Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2022 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

and

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

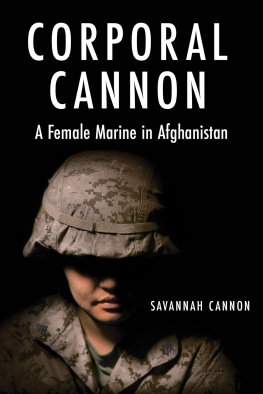

Copyright 2022 Savannah Cannon

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-166-1

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-167-8

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United States of America by Integrated Books International

Typeset in India by Lapiz Digital Services, Chennai.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

This publication has been cleared for publication by the Department of Defense. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Note from the author: I have tried to recreate events, locales, and conversations from my memories of them. In order to maintain their anonymity, in some instances I have changed the names of individuals and I may have changed some identifying characteristics and details.

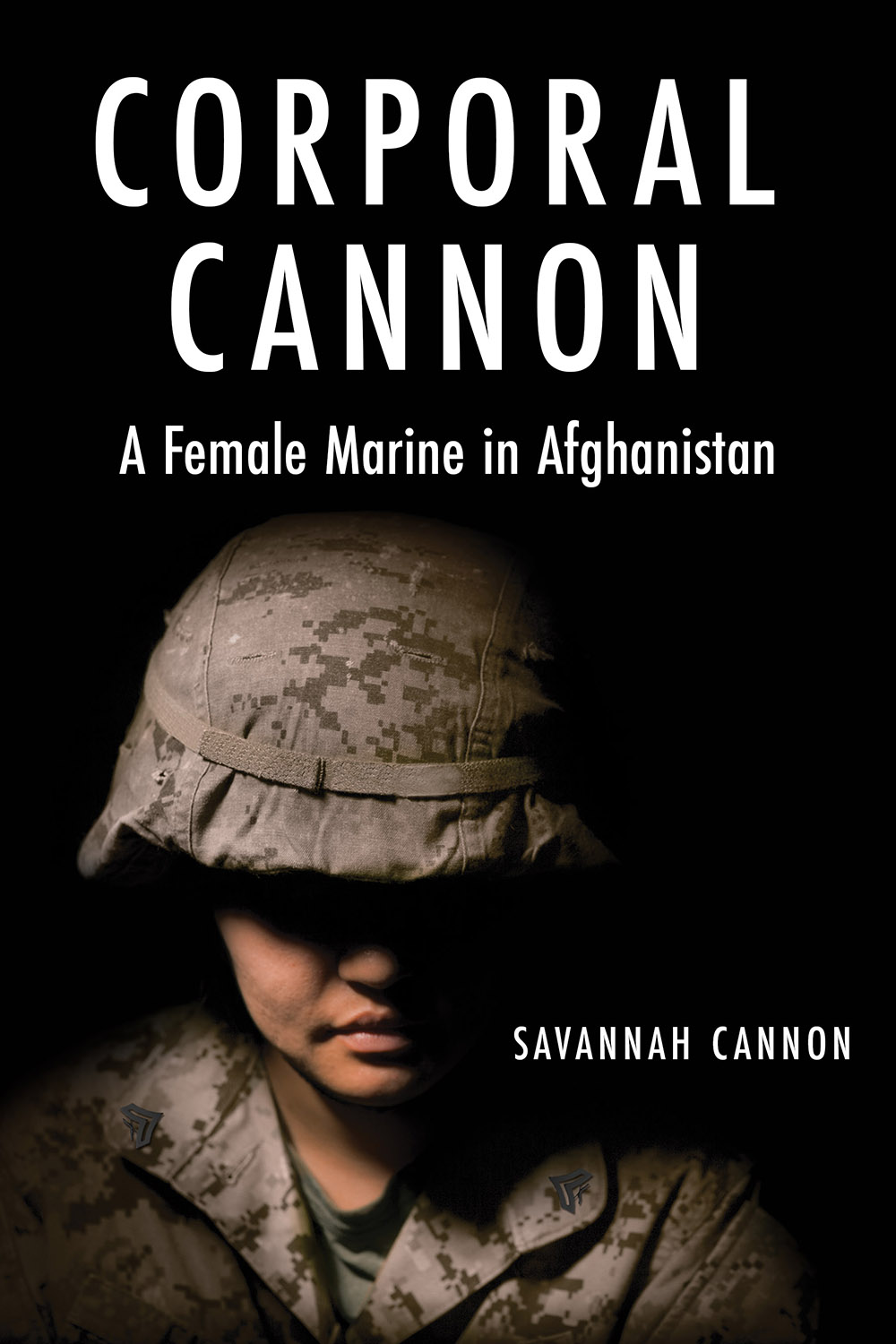

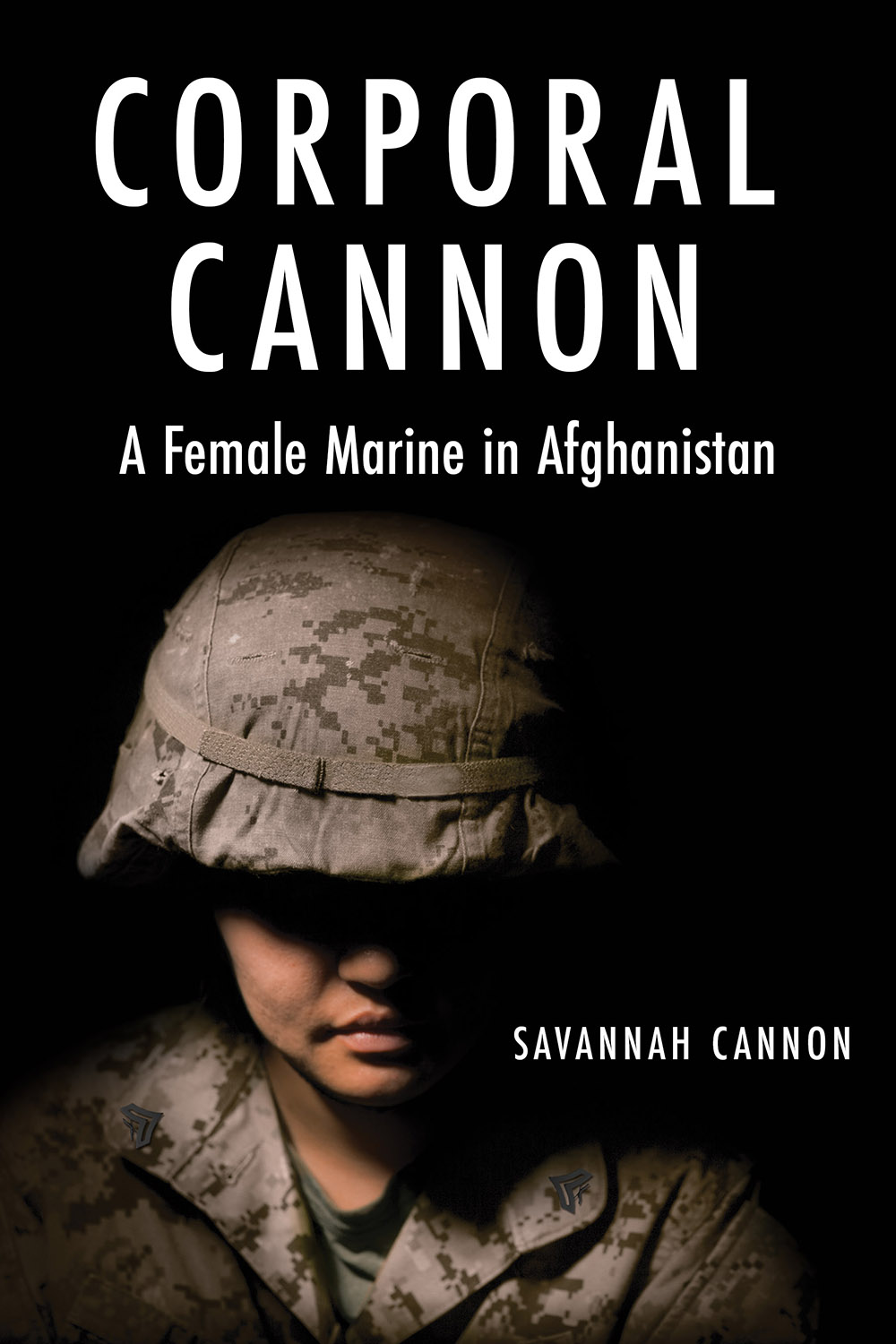

Cover image Sarah Tirza

To those who are still fighting, and to those who support them.

Contents

Foreword

2017, San Diego, California

I began writing this book largely as a form of self-therapy, one that forces the trauma victim (me) to walk through a difficult experience in as much detail as possible in a non-stressful environment.

