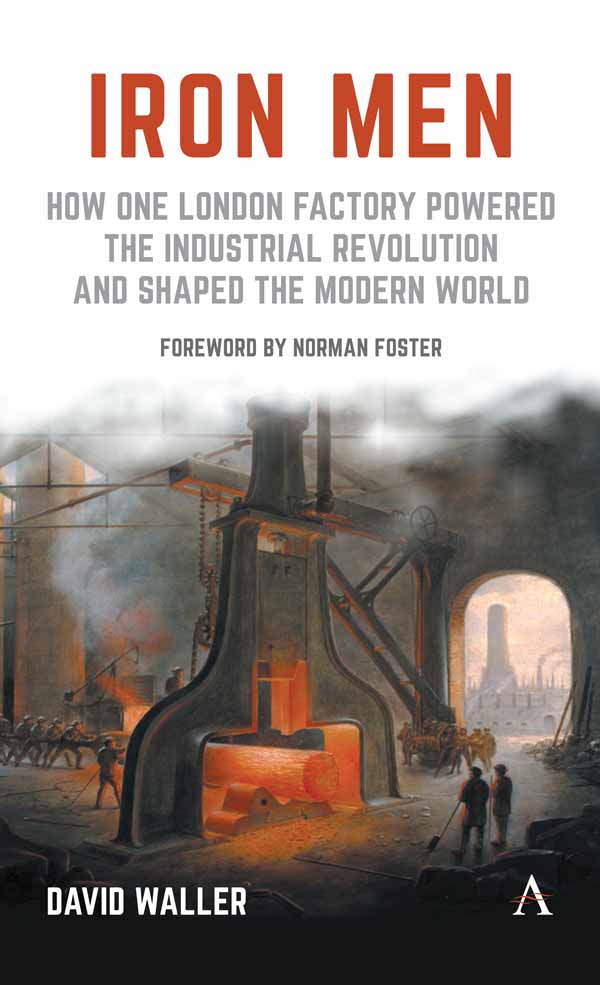

IRON MEN

IRON MEN

HOW ONE LONDON FACTORY POWERED THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND SHAPED THE MODERN WORLD

DAVID WALLER

Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.anthempress.com

This edition first published in UK and USA 2016

by ANTHEM PRESS

7576 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

David Waller 2016

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing - in - Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging - in - Publication Data

Names: Waller, David, 1962

Title: Iron men: how one London factory powered the industrial revolution and shaped the modern world / by David Waller.

Description: London, UK; New York, NY, USA: Anthem Press, an imprint of Wimbledon Publishing, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016036855 | ISBN 9781783085446 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Engineers Great Britain Biography. | Engineering Great Britain History 19th century. | Industrial revolution Great Britain.

Classification: LCC T55.8.W35 2016 | DDC 620.0092/241dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036855

ISBN-13: 978 1 78308 544 6 (Hbk)

ISBN-10: 1 78308 544 4 (Hbk)

This title is also available as an e-book.

The IRON MAN, as it has been called in Lancashire.

Andrew Ures description of Richard Robertss Sel f - Acting Mule

*

Im made of iron.

John Thornton, Victorian industrialist, in Elizabeth Gaskells North and South

Norman Foster

The Victorian era was certainly a heroic age of engineering, one of great foresight and vision that has not only shaped the cities we live in, but continues to serve as a blueprint for the future. When Joseph Bazalgette created Londons sewer system along the Thames Embankment in the late nineteenth century, he calculated the dimensions of the pipes and doubled it in anticipation of the capitals growth. Such was his prescience that those very pipes have adequately served the city till today. Even Stephensons rail track and Barlows St Pancras station have been adapted for the high-speed Eurostar that links the United Kingdom to mainland Europe, illustrating the far-sightedness of their vision a stark contrast to the short-term sticking-plaster approach all too frequently applied to many of the infrastructure projects of today.

The ultimate expression of the age was the 1851 Great Exhibition featuring Paxtons extraordinary Crystal Palace that showcased the creativity displayed by British engineers in creating machines that pushed materials and technology to their limits. Such was the variety and scale of the machinery, that they literally powered Britains transformation into the worlds leading industrial nation.

The fundamental building block of all this was standardization of machinery and parts, from the humble screw upwards, which Maudslay was instrumental in creating. Maudslays career marks the transition from craft to industrial-scale manufacturing, from water to steam power, and wood and masonry to iron (and later steel). Without the standardized components he created, mass production would have been impossible. David Waller has done us a great favour in highlighting Maudslays boundless creativity and energy and reveals him as the mentor and inspiration to a generation of talented engineers who changed the world. The picture of Maudslay that Waller paints is one of a man remarkably in tune with the most modern thinking. His workshop in Lambeth operated as a hothouse for creative engineering and a training ground for the best and the brightest more akin to a Silicon Valley start-up than an oppressive Dickensian sweatshop. His exploration of materials and their properties, and his insistence on the benefits of model-making (over 40 were produced for his block-making machines!) find an echo centuries later in present practice where 3D-printing and other traditional model-making techniques are an integral part of the design process.

Reading through the book, I found many parallels between Maudslays philosophy Keep a sharp lookout upon your materials; get rid of every pound of material you can do without; put to yourself the question [W]hat business has it to be there?, avoid complexities, and make everything as simple as possible . and that of my friend and mentor Buckminster Fuller to do more with less. Both of these visionary personalities exemplify an approach more appropriate than ever in an age of rapidly diminishing resources and environmental damage.

But perhaps most striking of all are the frequent references throughout the book to the sheer beauty of Maudslays creations a beauty born of economy of materials and pure functionality. His creations seem so perfectly fit for purpose that they take on the same qualities as most recent great works of art and design, as beautiful as a streamlined locomotive, a Chrysler Airflow, the precursor to the automobile of today, or classic and contemporary aircraft none of these would have been possible without Maudslays pioneering work.

Lord Norman Foster of Thames Bank is one of the worlds leading architects and founder of Foster + Partners, a global studio for architecture, design and engineering.

Queen Victoria could hardly keep herself away: she visited the Great Exhibition 26 times between its opening on 1 May 1851 and early August, when she departed for Balmoral and forswore further trips to the Crystal Palace. And while she was drawn to all types of exhibits, from flowers and carpets to decorations, fine arts and furnishing, cutlery and even the American Bowie knife, she seemed to be most interested in the machinery sections. Time and time again, the Queen went back to view the machines: the new cotton machinery from Oldham and Bradford; Joseph Whitworths machine tools, one of which was, as she wrote in her diary, for shearing & punching iron of just an inch thick, as if it were bread!; a knitting machine; a packing machine; a printing machine; lithographic presses; hydraulic pumps and presses; spinning and weaving machines; a curvilinear saw for timber for ships; a biscuit machine; coffee mills; a very curious machine for folding paper; a machine for making combs; an immense sugar mill constructed by Robinson and Russell of Blackwall; a new kind of ships propeller; all sorts of railway machinery and, appropriately enough, a machine for weighing sovereigns at the Bank of England.