Contents

To Mike,

with my thanks and love

PREFACE

Searching for Rose

IN AN ODD way, my search for Rose ONeale Greenhow began as I was finishing a biography of a contemporary woman from a different political universe: Madeleine Korbel Albright. Secretary of State Albright had finally granted me an interview only days before the final manuscript was due. As we shook hands, Albright said to me with an impish grin: So, Ann, whom are you going to write about next?

Madam Secretary, I have no idea, I replied, returning her smile, but she will be long dead.

We laughed, not knowing the secretary had planted a seed. Soon, I had become fascinated by another prominent Washington woman who, like Albright, had lived a rich and compelling life in the nations capital and had done things few women in history even dreamed of.

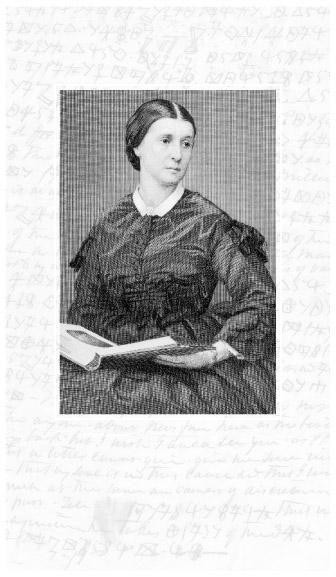

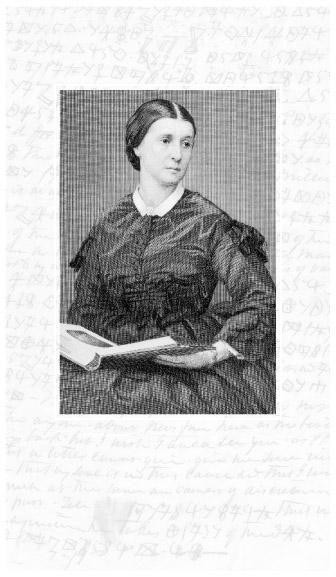

Rose Greenhow was little more than a footnote in history, a woman who spied for the Confederacy, was jailed by President Lincoln, then was exiled to the South and died a dramatic death at sea. Yet as I dug deeper and deeper, piecing together the puzzle of Roses life, a fascinating figure began to emerge, a person of nuance and complexity, with resilience and power, insecurities and vulnerabilities; a devoted wife who helped her husband negotiate Washingtons backbiting bureaucracy, and a loving mother who named three of her many children Rose until one survived to carry the name after her. She was a socialite who lived within sight of the White House and presided over elegant dinner parties, a savvy political strategist who played the odds on several presidential candidates, a handsome woman comfortable in the company of powerful mena lady not unlike Madeleine Albright, but one who lived in a time of bitter struggle that ended in civil war. Rose was a strong and independent woman who had a visceral understanding of how Washington operates, a capital obsessed with power.

For more than three decades, spanning ten presidential administrations, Rose Greenhow worked Washington society, as a hostess, a lobbyist, strategist, presidential confidante, and spy. She helped the South win the first major battle of the Civil War and thereby helped to turn an insurrection into the bloodiest conflict in American history. The secret code she used to get information to Confederate generals and the diary she kept in Europe, previously unpublished, fascinated me. Shreds of letters she tried to destroy and hints of passionate affairs with powerful men led me on a hunt through dusty archives and long-forgotten diaries. She was considered dangerous enough to have been arrested at her home by the famous detective Allan Pinkerton himself. President Lincoln had her thrown into jail. And she was probably the first American-born woman to represent a government (in this case, the Confederacy) on foreign soil.

Raised from her teenage years in a Washington boardinghouse that served as a temporary home to lawmakers when Congress was in session, Rose witnessed the unfolding of the American Republic and the growth of its young capital. Like few women of her time, she participated in the nations divisive struggles over slavery, westward expansion, and the war with Mexico. She went to California for the Gold Rush and came home through the jungles of Panama. During the Civil War, she railed against the Yankees who imprisoned her for sneaking vital military secrets to Confederate generals. President Lincoln exiled her to the South, forbidding her to return to Washington until the war was over.

In the summer of 1863, with the South desperate for help, Confederate president Jefferson Davis tapped Rose Greenhow as his personal emissary to Europe, hoping in vain to persuade the British and French to recognize the Confederate government. Rose negotiated with Napoleon III and fought for recognition of the Confederacy at the highest levels of British aristocracy and government. Prone to debilitating seasickness, she nonetheless traveled thousands of miles by ship and moved back and forth between London and Paris, talking to anyone she thought might advance the Confederate cause.

She was also a slave owner, a social climber, an elitist, and a snob. Clever, beautiful, articulate, and outspoken, Rose circulated in a society whose members, even today, are remembered as she has not been: her hero John C. Calhoun; Senators Daniel Webster, Stephen A. Douglas, and Thomas Hart Benton; Dolley Madison; Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney; John and Jessie Benton Frmont; diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut; Presidents Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, James Polk, and James Buchanan; and her Confederate correspondents Jefferson Davis and General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard.

She was a clever woman, much more clever than was ever admitted by her associates, wrote Confederate navy secretary Stephen R. Mallory after her death. She started early in life into the great world, and found in it many wild beasts; but only one to which she devoted special pursuit, and thereafter she hunted man with that resistless zeal and unfailing instinct.... She was equally at home with Ministers of State or their doorkeepers, with leaders and the led, and she had a shaft in her quiver for every defense which game might attempt and to which he was sure to succumb. 1

Some of Roses contemporariesespecially the womensnickered or sneered at her behavior. They whispered among themselves that her way with men passed through the bedroom. Rose chose not to write about her romantic life. She was, after all, a woman of tantalizing secrets, alluring if not discreet. Men loved hermarried men. They said so in breathless, passionate letters, and they undoubtedly said so when they were alone in her house, wrapped in a tight embrace long after the sun had set. And as Mallory wrote, some probably did succumb.

But there was more to Roses life than illicit love affairs. Men valued her counsel, as was evident from her correspondence with James Buchanan and the trust put in her by General Beauregard and Jefferson Davis. Few men, however, gave her more than a mention in their official papers, a familiar pattern now recognized by historians seeking to know more about the lives of women. When war came, she burned what letters and papers she had to keep them away from the Yankees.

Born on a small plantation in Montgomery County, Maryland, when the region was an integral part of the South, Rose knew heartbreak and hardship from early childhood. Her father died a violent death when she was barely old enough to know him, and his slave was arrested, convicted of his murder, and hanged. Rose and her sisters were separated and sent to live with relatives.

Like most women of that time, she had no career other than wife and mother and contented herself for years with engineering her husbands success and giving birth to a child every couple of years.

A few remarkable samples of her voice survive. She returned to California in 1857 for a celebrated fraud trial, and her testimony shows she was an exacting witness, undaunted by her male inquisitors. When she was summoned from the Union prison in Washington in 1862 by a federal commission to determine whether to try her for treason or send her south into exile, she used the hearing to blast the enemy for trampling her constitutional rights. She battled the commissioners to a verbal standstillall without a lawyer. Roses memoir of her imprisonment in Washington, published in England in 1864, lambastes her captors as murderous tyrants in her characteristic rhetorical hyperbole, but her reporting of life behind barswith her childis remarkably consistent with official records.

Next page