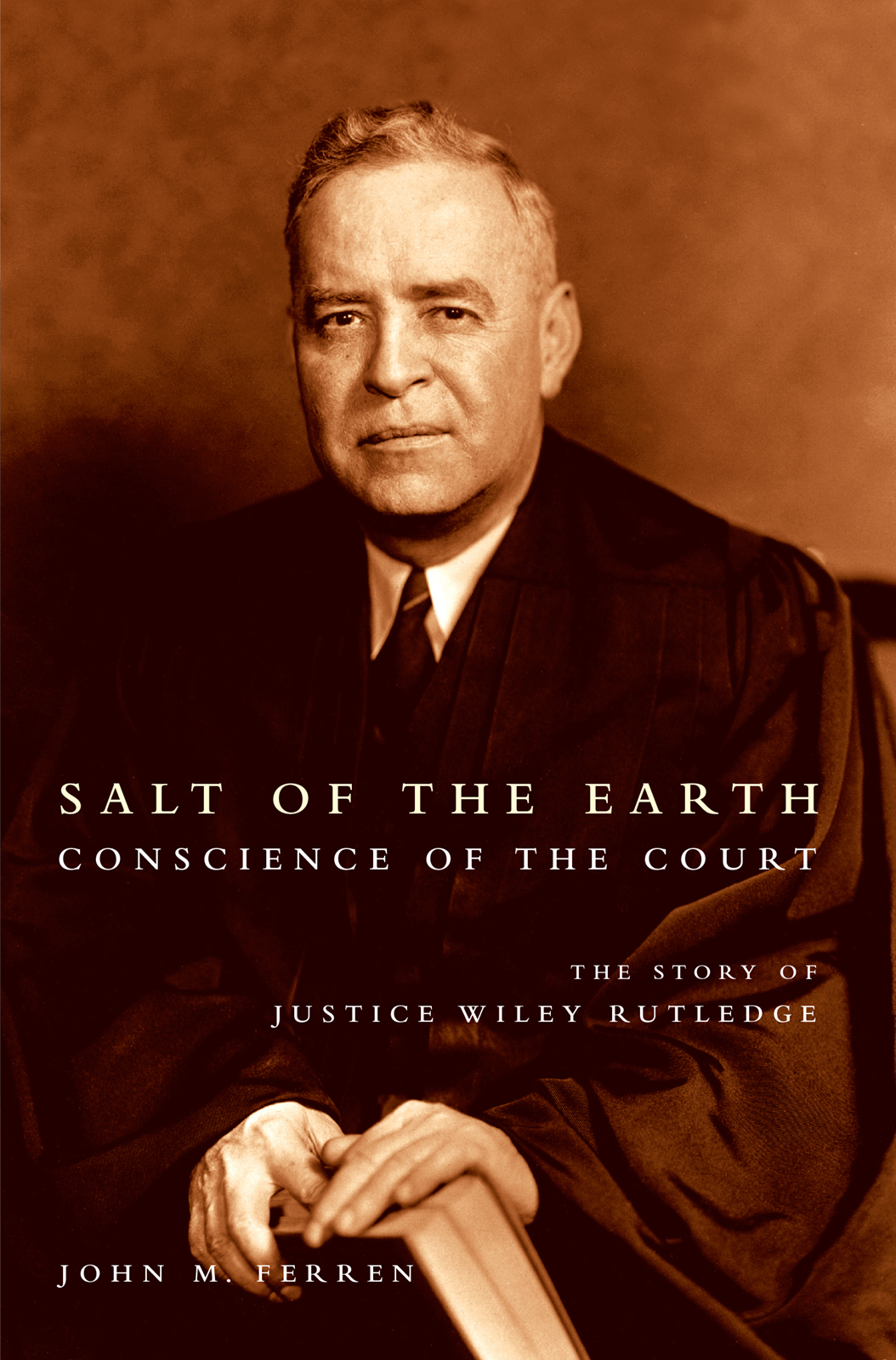

Salt of the Earth, Conscience of the Court

The Story of Justice Wiley Rutledge

John M. Ferren

The University of North Carolina Press

Chapel Hill and London

Publication of this book was supported in part

by a generous grant from the Supreme Court Historical Society.

2004 John M. Ferren

All rights reserved

Designed by Charles Ellertson

Set in Ruzicka with Melior display

by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Portions of the introduction and Chapter 19 have been published as

General Yamashita and Justice Rutledge, 28 J. Sup. Ct. Hist. 54 (2003).

Portions of Chapter 15 appeared as Military Curfew, Race-Based

Internment, and Mr. Justice Rutledge, 28 J. Sup. Ct. Hist. 252 (2003).

The paper in this book meets the guidelines

The paper in this book meets the guidelines

for permanence and durability of the Committee

on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ferren, John M.

Salt of the earth, conscience of the court: the story of Justice Wiley Rutledge /

John M. Ferren.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8078-2866-1 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Rutledge, Wiley, 18941949. 2. JudgesUnited StatesBiography. 3. United States. Supreme CourtBiography. I. Rutledge, Wiley, 18941949. II. Title.

KF 8745. R .87F47 2004

347732634dc22 2003027752

08 07 06 05 04 54321

THIS BOOK WAS DIGITALLY PRINTED.

