Contents

Guide

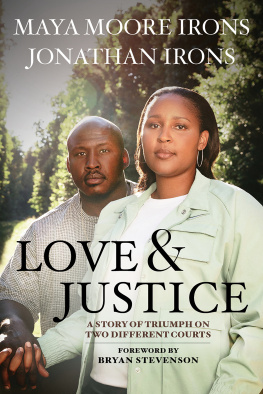

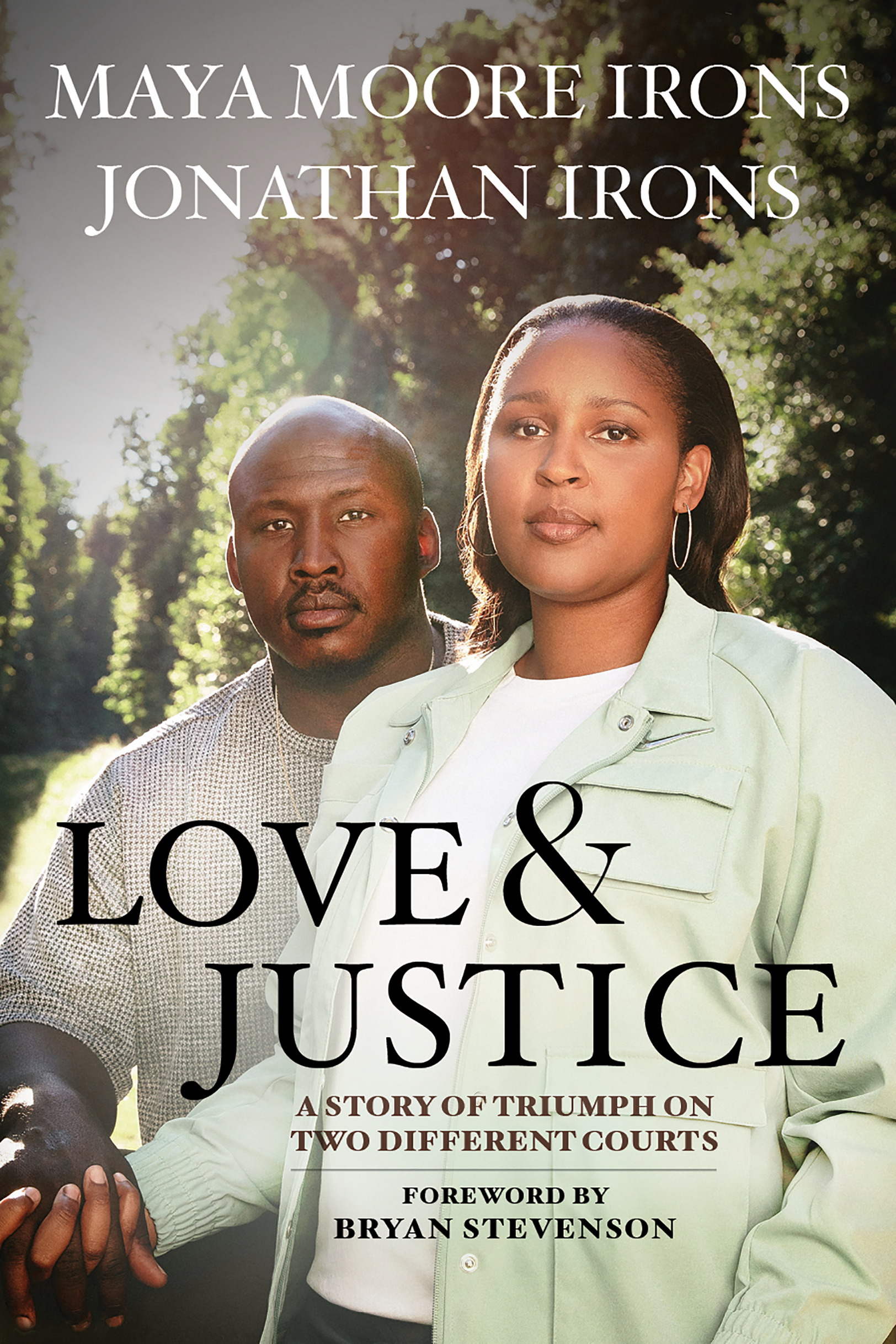

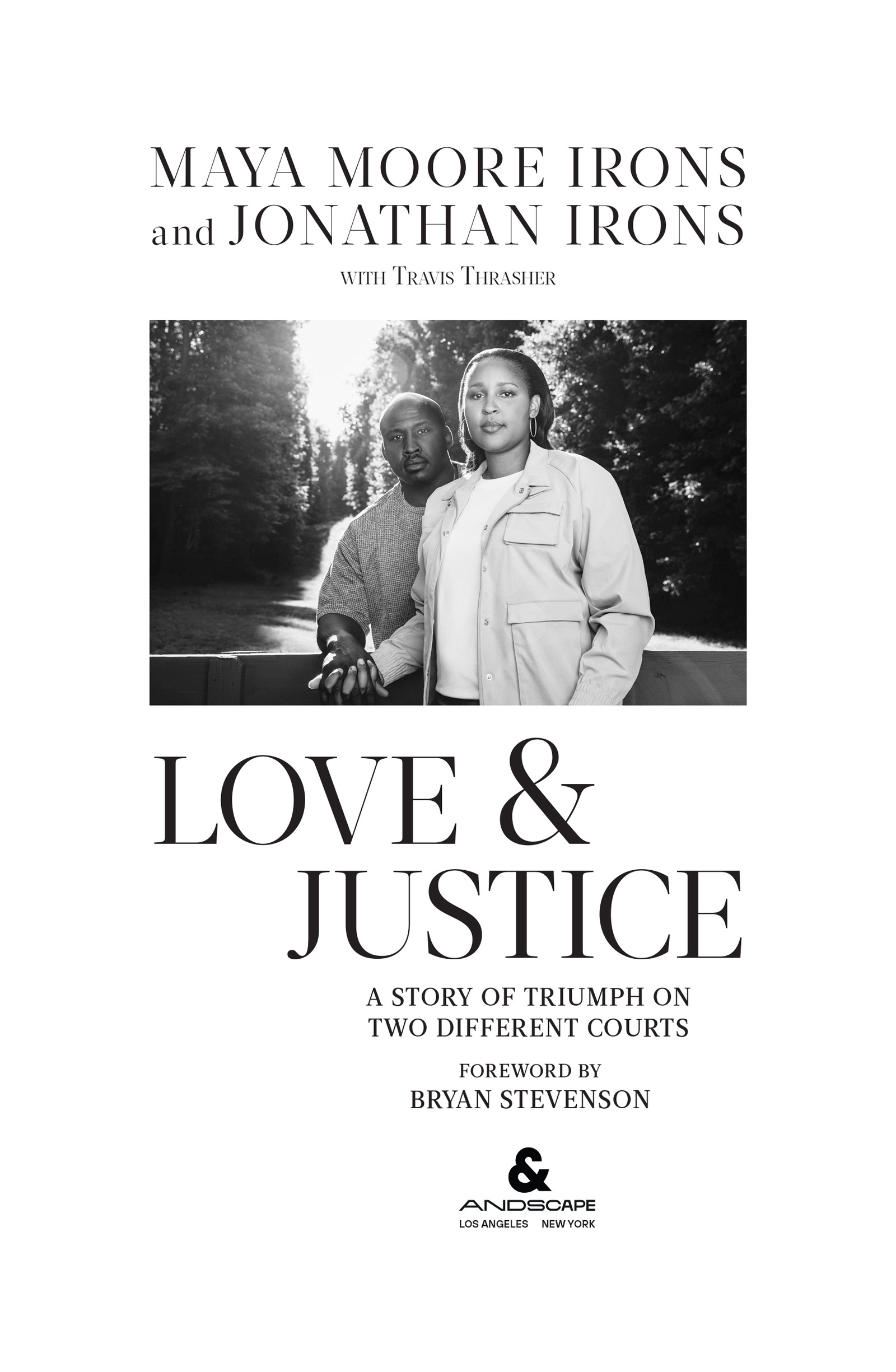

Copyright 2023 Maya Moore Irons and Jonathan Irons

Foreword copyright 2023 Bryan Stevenson

All interior photographs are courtesy of Maya Moore Irons and Jonathan Irons, except for the following:

Page iii: Copyright ESPN/Katherine & Mariel Tyler/The Tyler Twins

Page 140: Courtesy of Matt Cashmore

Page 233: Copyright 2015 NBAE (Photo by David Sherman/NBAE via Getty Images)

All rights reserved. Published by Andscape Books, an imprint of Buena Vista Books, Inc. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Andscape Books, 77 West 66th Street, New York, New York 10023.

First Edition, January 2023

Designed by Amy C. King

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Number: 2022938154

Hardcover ISBN 978-1-368-08117-7

eBook ISBN 978-1-368-09382-8

www.AndscapeBooks.com

To Granny, Papa, Cheri, and Reggie.

Your faithfulness made a way for this miracle.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

by Bryan Stevenson

IN AUGUST 2003, the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) issued a startling announcement. Based on radical changes in crime policies and sentencing laws and an unprecedented commitment to incarceration that shaped the end of the twentieth century, the bureau projected that one in three Black male babies born in the United States in the twenty-first century would spend time in jail or prison during their lifetime. One in three. The projection for Latino boys was one in six. Despite the devastating scale of this forecast, based on data and trends, very few things changed in response to this dire prediction. Government policies and practices were not reconsidered. State and federal entities did not engage in serious strategies to prevent the predicted painful futures for Black and Brown families. Most Americans, if they took notice at all, shrugged their shoulders while the United States continued to imprison its people at a higher rate than any other nation in the world.

