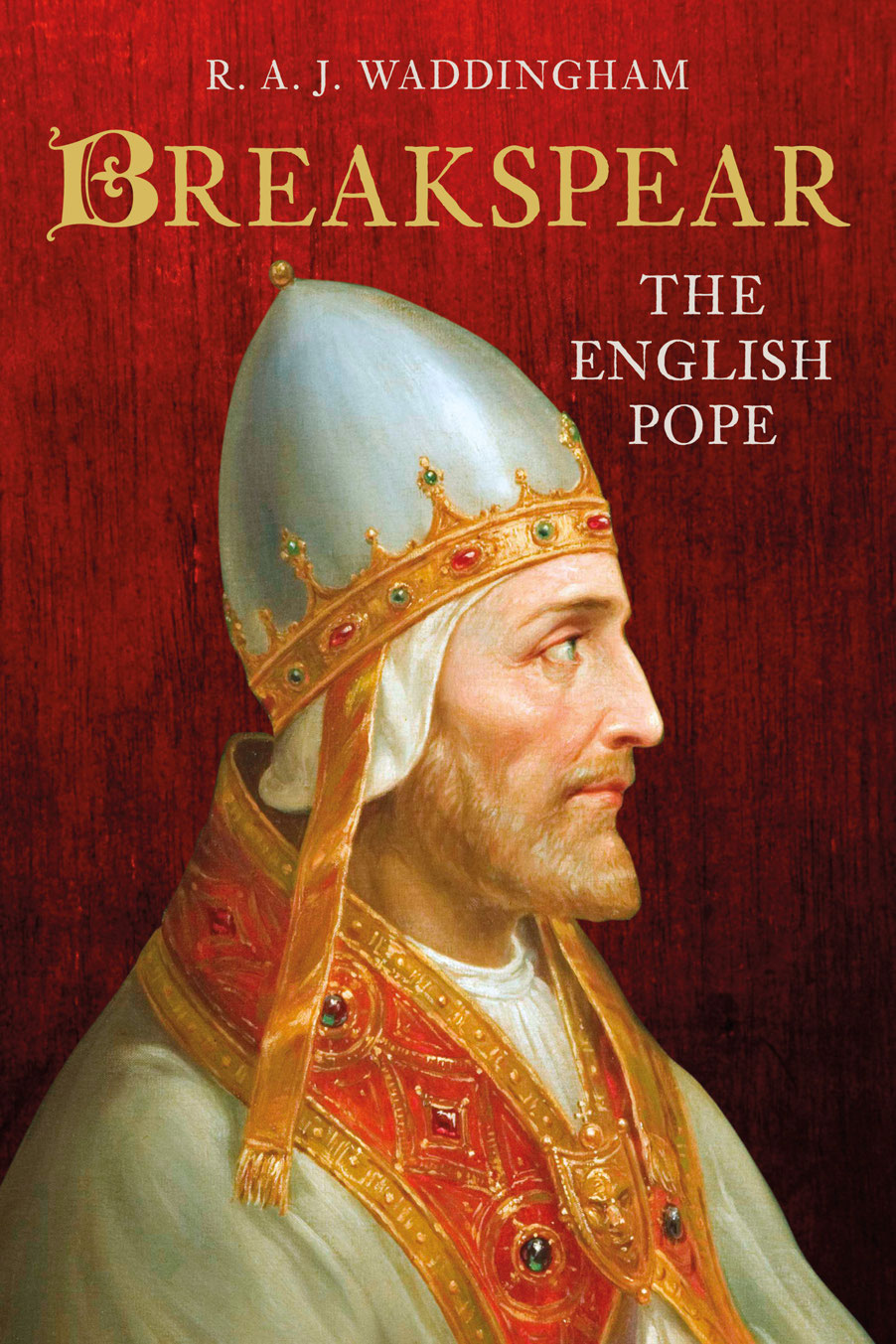

R. A. J. Waddingham - Breakspear: The English Pope

Here you can read online R. A. J. Waddingham - Breakspear: The English Pope full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Breakspear: The English Pope

