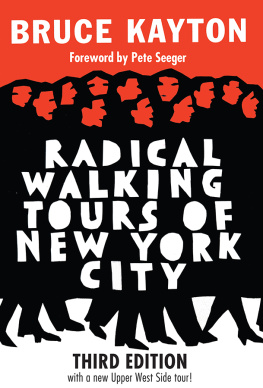

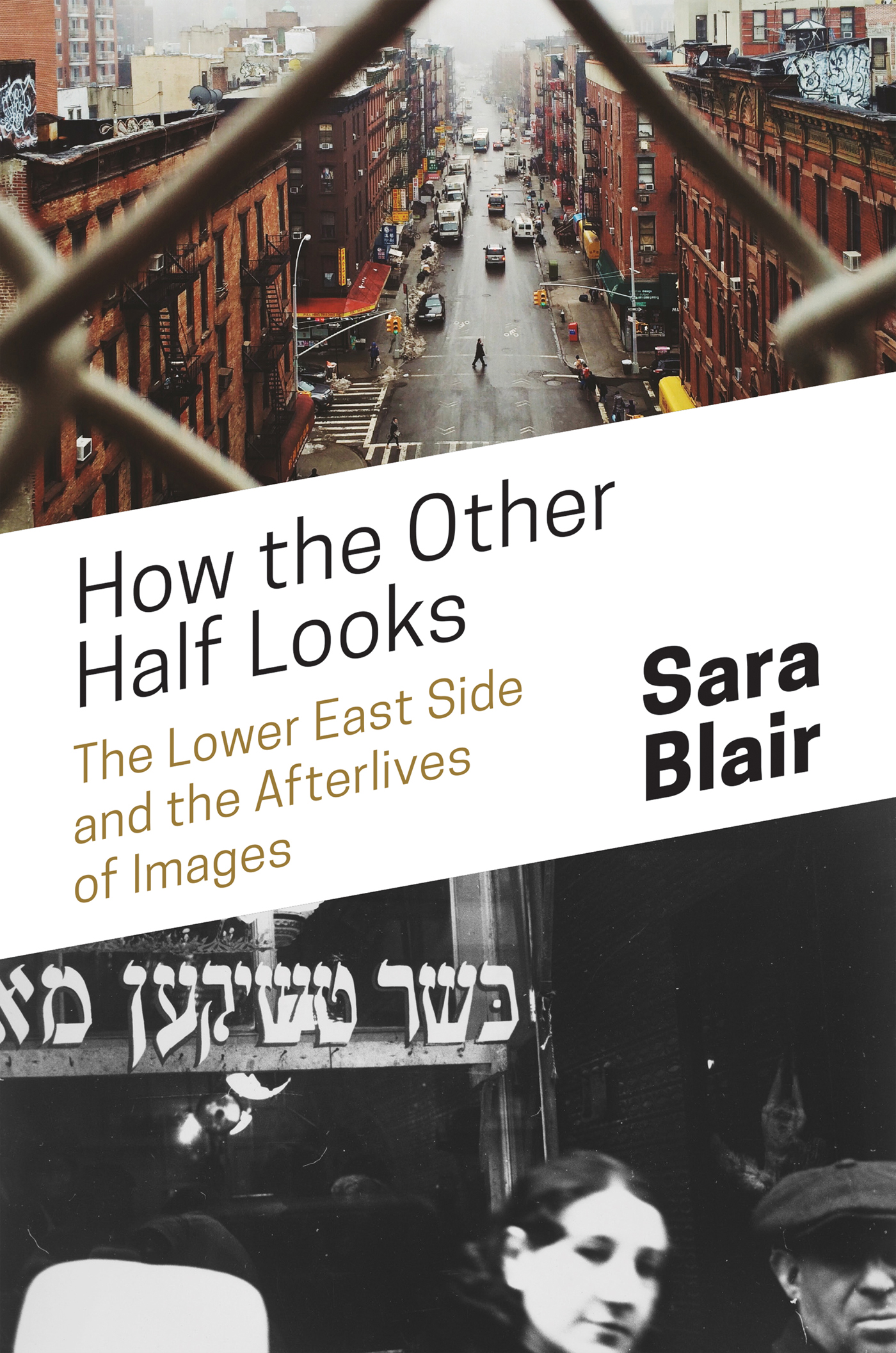

How the Other Half Looks

How the Other Half Looks

The Lower East Side and the Afterlives of Images

Sara Blair

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: (Top): Alexander Spatari, Chinatown seen through fence on a foggy day, NYC. (Bottom): Ben Shahn, detail from Untitled (Lower East Side, New York City), April 1936, Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum, gift of Bernarda Bryson Shahn, President and Fellows of Harvard College

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 9780-691172224

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017959640

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Text Pro and Cooper Hewitt

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Jonathan: always

for Ben and Miriam: a world repaired

Contents

List of Illustrations

Color Plates (following )

Figures

How the Other Half Looks

How the Other Half Looks

A Preview

When police-beat journalist Jacob Riis began using that quintessentially modern technology, the camera, to make the social life of New York Citys newest, most threatened (and threatening) subjects visible, he had no idea that his work belonged to a longer history of response to a key space of encounteror that it would come to inform a remarkable array of events unfolding over the century to follow. These included the evolution of photography as an art form, the rise of the American film industry, contests over literary realism, the dynamics of Jewish American cultural production, projects for rethinking the offices of poetry in Cold War America and those of the novel in the twenty-first century, and efforts to reanimate US print and visual media in global and digital contexts. Taking the project of observing the home of the other halfAmericas ur-ghettoas a point of departure, How the Other Half Looks conducts a critical experiment. It offers a site-specific account of visual experience, practice, and experimentation, and considers how these inform literary and everyday narratives of America, its citizens, and its modernity.

