These brief passages from works by the writer Lewis Mumford (18951990) might usefully be borne in mind while reading the pages that follow.

The cycle of the machine is now coming to an end. Man has learned much in the hard discipline and the shrewd, unflinching grasp of practical possibilities that the machine has provided in the last three centuries: but we can no more continue to live in the world of the machine than we could live successfully on the barren surface of the moon.

THE CULTURE OF CITIES (1938)

We must give as much weight to the arousal of the emotions and to the expression of moral and esthetic values as we now give to science, to invention, to practical organization. One without the other is impotent.

VALUES FOR SURVIVAL (1946)

Forget the damned motor car and build the cities for lovers and friends.

MY WORKS AND DAYS (1979)

Contents

Unless otherwise noted, all images are in the public domain.

The aim of science is not to open the door to infinite wisdom, but to set a limit to infinite error.

BERTOLT BRECHT, LIFE OF GALILEO (1939)

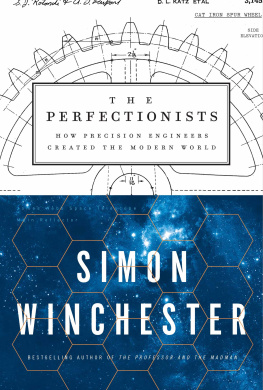

W e were just about to sit down to dinner when my father, a conspiratorial twinkle in his eye, said that he had something to show me. He opened his briefcase and from it drew a large and evidently very heavy wooden box.

It was a London winter evening in the mid-1950s, almost certainly wretched, with cold and yellowish smog. I was about ten years old, home from boarding school for the Christmas holidays. My father had come in from his factory in North London, brushing flecks of gray industrial sleet from the shoulders of his army officers greatcoat. He was standing in front of the coal fire to warm himself, his pipe between his teeth. My mother was bustling about in the kitchen, and in time she carried the dishes into the dining room.

But first there was the matter of the box.

I remember the box very well, even at this remove of more than sixty years. It was about ten inches square and three deep, about the size of a biscuit tin. It was evidently an object of some quality, well worn and cared for, and made of varnished oak. My fathers name and initials and style of address, B. A. W. WINCHESTER ESQ ., were engraved on a brass plate on the top. Just like the much humbler pinewood case in which I kept my pencils and crayons, his box had a sliding top secured with a small brass hasp, and there was a recess to allow you to open it with a single finger.

This my father did, to reveal inside a thick lining of deep red velvet with a series of wide valleys, or grooves. Firmly secured within the grooves were a large number of highly polished pieces of metal, some of them cubes, most of them rectangles, like tiny tablets, dominoes, or billets. I could see that each had a number etched in its surface, almost all the numbers preceded by or including a decimal pointnumbers such as .175 or .735 or 1.300. My father set the box down carefully and lit his pipe: the mysterious pieces, more than a hundred of them, glinted from the coal fires flames.

He took out two of the largest pieces and laid them on the linen tablecloth. My mother, rightly suspecting that, like so many of the items my father brought home from the shop floor to show me, they would be covered with a thin film of machine oil, gave a little cry of exasperation and ran back into the kitchen. She was a fastidious Belgian lady from Ghent, a woman very much of her time, and spotless linen and lace therefore meant much to her.

My father held the metal tiles out for me to inspect. He remarked that they were made of high-carbon stainless steel, or at least another alloy, with some chromium and maybe a little tungsten to render them especially hard. They were not at all magnetic, he added, and to make his point, he pushed them toward one another on the tableclothleaving a telltale oil trail to further upset my mother. He was right: the metal tiles showed no inclination to bond with each other, or to be repelled. Pick them up, my father said, take one in each hand. I took one in each palm and made as if to measure them. They were cold, heavy. They had heft, and were rather beautiful in the exactness of their making.

He then took the pieces from me and promptly placed them back on the table, one of them on top of the other. Now, he said, pick up the top one. Just the top one. And so, with one hand, I did as I was toldexcept that upon my picking up the topmost piece, the other one came along with it.

My father grinned. Pull them apart, he said. I grasped the lower piece and pulled. It would not budge. Harder, he said. I tried again. Nothing. No movement at all. The two rectangular steel tiles appeared to be stuck fast, as if they were glued or welded or had become onefor I could no longer see a line where one tile ended and the other began. It seemed as though one piece of steel had quite simply melted itself into the structure of the other. I tried again, and again.

By now I was perspiring from the effort, and my mother, back from the kitchen, was getting impatient, and so my father set his pipe aside and took off his jacket and began to dish out the food. The tiles were beside his water glass, symbols of my muscular impoverishment, my defeat. Could I have another try? I asked at dinner. No need, he said, and he picked them up and with a flick of his wrist simply slid one off the other, sideways. They came apart instantly, with ease and grace. I was openmouthed at something that, viewed from a schoolboys perspective, seemed much like magic.

No magic, my father said. All six of the sides, he explained, are just perfectly, impeccably, exactly flat. They had been machined with such precision that there were no asperities whatsoever on their surfaces that might allow air to get between and form a point of weakness. They were so perfectly flat that the molecules of their faces bonded with one another when they were joined together, and it became well-nigh impossible to break them apart from one another, though no one knows exactly why. They could only be slid apart; that was the only way. There was a word for this: wringing.

My father started to talk animatedly, excitedly, with a passionate intensity that I always liked. Metal tiles like these, he said, and with a very evident pride, are probably the most precise things that are ever made. They are called gauge blocks, or Jo blocks, after the man who invented them, Carl Edvard Johansson, and they are used for measuring things to the most extreme of tolerancesand the people who produce them work at the very summit of mechanical engineering. These are precious things, and I wanted you to see them, since they are so important to my life.