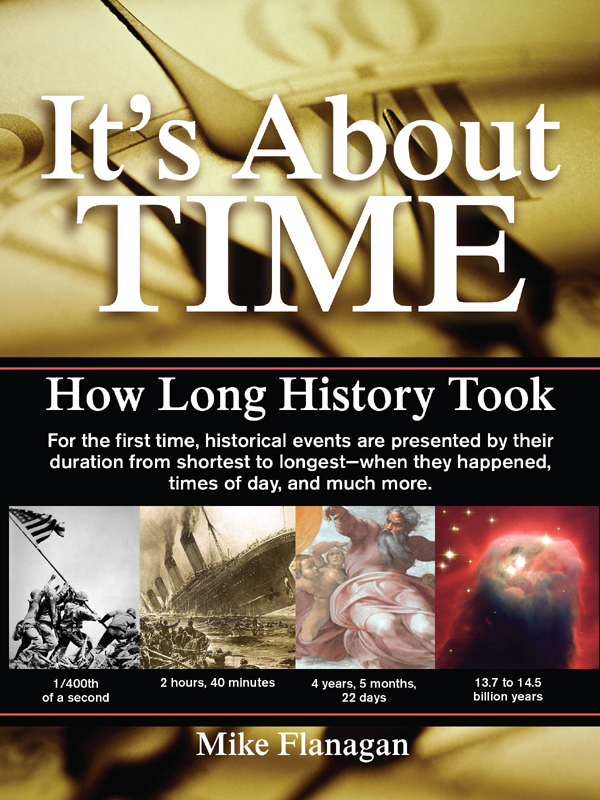

Its About Time copyright 2004 by Mike Flanagan. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information, write Andrews McMeel Publishing, an Andrews McMeel Universal company, 1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

www.andrewsmcmeel.com

Flanagan, Mike

Its about time: how long history took / Mike Flanagan.

p. cm.

E-ISBN: 978-0-7407-9297-7

1. United StatesHistoryAnecdotes. 2. World historyAnecdotes. 3. TimeHistoryAnecdotes. I. Title.

E178.6.F55 2004

973dc22

2004056044

Book design by Pete Lippincott

Cover design by Tim Lynch

Cover photo by Getty Images/Deborah Davis

Author photo by Sara Karam

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND BUSINESSES

Andrews McMeel books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchase for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write to: Special Sales Department, Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106.

For

Nancy

Time flies over us, but leaves its shadow behind.

N ATHANIEL H AWTHORNE

The Marble Faun

Introduction

T IME HAS BEEN WITH US from the beginning, invisible, untouchable, and ever present. Early people were aware of it, watching the stars gradually change their positions, experiencing the shifts of seasons, measuring their days, knowing when it was time to eat and time to sleep.

As civilizations evolved, so too did our concepts of time. The scientists believed time resided in the heavens, as sure as destiny and astrology. The mathematicians were sure it was their arena, filled with numbers and calculations. The historians knew that they were the true owners of time; how else could they record achievements as well as conflicts? And the philosophers, not to be forgotten, maintained that wisdom and experience were the true manifestations of time. The fact that we started as helpless babies, blossomed into functional adults, and then progressed into decrepitude was a cosmic message for the only animal that demanded the meaning of life.

For this book, well go along with the historian. Its about time as it relates to the durations of historical incidents, great and small. Time is a big part of history, but it often gets lost in the excitement. We have not always been able to witness history as it happens. Now that we can, we can still be fooled by time.

This collection began as a newspaper article in 1986 shortly after the Challenger disaster. Over and over, television networks kept running the all-too-quick video of the complete mission of NASAs doomed space shuttle. Start to finish, 73 seconds. Lives ended, lives changed, our collective thoughts about the commonplace safety of modern space travel got rearranged in just over a minute.

At the time, as news anchors came to grips with the tragedy and stayed on camera far into the night, they began to reflect on the JFK assassination in 1963, and how unique, personal memories would be attached to this event as well. They also talked of Pearl Harborhow history can jolt us to our very core. All this was echoed again September 11, 2001.

Working on a premise of time, I sought out the durations of a handful of other historic events, including the sinking of the Titanic, Custers trip to the Little Bighorn, and Neil Armstrongs stroll on the moon. It was fascinating putting it all together; I was often surprised by the results.

History begins in the form of news. News comes to us two ways: planned, as in a press conference or a scheduled event, and more often than not, by complete surprise. However it develops, there is always a time frame, a beginning and end. Whether it is a surprise attack, the creation of a work of art, or a conflict that took so long it was called the Hundred Years War, the element of time is always there. Even if the event might be too complex to grasp in total, we can at least identify with the impact of time.

Timing history is another matter. In the preelectronic era, a lot of the chronicling was logged in by experts who werent there. As true reporting came of age, times of day and durations become part of the stories.

How time has been calculated over the years could be a book of its own. Showing the passage of time on common calendars has always been a problem because the interval between successive vernal equinoxes is 365.2424 days. To adjust for what works out to 11 minutes less than 365 and a quarter days, the ancient Egyptians broke it down into 24-hour days, a dozen 30-day months, then added five days at the end of the year.

The Mesopotamians came up with hours and seconds, and from the Near East we got seven-day weeks. Julius Caesar decided the calendar should be based on the movement of the sun and created leap years every fourth year with 366 days. One year he also had to add two months between November and December to get the vernal equinox back to the 25th of March, and he never bothered to beware the Ides of March. But thats a different story.

In turn, he gave the odd months (first, third, fifth, seventh, ninth) 31 days and the rest 30, except for February. That was assigned 29 days in a regular year and 30 in a leap year. When Augustus came into power, he couldnt allow his month to have fewer days than Juliuss (July), so he cut a day from February and pasted it into August. Further balance trimmed September and November down to 30 days and set October and December at 31.

Things seemed fine for a while. It didnt seem to be a huge deal that the vernal equinox was lagging back one day every 130 years. By 1500, however, spring was busting out around March 10 and autumn was falling around September 13, both a little on the early side. Throwing the farmers off was one thing, but messing with Easter, which should have been taking place around Passover on the lunar Jewish calendar, was a major no-no. Jesuit mathematician Christoph Clavius got the call from Pope Gregory to fix it as soon as possible.

In 1582, things changed. The pope ordered 10 days to be dropped from October that year, which put the vernal equinox back to March 20. To fix that business of an extra day every 130 years, papal decree scratched three leap years every 400 years. This is why 1700, 1800, and 1900 were not leap years, but 1600 and 2000 were.

Working the math was one thing; getting people to accept it all was something else. Rome adopted the Gregorian calendar immediately. Germany and the Netherlands came on board within a few decades. The British, and in turn her American colonies, refused to change calendars for two and a half centuries. When the change was finally adopted, George Washington found his birthday had jumped from February 11 to February 22.

And of course other cultures around the globe such as the Aztecs, Mayas, Incas, and Chinese were measuring time by their own calendars.

For the purposes of this book, a minute is 60 seconds, an hour is 60 minutes, a day is 24 hours, and a week is seven days. One month is a calendar month, whether it took 28 or 31 days. And, a year is a year, whether it took 365 or 366 days. Now, if the incident (like the final battle of the Alamo) took place over a leap day, then, of course, that day is included.