It took me a long time and several panic attacks (one putting me in the hospital with what I thought was a heart attack) to understand that I needed help.

So, I tried to get help.

I requested PTSD help from Veterans Affairs (VA) six months ago but never heard back.

I requested help from an outside organization that took four months to get back to me, at which point I was turned off by their lack of professionalism (they had promised same-week assistance).

I requested help from my doctor who prescribed a sedative to which I eventually became addicted.

I tried talking to a therapist who said Jesus would help me if I stopped doing such horrible things. I walked out of his office.

I have lost friends to suicide. One hung himself in the garage and left three children fatherless. I have thought about swerving my car into oncoming traffic just to escape my own mind. But I have a son, and he deserves more than that.

Depression is like standing in a pitch-black room full of dangerous objects that you cannot see. You know you should move around, live life normally, but the darkness is so heavy and pain follows any action. Even fumbling around for a light switch can hurt because you may stumble into one of those dangerous objects. So, you become immobile.

People always said, Just come to me if it gets that bad. But when the pain is inside your head and radiates to your toes, no one can help.

So, in a last-ditch effort to get better and have nightmares less often, I finally understood that what I really needed to do was write.

If this story is descriptive in parts, and blank in others, it is because I wrote it as I remembered it. The language used in my account can be rough and in some places, considered offensive.

Today, I have a great life, and I am safe. But I think its time to address what happened during my Afghanistan deployment in 2010. Perhaps my words will help some of you realize that youre not alone in your pain; that you can also get better.

August 2010, Camp Delaram, Afghanistan

I stepped into the tent and walked across the dusty floor to my bunk. My boots left imprints in the sand, so fine that they looked and felt like moon dust. No matter how often I swept, the desert always came back.

My bunk bed was in the back-left corner of an empty tent that was designed to hold over 30 bunks. The tents were giant containers shaped like soup cans that had been cut in half vertically and turned with the cut side on the ground. The metal frame was covered in a sandy-colored canvas designed to protect its inhabitants from the sun and other elements. The canvas did nothing to protect us from mortars.

I slept in the same tent as the only other female Marine at Delaram, Lance Corporal Sandwith. Her bunk was in the back also, and we had both hung extra sheets from our top bunks to enclose our sleeping areas on the bottom. Not that it matteredwe never saw each other. She and I were doing different jobs, saw different people, slept at separate timesif we did sleepand patrolled different bases with different enemies.

I took off my rifle and sat down on the bed. A blank wall stared back at me. Everything was the same color as the deserta weird yellow-tan; even things that werent that color were covered in the powdery sand and eventually melted into the never-ending landscape. I Googled pictures of fields when I was at work just to see some green.

Sweat dripped from my face. If I sat too close to the edge of the tent, the canvas radiated 140-degree heat from outside. But the edge of the tent was also where the air-conditioning tube ran, which blew sometimes-cooler-than-140-degree air. I say 140 degrees because after 120 degrees, does it even matter how hot it really is? It was August, in the Middle Eastern desert, with no natural shade; it felt like Satans asshole.

Gazing listlessly at the wall, I fumbled for the 30-round magazine I kept in the right cargo pocket of my cammie bottoms, on my calf. We had to have ammo on us at all times, and since we werent supposed to have our rifles loaded on base, most people kept their cartridges in that pocket. As I pulled the mag out, I looked at the scrape marks on the cartridge from the constant insertion and retraction that we practiced. The portion of the mag that had been scraped was a shiny, silvery color; the rest of it was black.

Flipping the mag around in my hands a few times, I felt the familiar weight of 30 bullets. I picked my rifle off the ground and inserted the magazine.

With a firm pull, I racked back the rifles charging handle. It slid forward, and the bullet moved into place. I knew that when I pulled the trigger, the bullet would travel up through the chamber and meet its target. The mag would be lighter than usual to the person who picked up my rifle, and the casing for that bullet would be cast to the side, falling under my gear until the staff non-commissioned officer who would inventory my personal effects found it.

After flipping the rifles safety from SAFE to SEMI with a quick snap, I gently placed the buttstock of the rifle between my legs and onto the ground. I slid both of my hands around the top of the barrel. As my right hand slid down the rifle and toward the trigger, I felt the dust scrape against my fingers on the ridged plastic and metal.

Next page