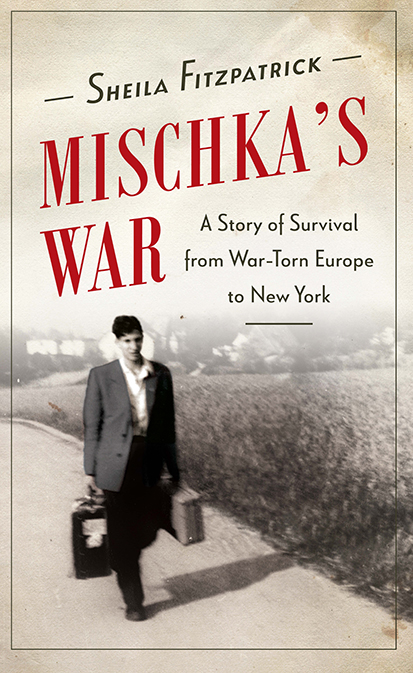

In her latest book, renowned historian Sheila Fitzpatrick recounts the remarkable wartime odyssey of Michael Danos (1922-1999), known also at various times as Mikelis/Mischa/Mischka, the theoretical physicist to whom she was married until his death. Drawing on diaries and letters, she retraces Mischkas journey from occupied Riga via a displaced persons camp to Heidelberg, where his career began to take off. Fitzpatrick does not claim that Mischkas story was representative, indeed she thinks of it as singular. Its an honest and sometimes unflinching account: we learn of his devotion to his mother, his fledgling scientific career (he regularly carried in his suitcase twenty volumes of the Zeitschrift fr Physik), his love of sport and music, and his multiple liaisons. When he and his first wife reached the USA in 1951, he proclaimed We made it. In this labour of love, Fitzpatrick shows how they did, and why it matters.

Peter Gatrell, Professor of Economic History, Manchester University and author ofThe Making of the Modern Refugee

At once tender and forensic: a beguiling combination of scholarship and love.

Anna Goldsworthy, author ofPiano Lessons

Two dramas are played out in Sheila Fitzpatricks Mischkas War: that of Misha, navigating the European catastrophe with an equanimity that often threatens to confound our understanding of it; and the authors own drama, as she tries to preserve the historians objectivity and distance from even the most terrible events, while uncovering the story of one man among the millions caught up in themthe man she met and fell in love with long after the war was over. The result is an absorbing, unsettling, rare and memorable book.

Don Watson, author ofThe Bush

Published in 2017 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2017 Sheila Fitzpatrick

The right of Sheila Fitzpatrick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

ISBN: 978 1 78831 022 2

elSBN: 978 1 78672 254 6

ePDF: 978 1 78673 254 5

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Introduction

Misha in Paris cafe, 1990.

E VERYBODY always asks me about my accent, and Misha was no exception; he thought I was Danish. It was unlike him to behave like anybody else, as I soon found out, but there are only so many pick-up lines to use on strange women on planes. At least it was better than his gently melancholy remark the next day, I must be twice your age, to which I was able to give the once-in-a-lifetime riposte: Youre 96, then? In any case, I didnt waste time on the boring answer that I was an Australian with an unplaceable hybrid accent, and batted the Danish question backwhere was he from? I thought I already knew the answer, having observed that he was writing a letter to Chre Agns and decided he was French. The Baltics, was the reply.

Which one? I asked, slightly irritated.

The middle one.

That was vintage Misha, always avoiding a direct answer, and not just because he liked to tease; he liked not releasing information, too. In a schoolmarmish tone, I informed him that, as a Soviet historian by trade, I knew which of the Baltics was which. So you speak Russian? That was great good luck, because Russian had escaped the deep freeze into which depression had put my English, though (pace Misha) English was my native language. The conversation took off at a Russian gallop before slowing abruptly as Misha switched back into English. Later he explained that he had run headlong into the second-person pronoun, which in Russian comes in either a familiar or an impersonal form: as a European born in 1922, he could not use the intimate Russian form with a woman he had just met, but as a romantic he couldnt not use it, because he was falling in love. That was vintage Misha, too, both the belief in instant intuitive knowledge and the willingness to act on it. I was temperamentally more cautious, but in this case, unlike him, I had nothing to lose. The year was 1989, annus mirabilis in the Eastern bloc.

We married and lived happily ever after, which turned out to be ten yearsby coincidence or not, the number I had bargained with God about at the beginning, for the first and only time in my life (Five years if you must, but please, if you possibly can, ten years, and Ill pay you back with ten years of mine). I should have asked for more, of course. Misha had his first stroke on 23 September 1999 and his second, the one that destroyed his brain, on the 24th. As the incumbent wife, I summoned his three children and his second wife, Vicky (who lived nearby), to the deathbed. Helga, his first wife, was in town too, looking after the grandchildren, but I didnt invite her to the hospital because she and Misha were not on good terms. None of us had dealt with a death in the family before, and Misha, a resolute denier of death in the spirit of Kingsley Amiss anti-death league, had left no instructions. We held a wake in our little cottage in Washington, DC, not far from the Potomac River and the C&O Canal that runs beside it; the guests were mainly work colleagues, physicists, like Misha. Which is the wife? I heard someone ask. In fact, all three were present.

After the wake, we had a family meeting to discuss what to do with his ashes. We thought of scattering them in the Potomac, but decided against it because of legal doubts (did one need a permit?) and some unwillingness on my part to acknowledge an American claim on him. Riga seemed the obvious alternative, consoling for his surviving brothers who still lived there, though a bit out of sync with his conspicuous lack of desire to embrace Latvia as his lost homeland. Finally, Vicky, Mishas second wife, came up with the solution: take his ashes to Riga and scatter them in the Baltic, thus giving him access to all the oceans of the world, as befitted a world citizen. Thats what we did.

After Mishas death, I got in the habit of going to his eldest child Johannas house each year for the anniversary. Johanna had the box that Misha had told me contained his mothers papers, and on the sixth year we decided to open it and look for photographs. It turned out that the papers there were not just his mothers but also Mishas, dating from the late 1930s, when Misha was an adolescent in Riga, through the 1940s and early 50s, when he and his mother were both displaced persons (DPs) in Germany before resettling in the United States. Mishas diaries were there, along with his mother Olgas diaries; correspondence between the two of them about all manner of things (news, business, music and, on Mishas part, physics, philosophy and sport); letters from Mishas brothers and old friends; official documents relating to their DP status; Mishas notebooks with physics jottings; address books; letters between Misha and Helga Heimers, the young German woman he met at the sports club in Hanover and married in 1949; as well as lots of photographs, including a whole bunch of Misha flying through the air as a pole vaulter.