First published in Great Britain in 1919 by

W. & R. Chambers Ltd, London

This edition published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Major A.H. Mure 2015

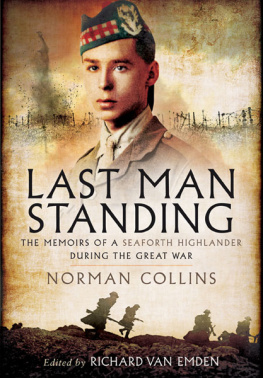

Foreword Copyright Richard van Emden 2015

ISBN: 978 1 47385 792 6

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47385 795 7

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47385 794 0

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47385 793 3

The right of Major A.H. Mure to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon,

CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction to With the Incomparable 29th

O ne hundred years on, the Allied campaign on the Gallipoli Peninsula continues to captivate the imagination of historians and the general public alike. No other Great War operation fought beyond the boundaries of the Western Front is recalled with such interest or such horror. Gallipoli has its own particular drama, for it is hard to find another campaign that was so blindly optimistic from inception and so entirely predestined to ultimate failure, as the one that took place on Turkeys south western shores between February 1915 and January 1916.

The plan got off to the worst possible start. Founded on the Allied conceit that Turks would not stand and fight to defend their own country, it was the brainchild of the persuasive yet constitutionally restless First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. His idea was to seek an alternative to the costly but necessary strategy of fighting and defeating Germany on the Western Front by attacking Turkey and defeating one of the Kaisers key allies. Yet if it was thought that this would open a convenient back door to defeating Germany, then it was illusory. Knocking Turkey out of the war, it was believed, would open up a sea route to Russias Black Sea ports, permitting the British and French to resupply their hard-pressed ally fighting on the Eastern Front. Yet the use of such a fragile supply line would hardly bring about the collapse of Germany. Churchill was fond of imaginative, broad-sweep ideas, but he was not interested in the practical detail: that was for someone else.

For the campaign to succeed, the Allies would need to press warships through the Narrows, a constricted, Turkish-controlled channel of water, before reaching the Sea of Marmara and sailing up to Constantinople. Unsurprisingly, this channel was guarded by Turkish forts and minefields and when an Allied naval bombardment failed to secure the safe passage of the warships, a decision was taken to land an Allied force to seize the high ground overlooking the Narrows. This landing force was ill-equipped, inexperienced and far from home; resupply would be difficult. To complete the task, it would have to sweep over nigh-impenetrable terrain, through dense shrub and across precipitous valleys, all undertaken in searing heat and under fire. It was the height of hubris and folly on the part of the men who ordered such a manoeuvre to think that this could be achieved. Some of the officers who fought contended that, with a little more support, a little more effort, success might have been assured, but this was utter nonsense. The infantry force which landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula in April 1915 never got more than spitting distance from the sea, penetrating but three miles inland at the furthest point. The soldiers were thirsty, hungry and with many suffering from dysentery were too ill to advance against a tenacious and motivated enemy. The Allied infantrymen merely clung to their insignificant gains of the spring and summer months until they were finally evacuated in January 1916.

Captain Albert Mure, commanding a company of the 5th Battalion The Royal Scots, a unit in the 29th Division, had come and long gone from Gallipoli by the time of the evacuation, indeed, the power of his story comes, in part, from the fact that his entire service was distilled into a mere 43 days. I say a mere 43 days, for this was far longer than many men who fought there would survive. In those few weeks, this brave, stoical officer was reduced from a fit, determined leader of men to a physical and mental wreck.

I have said in the past that I was once dubious as to the value of memoirs written during the Great War. All such personal recollections were meant to be forwarded to the Official Censor for approval so that books could be vetted prior to publication. Many, possibly most, books sent to the Censor were rejected for fear that they might give the enemy useful information as to the state of mind or the tactics of the British soldier. However, not all servicemen sent their memoirs to be subject to censorship. Some published their books and were prepared to take the consequences for ignoring a legal requirement. Nevertheless, I assumed that those memoirs that had passed the Censor would be superficial, rather too patriotic to be worth much attention. How wrong I was. Many of the best memoirs I have read in recent years were published during or directly after the war. There is a rawness and immediacy in much of the writing, a familiarity with events that could only dull over time. In short, a number of these books are worth their place amongst the many Great War memoirs. In this group I include Mures With the Incomparable 29th, a rather dull and, on first glance, opaque title that does not reflect the superb content.

Mure is a fine writer, not least because his language is simple and above all disarmingly honest honest about his own thoughts and emotions. He conveys the drama of the first landings as he watches the assault on the 29th Divisions designated beaches, and he writes evocatively of the sense of excitement and confusion as, in the distance, he sees the small figures of the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers running over a cliff, then coming back under fire. He knows that very shortly afterwards he and his men would be ashore and into the same charnel house.

He landed and witnessed the consequences of the fight to secure the beachhead. He saw too, with evident empathy, the exhaustion on the faces of the men who survived: I remarked to the assistant-beachmaster, You seem to have had a pretty thick time. He answered not a word. He only looked at me. It was enoughI turned and went away quietly, rather sheepishly. And he captures adroitly the sense of wonderment and excitement at being on land, at war and the sense of vulnerability too. I started off on a voyage of discovery along the cliff that rose abruptly behind our narrow sand-strip of beach. Before I had gone far I saw coming towards me a figure that I seemed to recognize. It turned out to be Captain Lindsay, and I was as glad to see him as if wed been foster-brothers parted for years. It is extraordinary how your heart leaps at the sight of a familiar face at the front