Henry, Earl of Richmond at the Battle of Bosworth, a fanciful mid-Victorian representation.

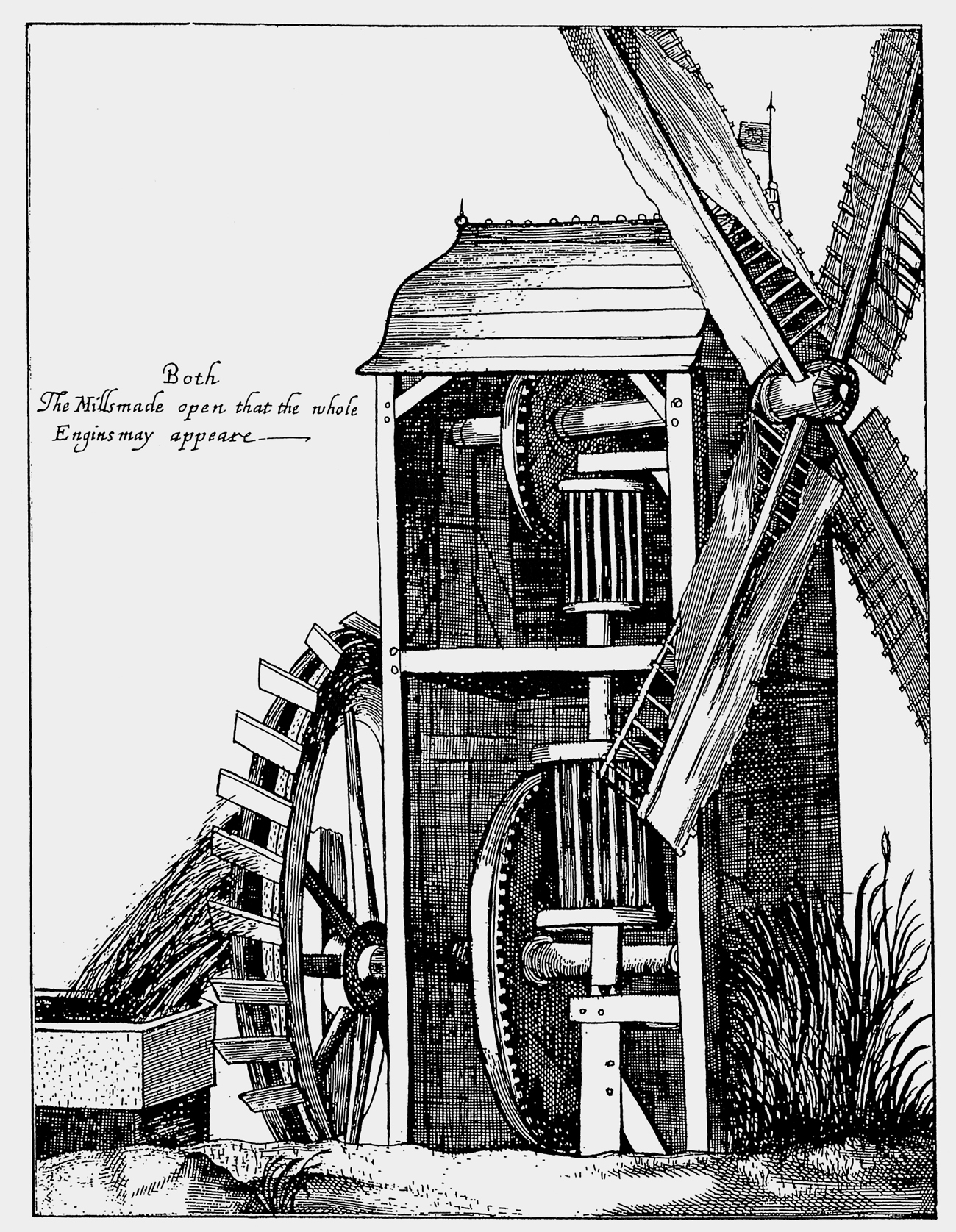

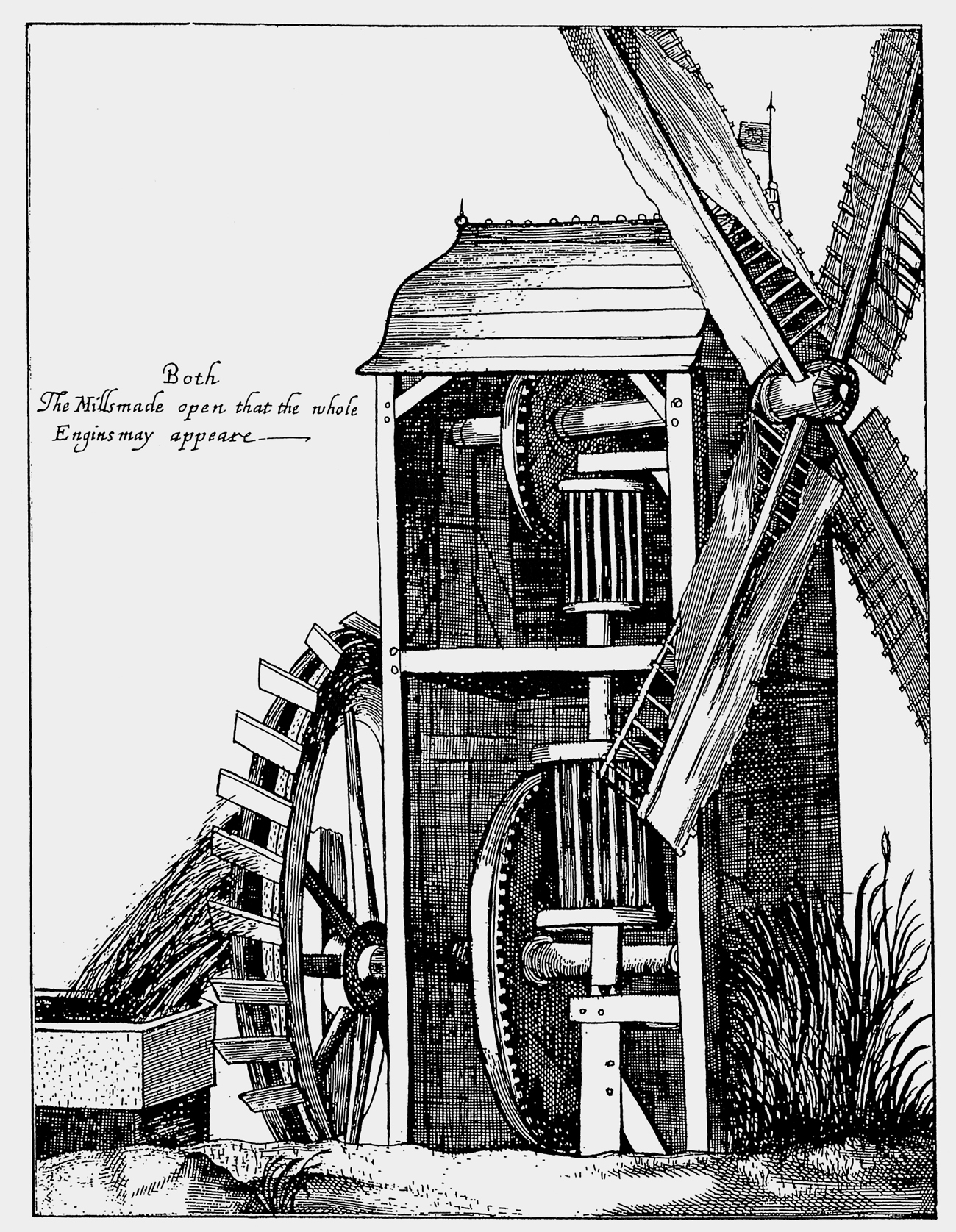

Diagram of a windmill from The English Improver Improved, 1652.

British sailor and Algerian pirate, c. 1815.

Arms of the Bedford Level Corporation, 1706.

