be gold jewels set with precious stones or crudely worked silver set with colored glass. Students of folk-craft are not interested in the new sophisticated jewelry, and people who prefer traditional things like only the gold and filigree work. In this study we do not consider the luxury jewelry sold in the cities, jewelry which is really international in style.

AUSTIN

AUSTIN