This edition is published by BORODINO BOOKS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books borodinobooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

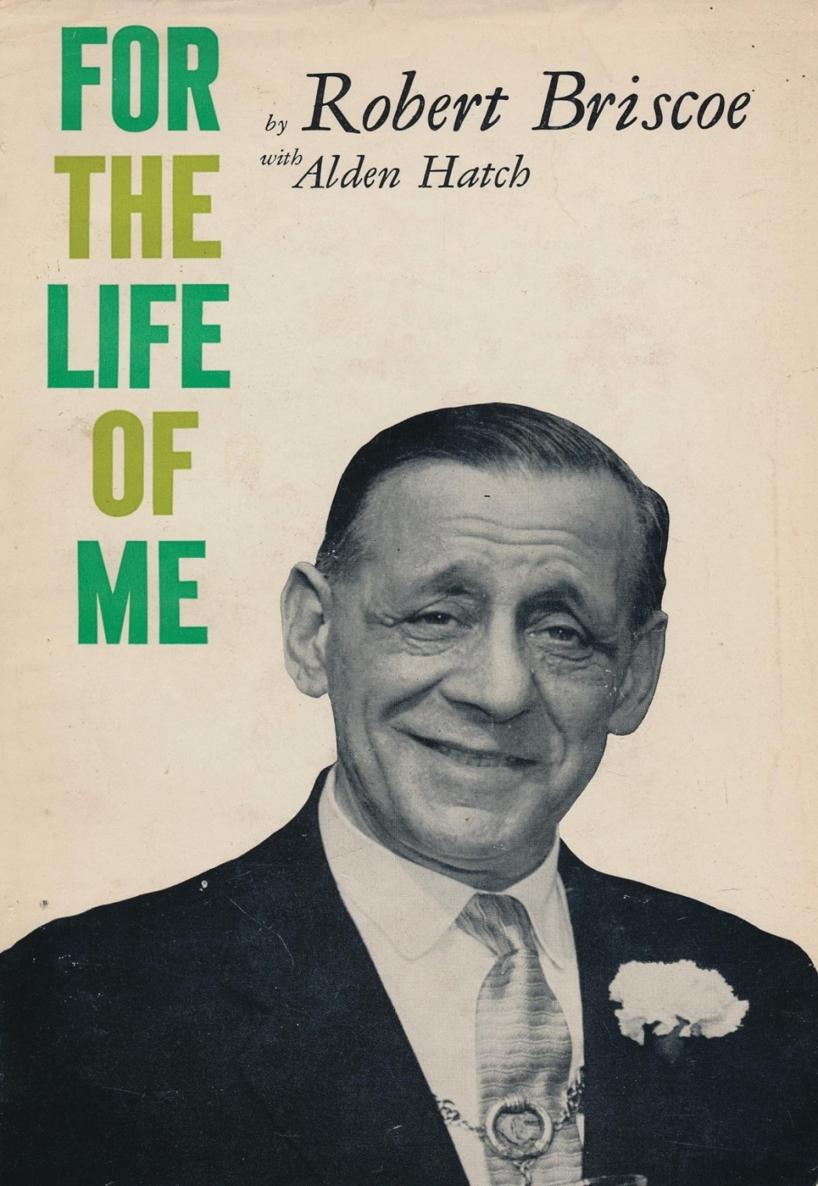

Text originally published in 1958 under the same title.

Borodino Books 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

FOR THE LIFE OF ME

BY

ROBERT BRISCOE

WITH

ALDEN HATCH

CHAPTER IAgainst the Odds

DICK WHITTINGTON, the poor country street urchin who rose to prominence and fortune, was the most famous Lord Mayor ever. I do not expect to rival him; though I have achieved a certain notoriety by the accidental fact that I became the first Jewish Lord Mayor of Dublin. But this I can say for certain. Dicks chances of achieving the great position he held were in the beginning no dimmer than mine; and I believe the road he traveled was less perilous.

For however difficult the conditions of Dicks rise, at no time were the British Army, and the Royal Navy chasing him. Nor did his own countrymen turn against him as mine did when the Free State Government ordered that I be taken, not as is customary dead or alive; they only wanted me dead.