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Breakspear: The English Pope: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Breakspear: The English Pope" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Breakspear: The English Pope — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Breakspear: The English Pope" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

R.A.J. Waddingham, 2022

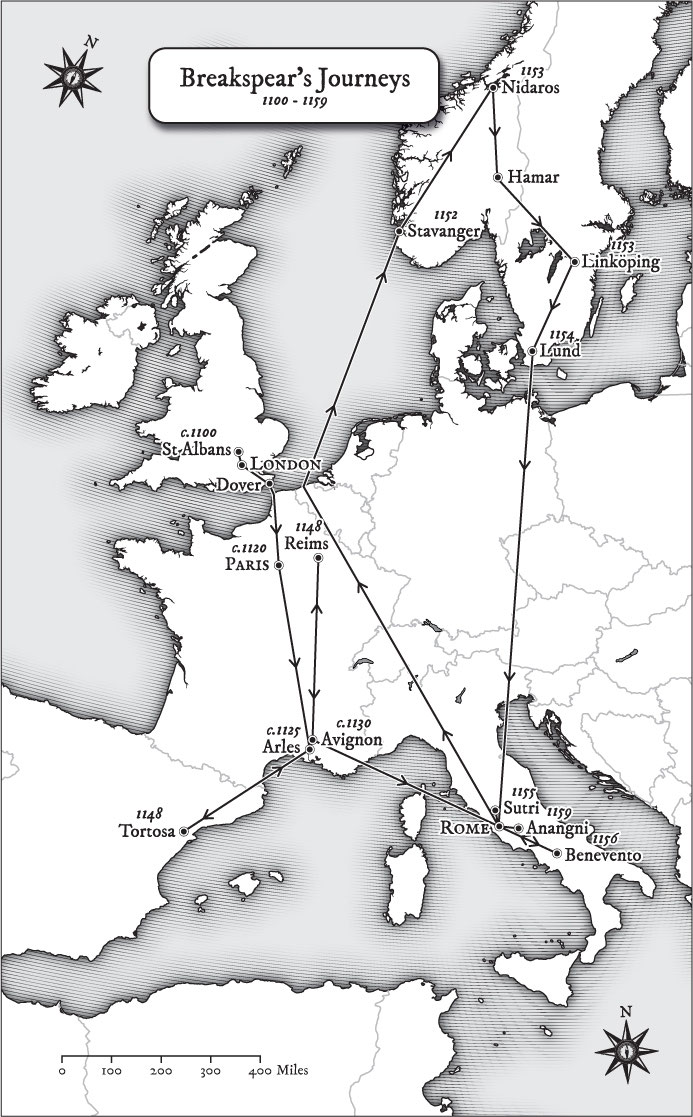

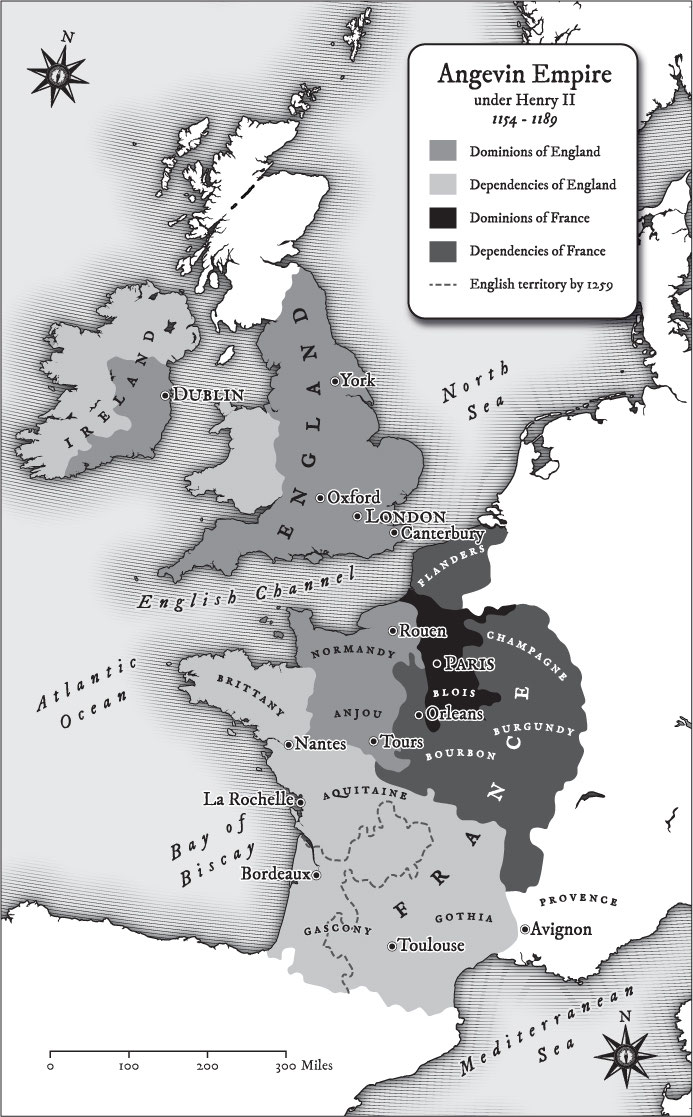

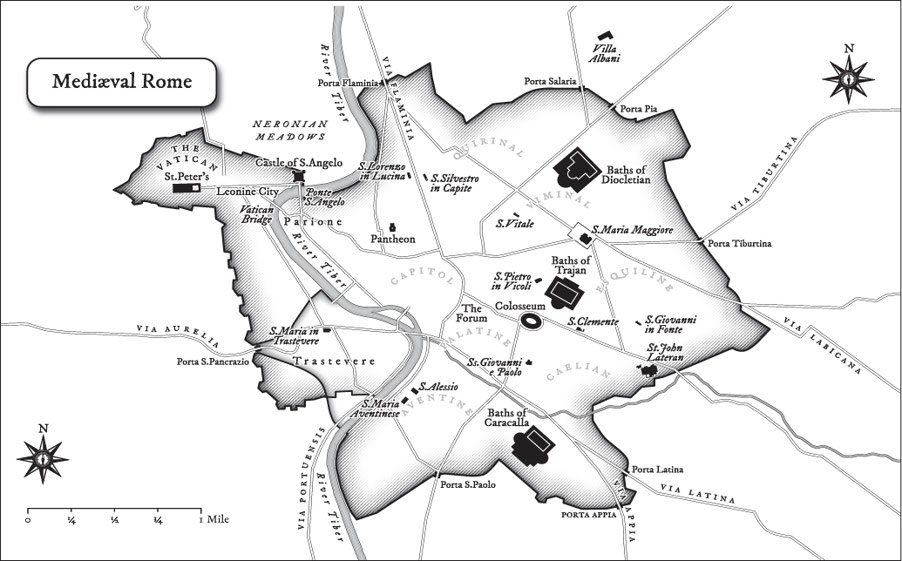

Maps FourPoint Mapping

The right of R.A.J. Waddingham to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9141 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Breakspears journeys 110059. This map depicts modern borders.

Twelfth-century England and France.

Twelfth-century Italy and the Mediterranean.

Rome in the twelfth century.

The English reader may consult the Biographia Britannica for Adrian IV but our own writers have added nothing to the fame or merits of their countryman.

Edward Gibbon1

Nicholas Breakspear was elected pope in 1154, choosing Adrian as his papal name. He is the first and so far only Englishman to sit on the Throne of St Peter. To be elected pope is an achievement at any time; to have been elected at a time when all of Europe, sovereigns included, were in thrall to the papacy is doubly so. That such an honour could fall to an Englishman of low birth is almost unbelievable. Nicholas Breakspear, born near Abbots Langley early in the twelfth century, perhaps around 1105 and probably illegitimate, was elected pope unanimously by the cardinals. Despite this great accolade, his fellow countrymen seem to have completely forgotten him: Gibbon wrote his complaint in 1789 and little has changed since. Apart from a seventy-eight-page cameo by Simon Webb in 2016 and a collection of most helpful academic essays edited by Brenda Bolton and Anne J. Duggan in 2003, there has been no biography of Breakspear published since that by Edith Almedingen in 1925.2