For such an experiment, the Lower East Side offers a remarkable opportunity. Throughout its long and evolving history, the ghetto and tenement district, variously conceived, figured, and named, remained inseparable from the urgently modern problem of managing social difference and change. Home to the first free black settlement in New York City and to successive waves of immigrants, working-class laborers, culture workers, and other others, the Lower East Side and its many avatars and analogues (the East Side, the Old East Side, Kleindeutschland, Baxter Street, Loisaida, Alphabet City, the Bowery; even, as I will argue below, the Five Points) has shaped the image repertoire of modern America. The neighborhoods long associations with labor, criminality, vice, racial heterogeneity, and the inassimilable have informed its representation in every genre and medium, and made it an enduring resource for experiments in observing and imagining America and its citizens, its histories and possible futures.

In part, the Lower East Side remained a staple subject in emerging US visual media, from illustrated journalism and the mass press to documentary photography and early cinema, because it subjected all comersits own residents, journalists and ethnographers, tourists and slummers, the guardians of health and welfare sent to police itto intensely heightened experience, especially in visual terms. On its crowded sidewalks, in its commercial thoroughfares and overcrowded tenements, whether seen from a safe ethnographic distance or at close range, it made the challenges and limits of American modernity (including the challenges of knowing such sites at all) strikingly visible. In the face of its unprecedented density and raw materiality, new technologies and practices for observing American social life were tested, from halftone reproduction and flash lighting to location shooting and techniques for the visualization of nuclear holocaust. These in turn generated representational and media histories, as well as habits of observation that focused literary and popular expression, projects of social reform and social control, and aspirations for the American modernity they shaped, celebrated, and resisted.

Focused on that unfolding history, How the Other Half Looks explores the complex life and afterlives of Americas downtown ghetto and tenement landscapes, as well as their inhabitants, as a source for an emergent iconography of modern experience, and a resource for probing the currency of new (and, for that matter, fading or outmoded) representational projects, genres, and media. Commentators have noted that the explosive growth of the Lower East Side as a site of entry into America and its ever-renewing newness coincided with an explosive growth in print culture, visual technologies, and mass publics, and with the rise of New York City as epicenter for their industry.old worlds and new, of lifeworlds emergent and radically transformativeshape its representation in visual and literary forms and in other media?

Two key notions require clarification from the outset: the question of mapping or location, and the matter of iconography (from the Greek , image, and , to write: image-writing).

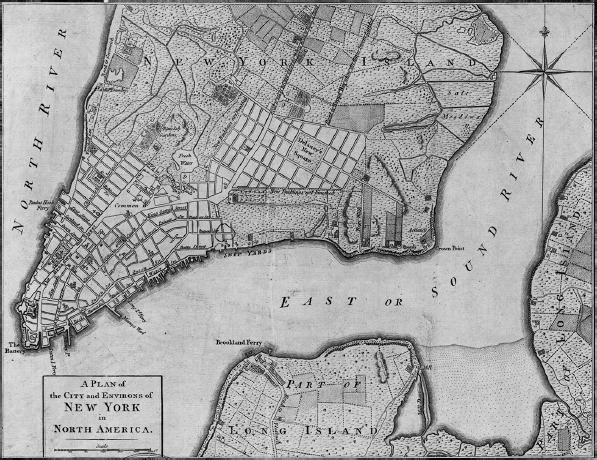

A onetime Lenape Indian habitation, Dutch colony, and English settlement by treaty (the booty of intercolonial warfare), the area served early in Manhattans Anglo-European life as a trading post and commercial enterprise zone, a source of farmland, and a nexus of maritime, mercantile, and military exchange. These prehistories marked the netherlands of the nineteenth-century city, lending them to a fluid imagination of poverty, progress, and ethnoracial type. The commercial logic of Dutch power, extended under the English (particularly that of the first English governor, Irish-born Thomas Dongan), had drawn a relatively varied Anglo-European population, including French Protestants and the soon notorious Irish.

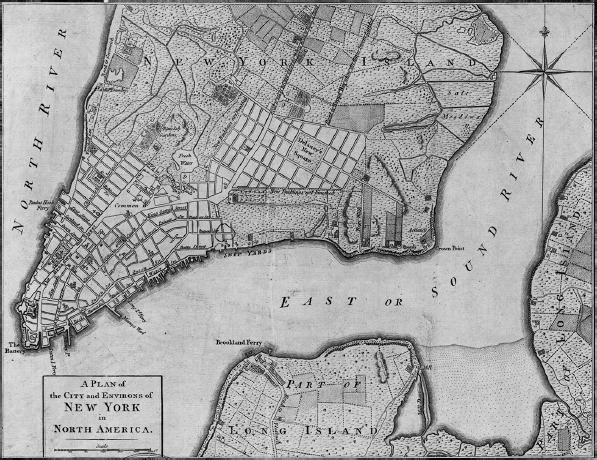

FIGURE P.1. A Plan of the City of New York (Corlears Hook as Crown Point during British Occupation), c. 1776. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Even a glance at that earlier vision, as recorded in an aspirational map made by British planners during colonial occupation, suggests how radically the actual city departed from it (

Vice, prostitution, disease; the rapid expansion of laboring classes and immigrant populations; transiency, crowding, and sharply rising density, all feeding genteel flight and the rise of the tenement: long before the so-called golden age of immigration or the rise of the Jewish ghetto, long before the Lower East Side came into view as such, its earlier avatars embodied, for everyday citizens, city-dwellers, and Americans at large, the downside of the citys rapid capital and industrial expansion, demographic growth, and nascent globalization. In so doing, it figured the perils of modernization as a social and cultural project. Throughout its various lives, in all its shifting spaces and boundaries, the territory that would become known as the Lower East Side brought home the threats and promise of American modernity.

Next page