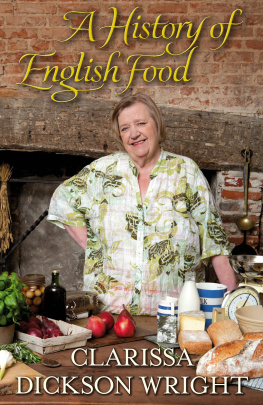

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

Histories of Nations

Knight: The Medieval Warriors (Unofficial) Manual

Shakespeares London on Five Groats a Day

A Writers Britain

CONTENTS

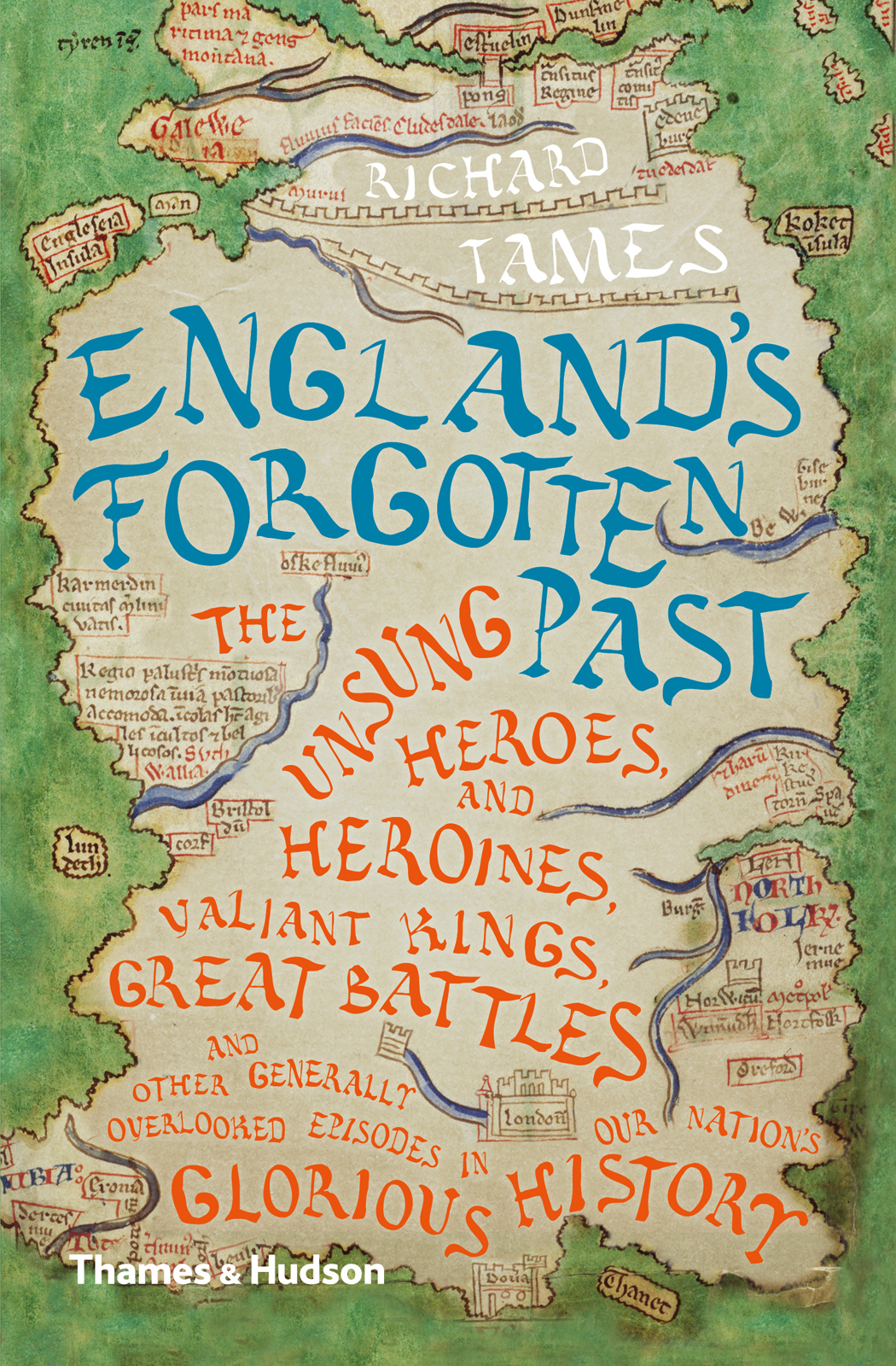

This book is about aspects of Englands past that seem to have slipped off the radar of collective memory. Some, like monarchy, the empire, religion and the origins of English identity, are now regarded by many as embarrassing, boring, trivial, marginal or irrelevant. Others, like the history of food or the landscape, have only very recently been recognized as part of proper history.

