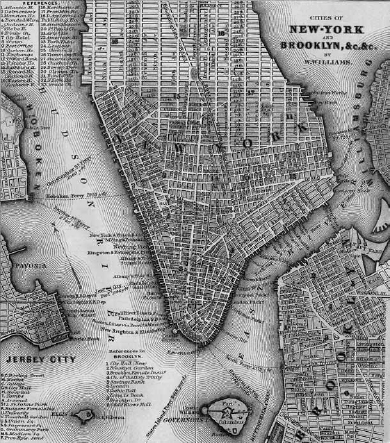

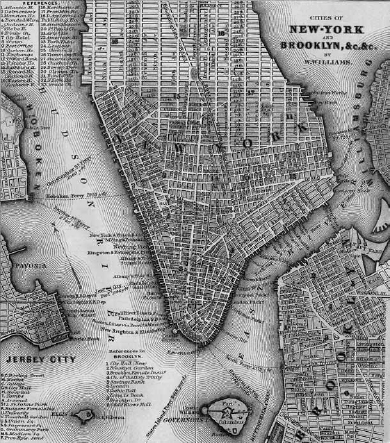

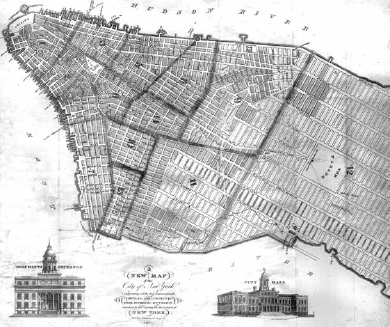

An 1847 map of lower Manhattan.

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2009 by Eric Ferrara

All rights reserved

Images are courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

First published 2009

e-book edition 2012

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.303.9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ferrara, Eric.

A guide to gangsters, murderers and weirdos of New York Citys Lower East Side / Eric Ferrara.

p. cm.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-677-0

1. Crime--New York (State)--New York--History. 2. Lower East Side--New York (N.Y.)--History. 3. Lower East Side--New York (N.Y.)--Guidebooks. 4. Criminals-New York (State)--New York. 5. Gangsters--New York (State)--New York. 6. Murderers--New York (State)--New York. I. Title.

HV6795.N5F47 2009

364.1097471--dc22

2009019604

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

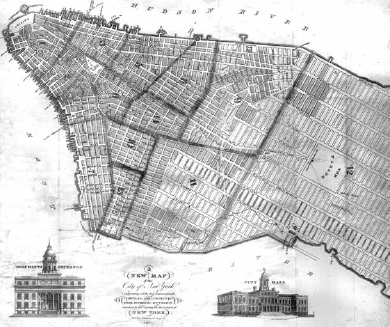

An 1827 map of lower Manhattan.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

A typical guidebook is filled with the names of men and women, justly famous or unjustly obscure, whose talent, energy or genius has bequeathed lasting contributions to the social good or the cultural trove. The sites of their great accomplishments and even their homes and humble birthplaces leave a legacy of pride, ennobling our historical memory.

Not this guidebook.

Murder, mob hits, riots, rumbles, bombings and even cannibalism are the events commemorated in the streets of the Lower East Side. Youll see the shift from the Irish political gangs to the Jewish union racketeers and the Italian extortionist rings and finally a return to political violence in the countercultural East Village; all along the way, youll experience the violence of the desperate marginal edge of social order. The story begins with the gangs.

The relationship of the nineteenth-century gangs to the citys politics reflects the broad history of post-Revolutionary New York and its emergence in the twentieth century, after one hundred years of struggle, as a progressive vanguard for the nation. Early nineteenth-century New York was a world in rapid transition toward industrialization, succumbing to the depressed wages and social instability that industrialization brings. Pre-Revolutionary New York had been a wealthy port, with a stable, if uneven, social fabric of lavishly aristocratic landowners surrounded by modest artisans and mechanics, the highly skilled laborers who, through the traditional artisanal guild systems, regulated prices and wages. It wasnt always smooth, but it was a kind of communal societyalbeit with an extravagant top endtacitly governed by a communal ethic, with a grousing recognition from the heights that no part of an integral society could be entirely neglected.

When industrialization arrived, it marched over New York with little regard for the citys quaint integrity. Industrialists quickly saw the advantage of unskilled labor over these high-cost craft masters supporting their live-in apprentices. Industry needed a limitless source of such labor to replace the artisan and drive wages down. That source was handily offered by the tens of thousands of impoverished and desperate immigrants flooding the New York port in search of a start at the very bottom. And thats exactly what those immigrants got, although the bottom had dropped much lower than anyone had ever thought possible.

This was the context of immigrant life: housing without running water or toilet facilities (the toilet was a ditch in the backyard), no sewage system, streets piled with garbage, pigs the immigrants couldnt afford to feed running wild in the streets alongside the thousands of abandoned children the immigrants also couldnt afford to feed and prostitutesprostitutes walking the streets, prostitutes waiting in the doorways, prostitutes reclining on the steps, prostitutes everywhere. It was estimated that one-third of the female population of New York in 1840 was or had been engaged in prostitution. And no surprise: a seamstress might earn between one and two dollars a week, working sixteen hours a day, seven days a week; a prostitute could earn nearly twice that in a day. Every second or third house in Five Points had an accommodation for prostitution of some kind. Nearly every building on Anthony Street between Centre and Orange housed a bordello.

If prostitution was nearly everywhere, alcohol was absolutely everywhere. Every building had an accommodation for whiskey. The saloon became a center of social life in the slum. The saloon owner, a man of the people, though a few steps above in income, became the local leadertrusted, respected and relied upon. He was equally connected to a powerful industry (liquor) and to a broad constituency (the neighborhood). He could hide a local gang member in trouble with the law; he could help him out with a small loan in a pinch. The slum invested its political strength in the saloon owner, and the list of saloon-owner power brokers in New York is a long one.

The old caucus method in New Yorks primaries was a gang rumble. Candidates appeared at the party hall with their gang of choice, fought and whoever was left standing after the brawl took the nomination, all possible objectors having fallen silent for the evening. Candidates employed gangs to scour the graveyards for the newly deadthey would be the voters in the next election. In one election in the Tenth Ward, there were no fewer than two thousand more voters than living inhabitants. Sly critics liked to say that Fernando Wood, the controversial Democratic mayor and champion of the working class and Irish, was elected by the unanimous vote of the dead. Repeat voting was another familiar scam. There was little risk of being caught as the polls themselves were guarded by the gangs. Wood, running for a second term, gave his police a furlough on election day, advising them not to visit the polls except to vote, and promptly drew out his Irish gangs to keep out Protestant Republican voters.

New York became a battleground between wealth and political poweron the one side the industrialist, intent on the immiseration of the immigrant to keep wages low, and on the other side, the political clout of the sheer numbers of immigrants cultivating their local favorites as candidates. Wealth had created its own worst enemy, a vast working class. The struggle played out at first in Tammany Hall graft and deadly riots but eventually gave us a successful labor movement and the New Deal.

Toward the end of the century, political clout shifted from within the residential wards to the Bowery itself, lined now with flophouses, burlesque concert halls, saloons, gambling parlors, beer halls, restaurants, poolrooms, theatres and sensational curiosity museums cheek by jowl with prosperous immigrant banks and insurance companies, radical labor union halls and early Marxist workingmens associations. In its bars, Tammany sachems rubbed elbows with their working-class support, while unions organized in Bowery halls for the eight-hour day. The gangs fought over turf.

Next page