The incarceration epidemic grew in the years that followed. The number of women in jails and prisonsmost of them mothers with minor childrenincreased 750 percent from 1980 to 2017. By the end of 2018, some 113 million American adults had immediate family members who were formerly or currently incarcerated. And by 2014, the United States, despite having less than 5 percent of the global population, held 22 percent of the people imprisoned on Earth.

At the time of the BJS forecast, fourteen-year-old Maya Moores extraordinary talent for basketball was emerging, setting her on a journey to international fame, acclaim, and achievement as one of the most dominant and successful players of her era. Two Olympic gold medals, multiple national titles at the collegiate level, multiple world championships, and MVP honors as a professional basketball player would cement her status as a sports icon and legendary superstar.

In a much less glorious space, Jonathan Irons already knew about the horrors of mass incarceration for young Black men. In 1997, six years before the BJS report, sixteen-year-old Jonathan was falsely accused of breaking into the home of a white man in Missouri who was shot by an intruder. After the shooting victim misidentified him, Jonathan was arrested, convicted by an all-white jury, and sentenced to fifty years in prison.

The case of Jonathan Irons exemplifies the many flaws in our criminal legal system. He was prosecuted as an adult in the late 1990safter elected officials in almost every state lowered the minimum age for prosecuting children as adults. Entranced by the politics of fear and anger, elected officials authorized an era of excessive punishment of children, placing kids as young as twelve in adult prisons and condemning thousands of children to decades of traumatizing confinement.

Criminologists in the 1990s falsely predicted the nation would be overrun by a juvenile crime wave, spreading fear that childrenmostly children of colorwere not really children but superpredators. New policies vilified and demonized children as policymakers built frighteningly efficient pipelines from schools to jails and prisons. The prevailing zero tolerance rhetoric was devastating for poor kids and kids of color, who were at much greater risk of arrest and excessive punishment. Jonathan Irons was one of thousands who were swept up by a harsh system that treated young people as nothing more than the crimes they were accused of committing. Today, thirteen states still have no minimum age for trying children as adults.

Jonathan Irons was not only a child wrongly prosecuted and incarcerated as an adulthe was also innocent. As Maya and Jonathans powerful story makes clear, criminal justice in America is shockingly unreliable. Over the last forty years we have invested billions of dollars to build scores of prisons around the country. State and federal governments have funded exponential spending increases for policing, prosecution, and punishment but made no corresponding investments to ensure that people living in poverty are fairly prosecuted and represented by capable lawyers. Most states do not fund indigent defense systems that can mitigate the challenges imposed on poor defendants. This imbalance has resulted in a criminal legal system that treats you better if you are rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent.

Even in capital cases, where prosecutors and courts are supposed to be more careful and outcomes more reliable, scores of innocent people have been identified on death rows across the country. For every nine people who have been executed in the United States since 1973, one innocent person has been exonerated and releaseda shocking rate of error.

Jonathans case also reveals our nations continuing failure to deal honestly with our history of racial injustice. Even after the end of slavery in 1865, the American legal system allowed white mobs to violently and lawlessly lynch thousands of Black men, women, and children with impunity for nearly one hundred years. Maya Moore and Jonathan Irons grew up in communities where Black people had been terrorized by racial violence, segregated by Jim Crow laws, and constrained by narratives of racial hierarchy for decades.

Even without a particular animus directed at him personally, Jonathan Irons was caught in a system where fairness was elusive and unjust outcomes likely. It is a grim narrative surrounded by many tragic and painful accounts of injustice and inequality.

But this book presents another side of this story.

It tells the story of how some individuals have responded to unfairness, harsh and extreme punishment, and unreliable convictions by insisting that we do better. Some Americans have refused to accept that people can only be defined by their crimesthey emphatically believe that millions of incarcerated people are not beyond hope, redemption, and rehabilitation. Like Maya Moore and Jonathan Irons, they work to embody the words of the great theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who said, Love is the motive, but justice is the instrument.

A decade after Jonathan was wrongly convicted, as Maya was leading the University of Connecticut to back-to-back undefeated, national-championship seasons, I was preparing to argue a case before the United States Supreme Court. I represented Joe Sullivan, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment without parole for a nonhomicide offense in Florida when he was just thirteen. We had argued that Joe was innocent, but the Supreme Court case was about the constitutionality of life-without-parole sentences for children convicted of nonhomicide offenses. In the companion case of