Of all the narrow escapes I had, the closest was the day the Staters had me in their hands and let me slip through their fingers. It was near the beginning of our civil war, which, in the way of such things was even more lacking in civility than our fight for freedom against England. The war against the British had ended with the shameful treaty, signed under coercion in London, by which Irelands plenipotentiaries gave up the things we Republicans held most dear, our individuality as a nation and six of the nine countries of the North known as Ulster. We decided to fight for them even against our own countrymen.

That the Free State Government singled me out as such a dangerous character was a tribute I valued, for it showed they knew I had served Ireland well; but it was an uncomfortable sort of honor. The fact that they knew me so well, we having fought together these four years, made it impossible for me effectively to disguise my tall, lean body and long, broken-nosed face. For this reason, our Army Council decided that I was no further use to this underground fight for freedom. But since I knew America well, having been in business there before the Troubled Times, they decided that I could best serve Ireland there.

So I went on the run with orders to report to Republican headquarters in Cork, and then try to slip aboard a ship. I reached Cobh safely; but there I found that a Free State regiment held the road to Cork. In the Irish Republican Army you obeyed orders no matter what stood in the way. I decided to attempt to reach Cork by rowing the six or seven miles up the River Lee.

I stole a rowing boat and began pulling up the estuary with the long, slow fishermans stroke I had learned as a boy. The luck went against me. It was unbelievably bad. First thing, coming around a bend, I saw lying at anchor a little old rusty tramp steamer called the City of Dortmund. I recognized herand should I not! I had owned her myself and used her to run arms through the British blockade. As I came closer I saw a familiar-looking man standing on her stern whom I soon knew to be John Dowling, who had been with me in the gun-running but was now turned Stater. He recognized me, and waved and shouted amiably. Then he did a double take as he remembered that I was now his enemy. I saw him scuttle into the pilothouse and knew that my presence in the Cork area would soon be reported to Free State General Emmet Dalton, commanding there.

Around the next curve of the Lee at a place called Passage were two unpleasant surprises. A platoon of Staters were on the left bank. I slowed up my stroke and tried to act nonchalant, but they decided they wanted to talk to me. Their way of inviting me over for a chat was to start firing just over my head.

Now came the second surprise. A squad of the Irish Republican Army showed up on the right bank. I found out later that they were commanded by my good friend Martin Corry, but it did not help me then. They, too, invited me ashore by shooting in front of me. Then both sides began shooting at each other, with me underneath a bee swarm of singing bullets. I shipped my oars and lay flat in the boat with my nose pressed on her dirty bottom. While those fellows were busy with each other my boat drifted back around the bend.

Sensibly, I decided that the water route to Cork was impracticable, and rowed back to Cobh. There I hid out in Carrolls Hotel, an obscure little place. I managed to contact a girl working in a chemists shop who belonged to Cumann na mBanthe womens auxiliary of the I.R.A.and sent a message by her to the MacSwineys in Cork.

During the night the Free State troops took Cobh. In the morning I got word that General Dalton had ordered a search for me, and I knew I had better move fast.

I was just coming out of my room when two troopers closed in on me. They poked pistols in my belly, and I thought it was all up with Bob Briscoe. Once General Dalton saw me, there would be no such amenities as a court-martial or even waiting for sunrise. He would follow his orders to shoot me on sight.

Of course, I tried one last desperate bluff. What do you want of me, a peaceable wool merchant of Dublin? I asked.

Were after Briscoe, one of them said. You fit his description.

That doesnt make me him, I argued. Im just quietly doing me business.

Come along and tell it to the general!

Now I knew I was dead.

While they marched me down the stairs one of them looked at me very curiously. As we got to the main landing, he asked, Are you a Jewman?

Yes, I said quickly. In a great flash of hope I realized that those former friends of mine were so used to me that they had forgotten to put Jewish in my description.

The trooper said to his pal. Hold on! Hes only a Jewman. Wed be wasting our bloody time with him.

He swung back his foot, and gave me a great kick in the pants that sent me flying down the stairs and out the door.

I kept on flying into the chemists shop where the Cumann na mBan girl sheltered me at the risk of her life. And then secretly onto a ship, and to freedom.

It seems that I have never stopped flying since then. All I have become stems from the impetus of a well-applied boot.

On September 25, 1894, I was born; not that it mattered to anyone but my parents. The place was a small, little one-story house on Lower Beechwood Avenue, Ranelagh, a suburb of Dublin. This house still stands in a solid row of others like it; but it has no particular meaning for me, because my father moved out of it when I was only a few months old.