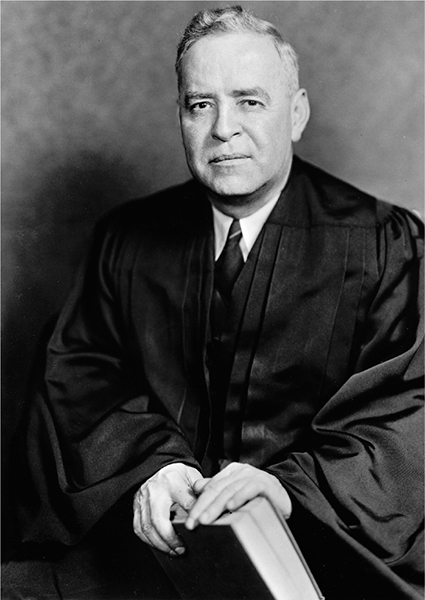

Frontispiece: Justice Wiley Rutledge upon joining the Supreme Court. (Photograph by Harris and Ewing; Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1943.8.2)

For Linda, who makes all the difference

Ye are the salt of the earth.

Matthew 5:13 (King James)

In reflecting over a lifetime in the law, a former clerk

of Justice Douglas remarked not long ago: If I were a

defendant being tried by a single judge, Id rather have

Justice Rutledge than any judge I have known.

Lucile Lomen, March 28, 1996

Wiley Rutledge truly liked people. Regardless of station.

And that led to everything.

Contents

Illustrations

Salt of the Earth, Conscience of the Court

INTRODUCTION

Yamashita

At 2:30 in the morning on February 23, 1946, in a small country village south of Manila in the Philippines, Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita of Japan was told, Its time. Not three weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court had denied his request for reviewwith Justices Wiley Rutledge and Frank Murphy dissentingGeneral Yamashita, the Tiger of Malaya, was hanged.

Yamashita had earned his title by taking Singapore from the British in January 1942 with but 30,000 men to Britains 100,000. Yamashita, clearly, was a brilliant strategist. But no tiger. Although he was a heavily muscled bear of a man, he was a calm soul, a lover of nature. He outspokenly had opposed war with the United States and Great Britain, and thus the Tojo faction rising in Japan had despised him. The Japanese high command had needed Yamashita in Malaya, but straightaway thereafter Hideki Tojo assigned him to an outpost in Manchukuo for the next two and a half years. When Saipan fell in July 1944, and Tojo and his cabinet resigned, the successors in power recalled Yamashita to defend the Philippinesa hopeless proposition, he discovered. Also named the Philippines military governor, Yamashita took control of Japans 14th Area Army on October 9, 1944, when American invasion was imminent.

Less than two weeks later, General MacArthur landed on Leyte Island midway along the Philippine archipelago while the Pacific Fleet was crippling the Japanese navy in Leyte Gulf. General Yamashita devised a plan to defend the Japanese occupation on the large northern island of Luzon in the mountains around Manila. He then had but 100,000 troops, the Americans more than 400,000. On January 9, 1945, MacArthur reached Luzon and advanced toward Manila. Yamashita had not declared Manila an open city, outside the battle zone, because he depended on supplies stashed there. He left a skeleton force in Manila to inhibit the American advance while his main forces withdrew. Although Yamashita had gained effective control over the air force and ordered it out of the capital city, he had not been able to assume authority over the navy, which left a force of 20,000 in Manila after informing Yamashitanow in mountain headquartersthat 4,000 would remain. Contrary to Yamashitas orders, moreover, his subordinates, in discussions with the Japanese naval commander, Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, did not negotiate a timely naval retreat from Manila. Although on paper Iwabuchi was under Yamashita, he complied instead with Vice-Admiral Desuchi Okuchis order to remain in Manila, destroy all naval facilities, and fight MacArthur to the death. As a result, Mac-Arthurarriving on February 3trapped the imperial navy.

In his headquarters 125 miles north of Manila, Yamashita had not been able to learn how rapidly the Americans were advancing, but by mid-February he realized the situation and, for the second time, ordered the Japanese navy out of Manila. It was too late. By March 3, Japans naval and residual army forces there, including Admiral Iwabuchi, were dead. In holding out as long as they could before the Americans wiped them out, however, Iwabuchis navyfilled with liquor and ordered to take enemy liveshad spread out as a drunken mob to rape, torture, shoot, and burn. Young girls and old women were raped and then beheaded; mens bodies were hung in the air and mutilated; babies eyeballs were ripped out and smeared across walls; patients were tied down to their beds and then the hospital burned to the grounduntil MacArthurs forces, fighting Japanese sailors hand to hand, ended the atrocities.

To this day it is unknown whether Yamashita at the time had any idea of the carnage. He had divided his forces into three groups: one under his direct command in the mountains well north of Manila, another under Lieutenant General Shizuo Yokoyama to the east, and the third under Major General Rikichi Tsukada to the west. Yamashitas communications within his own group, as well as with the other two, ranged from limited to impossible. General Yokayamas troops, in the meantime, were harassed by Filipino guerillas making way for MacArthurs advancing forces, and, in a fateful decision, Yokoyama left guerilla controlwithout issuing guidelinesto his field commanders. As a result, one of his colonels, Masatoshi Fujishige, leading his Fuji Force, deemed as enemy guerillas all civilians in Fujis way, including women. [K]ill all of them, Fujishige ordered. By the time the Americans liberated the area east of Manila, the Fuji Force had massacred 25,000 of the estimated 30,000 to 40,000 civilians slain by the retreating Japanese in Manila and southern Luzon. Isolated from both Yokoyamas and Tsukadas forces, General Yamashita retreated with his own troops northward, resisting American attacks until September 3, 1945, when he surrendered all Japans forces remaining on Luzon.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines

The paper in this book meets the guidelines