The inscription on the plinth of the statue of General Havelock in Trafalgar Square proclaims: Soldiers! Your labours, your privations, your sufferings and your valour will not be forgotten by a grateful country. But they have been.

There are a dozen streets in London alone named after Havelock, as well as towns in Ontario and North Carolina, an industrial estate in Singapore, an island in the Indian Ocean, a mid-Victorian hotel in Adelaide, a mine in Swaziland and a seaside village in New Zealand. But could one passer-by in a hundred now say who he was or what he did to merit a memorial at Londons very heart?

There is no entry for Tangier in the Oxford Companion to British History, yet Charles II spent 20 years and 2,000,000 about three times what it cost to build St Pauls Cathedral trying to establish a naval base there. It is as though it never happened.

The entry for the Northumbrian Lindisfarne Gospels in the Encyclopaedia Britannica runs to just 56 words and fails to note that they represent the first example of Christian scripture written in English.

Although England and the English represent the central focus of this book, it treats them both as somewhat permeable notions, fuzzy at the edges. Hoisting his famous signal that England expects that every man will do his duty, Nelson must have been aware that only about half the men under his command were actually English.

The empire, like the navy, was British and in both the Scots, Welsh and Irish played prominent, often eminent, parts. However, the values, institutions and lifestyles that empire represented and propagated were predominantly English. Hence the casual way in which throughout the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries the terms Britain and England were used interchangeably much as they are by many people in other countries to this day.

It is a paradox of globalization that it has sharpened the sense of distinctiveness of many national and ethnic groups, with both positive and negative effects, ranging from the vigorous revival of the Welsh language to the brutal break-up of former Yugoslavia. The reactions of the English have been confused. On the one hand, the St Georges flag has increasingly come to replace the Union flag on sporting occasions. On the other, a substantial minority still dont know when St Georges Day is.

If the English cant remember who they were they run the risk of not knowing who they are. Perhaps a rummage around in the cluttered attic of Englands past might be helpful or, at least, entertaining.

St George has enjoyed widespread and enduring popularity in England since the Middle Ages this image is taken from a fifteenth-century manuscript but how did this Roman soldier become so integral to our countrys self-image?

The knowledge of past eventsforms a main distinction between brutes and rational creatures, for brutes do not knowabout their origins, their race and the events and happenings in their native lands.

HENRY OF HUNTINGDON, HISTORIA ANGLORUM, c. 1130

Americans have an annual holiday to mark when their nation began. The English have largely forgotten how theirs did. English history conventionally began with the Romans and English kings were named and numbered only from the Norman Conquest onwards.

The period between the Romans and the Normans has pretty much vanished from popular remembrance, largely ignored in the classroom and with the exception of King Arthur (whoever he was) apparently of no interest to the makers of movies.

Yet the Anglo-Saxon centuries established the basic institutions that have shaped the nations life ever since its language and its laws, its religion and its monarchy. From pennies and parishes to acres and aldermen, the Anglo-Saxon imprint still survives today.

MADE BY INVADERS?

Traditionally, school history ignored the Ancient Britons, even though they were here first. DNA analysis now implies that they never went away and that a far higher proportion of todays population than was ever imagined may in fact be descended from them.

Successive influxes of Jews, Flemings, Dutch, Huguenots, Italians, Germans and Irish were likewise overlooked. Henrietta Marshalls Our Island Story told how Englands make-up was produced by successive invasions Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking and Norman. But each was quite different from the others both in its character and its effects.

WHATS THIS PLACE CALLED?

The first known account of the British Isles was written by Pytheas of Marseilles, a Greek, in the late fourth century BC. He called its people Pritani, probably meaning painted people. Caesar and later Latin authors wrote this as Brittani hence Britannia for their home and the name of the new province.

Next page