IMAGES

of Modern America

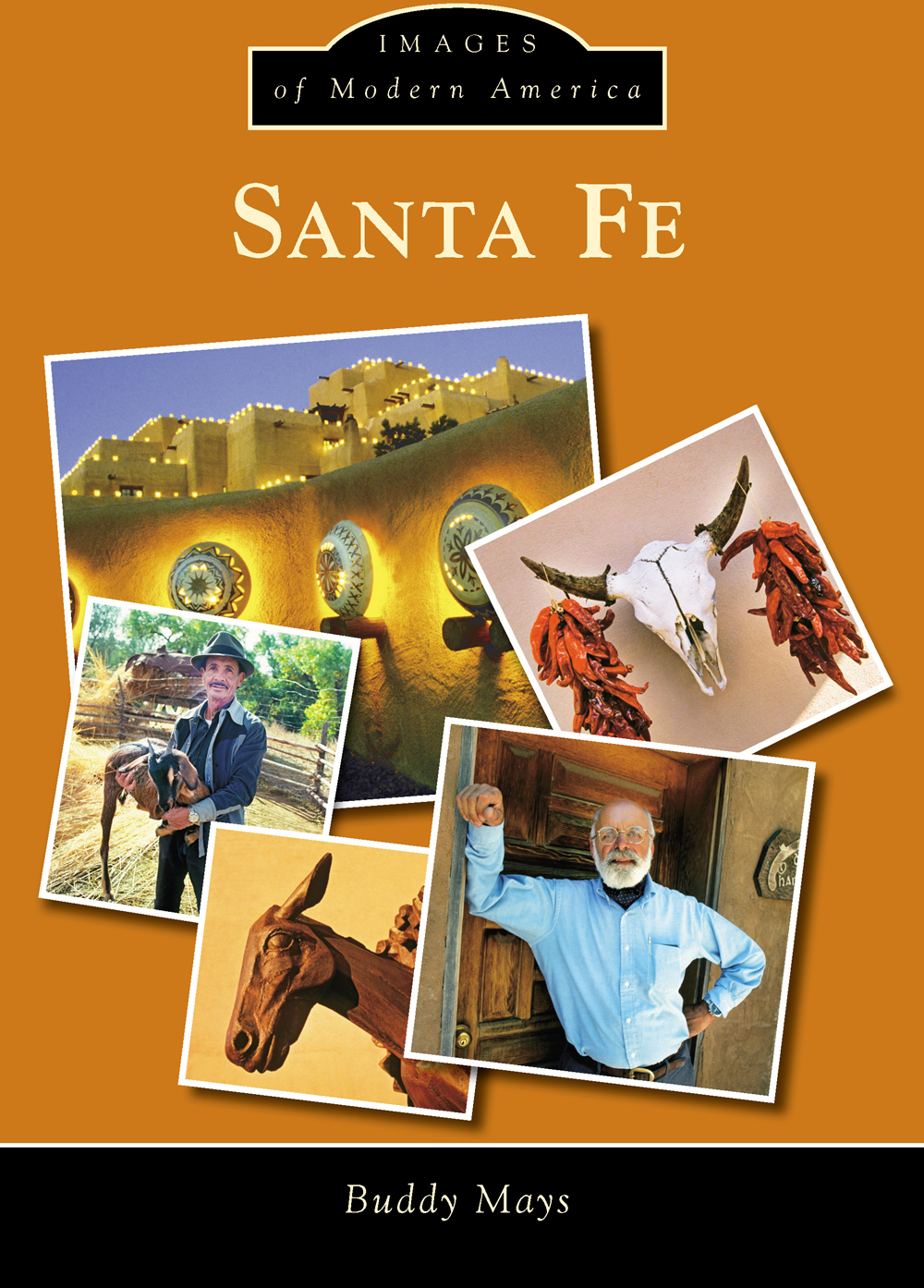

SANTA FE

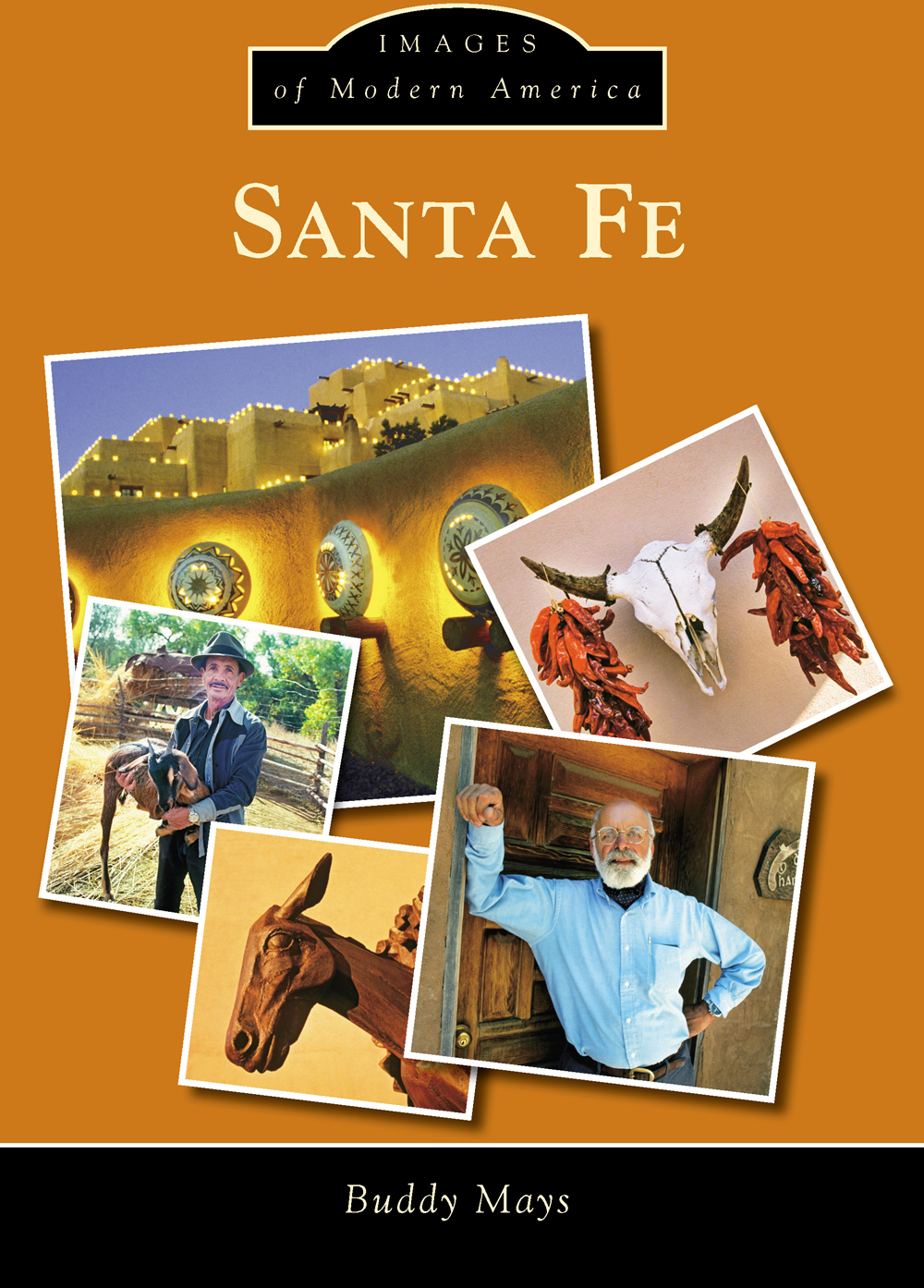

Santa Fe native Buddy Mays is a freelance lifestyle photographer and writer whose images of, and articles about, northern New Mexicos people and places have appeared in hundreds of national and international publications. He is the author of 12 previous books, including 2012s Hard to Have Heroes, a prize-winning novel about the American Southwest, and People of the Sun: Some Out-of-Fashion Southwesterners, which he coauthored with historian Marc Simmons in 1979. Mays attended New Mexico State University and is a vertebrate zoologist by education. He is also an avid hiker, skier, hunter, and fisherman, having spent much of his life enjoying the wildlife and wildland of the American Southwest.

ON THE FRONT COVER: Clockwise from top left:

Inn at Loretto on Christmas Eve (see )

ON THE BACK COVER: From left to right:

Happy Ley at the Terrero Store (see )

IMAGES

of Modern America

SANTA FE

Buddy Mays

Copyright 2015 by Buddy Mays

ISBN 978-1-4671-3312-8

Ebook ISBN 9781439650141

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014954332

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe a hefty debt of gratitude to my wife, Stephanie, for her skillful proofreading and editing assistance and to the dozens of Santa Feans who helped me research locations, check facts, and find mistakes. Special thanks as well to all of the memorable New Mexicans, living and deceased, who allowed me to take their photographs during the late 20th century. Ill be forever grateful. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are by Buddy Mays.