Most English people know about Thomas Becket, the murdered Archbishop of Canterbury, born in London to a minor Norman knight only a few years after Breakspear. Yet few in England today know anything about Nicholas Breakspear even though his story is the more remarkable. London abounds with monuments to Englands famous sons, but the capital has neither plaque nor statue to commemorate Breakspear. His familys descendants are better known in England for brewing beer. The Brakspear Brewery was established by distant relations in Oxfordshire in 1711 and to this day its logo is a bee, copied from Pope Adrians seal. They appreciate the greatness of their ancestor even if the rest of England has failed to acknowledge him.

Bishop Louis Casartelli, an Edwardian biographer of Breakspear, wrote in 1905:

It is not easy to account for the comparative neglect into which the memory of this really great Englishman and great Pope has fallen among us.3

There are reasons. Becket achieved what he did within England, whereas Breakspear spent but few years in his home country and as an adult was out of Englands sight. Beckets exciting story centred on his quarrel with the English King Henry II, and his dramatic murder when armed knights stormed into Canterbury Cathedral. This English political story stole the limelight while Breakspear was left unnoticed over in Italy, where he was apparently just doing mundane churchy things. His activities in another country could not compete with a gory murder on peoples doorsteps.

British interest in happenings in wider Europe started only much later when adventurism began, and the seeds of empire were being sown. Even then, British universities, the source of most of our historical research, remained focused on events directly involving Britain. British giants on the world stage were kings, soldiers and, later, colonialists. Breakspear was none of these, so even in these later years, he continued to be overlooked. Nonetheless, the pope was supremely powerful in the twelfth century when Christianity was the beating pulse throughout the western world. There were heresies from time to time, but these concerned the interpretation of faith rather than challenging Christianity itself. The pope had temporal power too, although much less than Germany, France, England or Spain, whose kings nonetheless all recognised the spiritual leadership of the pope. In an age when the powers of Church and state were intertwined, the popes support for a nations political endeavours was crucial. William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066 with full papal support. Even the mighty Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of Germany, intent on re-establishing the lapsed authority of the Roman Empire within Italy, craved papal support. He was desperate to strengthen his position in Germany by being crowned by Pope Adrian in Rome. King William I of Sicily had defeated Pope Adrians forces in battle but he still gave him generous terms in return for papal recognition of his kingship. Despite being greatly respected by his powerful peers abroad, English historians failed to recognise Pope Adrians importance or seek to scrutinise his life.

That Pope Adrian had to stand up to the powerful Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and that Adrians reign lasted but five years whereas Frederick dominated Europe for thirty-five years, left Adrian vulnerable to after-the-event imperial propaganda. With no sympathetic historians to champion Adrians cause or balance the story, German historians were free to belittle Adrians achievements unchallenged and unfairly accuse him of deliberately sabotaging the close links between empire and papacy. Furthermore, the papal schism on Adrians death in 1159 clouded judgements. The full story has not been fairly told.

Perhaps Pope Adrian received less attention because, by the time writers from the eighteenth century onwards began analysing history, Breakspears memory was suppressed along with the Roman Church. Breakspear was a devout churchman but his legacy is not one of liturgy, or of the minutiae of canon law, and his exclusion is unwarranted. Adrian was one of the twelfth-century popes who exercised the most influence in the political affairs of Europe, leading armies into battle and making and un-making states and their rulers. Despite a schism, he handed the papacy on to his successor in better shape than he had found it. His political power tempered by strong integrity contrasts sharply with our age, when many politicians are seen to be unscrupulous. In 1896 the Manchester Guardian acknowledged Adrians power:

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Breakspear: The English Pope»

Look at similar books to Breakspear: The English Pope. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Breakspear: The English Pope and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.