Hallelujah, comes the Gypsy, bring he glory to your soul But his essence begs sustaining, lay a coin inside his bowl Then hell snare your secret parable with his sword of sober truth The gnomic gleam unbearable of fleeting, tender youth

El D Odell, from Ode to Santa Fe, 1979

INTRODUCTION

Nestled in the pion-covered western foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the settlement of Santa Fe was established in 1608 by Spanish soldier Juan Martinez de Montoya. The city is one of the oldest, continuously inhabited communities built by Europeans in the United Statessurpassed in age by only St. Augustine, Florida, and Jamestown, Virginia. It is the site of the oldest public building in America, the Palace of the Governors, and the oldest church, the San Miguel Mission, both constructed about 1610. It is also home to the nations longest-running communal celebration, the Fiesta de Santa Fe, first held in 1712. The city is a world-class art and music center, providing visitors and residents with an all-season menu of activities. It is little wonder that historic Santa Fe is also New Mexicos most popular tourist destination, attracting more than one million visitors each year.

In the early 1600s, Santa Fe was a small, isolated community of soldiers, farmers, and Franciscan missionariesthe latter dedicated to converting thousands of Pueblo Indians to Christianity. Surrounding a main square or plaza, the central part of the settlement was walled and fortified against potential attack from any of two dozen nearby Indian pueblos. The colonists made two fundamental errors during Santa Fes formative years, both concerning their Indian neighbors. First, they introduced the encomienda, a system of taxation that gave government and church officials the right to extract an annual tributemostly in the form of food, human labor, or personal servicefrom each Indian household. Second, the Franciscan friars prohibited Pueblo residents from practicing their centuries-old religious ceremonies and, using forced Indian labor, erected large mission churches in almost every native community.

Most Puebloans hated both the encomienda and the Franciscan missionaries. Pueblo men and boys were forced to labor long hours in their fields to pay the tribute, while Indian women and girls working in Spanish households were often sexually abused by their masters. By 1680, the Pueblo people had endured enough. Late that summer, 2,000 angry warriors pillaged and burned much of Santa Fe, slaughtering settlers and missionaries as they went. Other war parties attacked churches, farms, and outlying communities throughout New Mexico. A combined 400 colonists and 21 Franciscan friars were slain during the first few hours of this Pueblo Revolt, and at least 2,000 others were sent scurrying south toward Mexico. The success of the uprising was short-lived, however. In 1693, just 13 years later, Spanish conquistador Don Diego de Vargas led an army of 800 soldiers, settlers, and friendly Indians back to Santa Fe and ordered the occupying Indians to surrender. They refused, and in the bloody battle that followed, the heavily armed Spaniards killed 79 warriors and sentenced every family member of the slain Indians to 10 years in slavery.

Once again under Spanish control, Santa Fe grew slowly but steadily over the next century as more colonists arrived each year from Mexico City. In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain, and Santa Fes ownership and political jurisdiction reverted to the Mexicans. That same year, American William Becknell led a string of pack mules loaded with trade goods into the Santa Fe Plaza, having journeyed all the way from Missouri on a new trade route he called the Santa Fe Trail. Becknnells arrival nudged Santa Fe out of the dark ages. Within a few years, a steady stream of wagons bearing American and European merchandise was pouring into the city, where amenity-starved residents eagerly purchased it for exorbitant prices. In 1845, the United States declared war on Mexico after 16 Americans were slain by a Mexican cavalry unit on the US side of the border. Pres. James Polk immediately ordered a large force of American soldiers to occupy Santa Fe and lay claim to the New Mexico Territory. The campaign was swift and bloodless; commanding general Stephen Kearney took the city without firing a shot and established a joint civil and military government to run the territory. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed two years later, ending the war and officially surrendering Santa Fe and New Mexico to the United States.

In 1880, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) reached the village of Lamy, 18 miles south of Santa Fe. Surveyors deemed the terrain too difficult for a main line track, so a small spur line was built that would carry passengers and freight from Lamy into the city. In the years that followed, Santa Fes population increased slightly, but the economic prosperity that residents had hoped for with the railroads arrival did not materialize. In the 1930s, however, a group of farsighted business leaders and city officials began to advocate a novel idea: tourism, not industry, was the key to an affluent future. The idea took root, and shortly thereafter, city fathers and business leaders initiated a five-decade-long cultural and architectural face-lift that aimed to transform Santa Fe into a major tourist destination.

By the late 1970s, the city was riding high, both aesthetically and economically. Santa Fe Stylea visually appealing meld of traditional Pueblo and Spanish mission architecturehad become a common catchphrase throughout the western hemisphere. Community get-togethers like the Indian Market, Spanish Market, and Fiesta de Santa Fe had been expanded into internationally acclaimed events, and Canyon Road, Santa Fes 80-year-old artist colony, had become an American mecca for art lovers and one of the worlds top art markets. The icing on the cake was the opening of the Santa Fe Opera, a world-class outdoor facility that not only attracted wealthy music aficionados but also the countrys preeminent operatic talent.

Next page