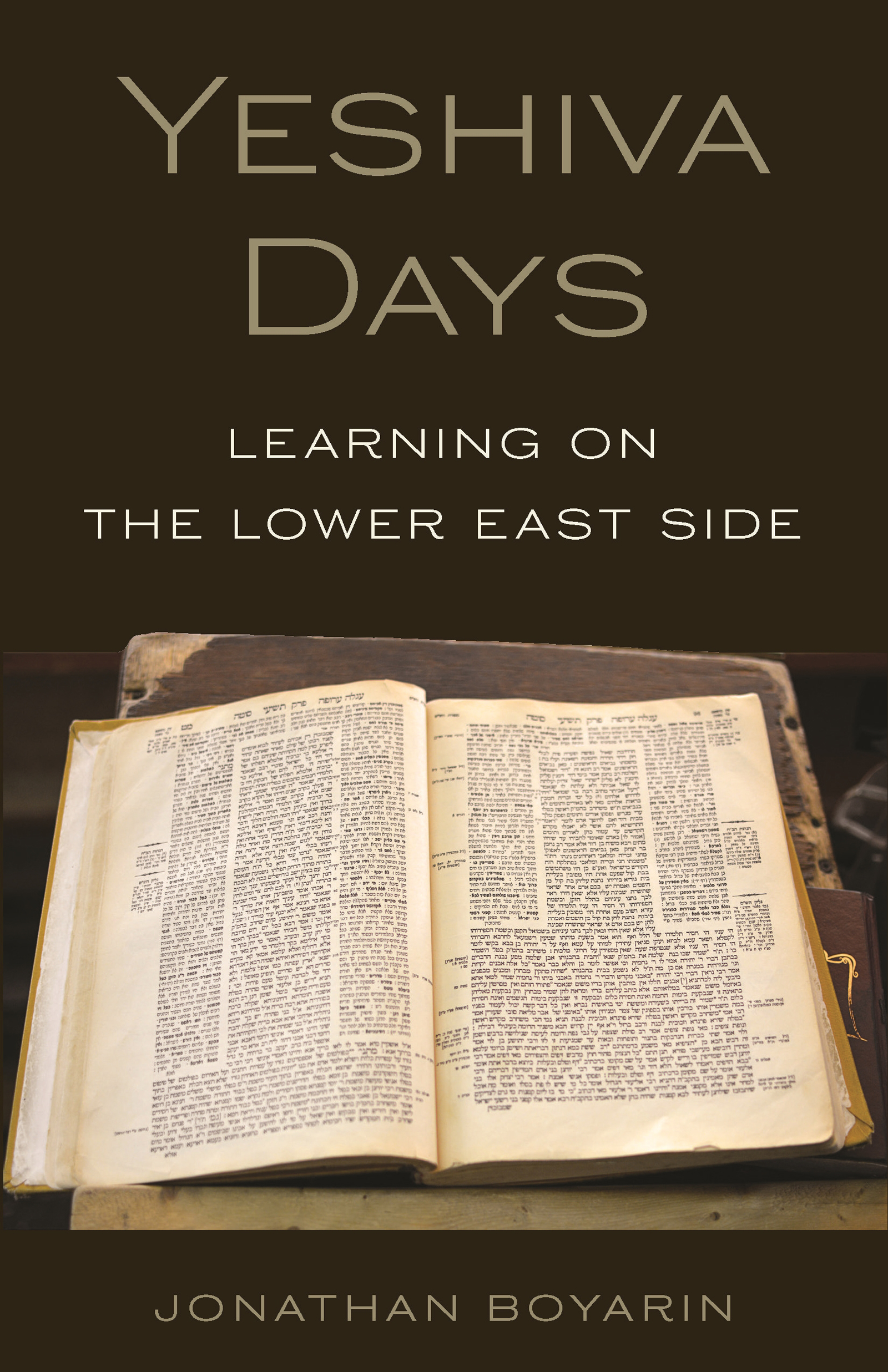

YESHIVA DAYS

Yeshiva Days

LEARNING ON THE LOWER EAST SIDE

JONATHAN BOYARIN

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Boyarin, Jonathan, author.

Title: Yeshiva days : learning on the Lower East Side / Jonathan Boyarin.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020014813 (print) | LCCN 2020014814 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691203997 (paperback) | ISBN 9780691203980 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780691207698 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Boyarin, Jonathan. | Jewish menNew York (State)New YorkBiography. | Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem (New York, N.Y.) | YeshivasNew York (State)New York. | Lower East Side, (New York, N.Y.)

Classification: LCC E184.37.B69 A3 2020 (print) | LCC E184.37.B69 (ebook) | DDC 974.7/1092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020014813

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020014814

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Fred Appel and Jenny Tan

Production Editorial: Leslie Grundfest

Jacket/Cover Design: Pamela Schnitter

Jacket/Cover Credit: Old copy of the Talmud in a classroom at the Lubavitch headquarters in Crown Heights, Brooklyn / Ira Berger / Alamy

To the memory of the Jews of Telz in Lithuania, members of the yeshiva and townspeople, martyred at the hands of the Nazis and their local collaborators.

In effect, every project of ethnography enters sites of fieldwork through a zone of collateral counterpart knowledge that it cannot ignore in finding its way to the preferred scenes of ordinary everyday life with which it is traditionally comfortable. The fundamental problem here is in confronting the politics of knowledge that any project of fieldwork involves and the ethnographers efforts to make this politics of knowledge itself part of the design of investigation.

DOUGLAS R. HOLMES & GEORGE E. MARCUS, PARA-ETHNOGRAPHY HTTP://KNOWLEDGE.SAGEPUB.COM/VIEW/RESEARCH/N307.XML

The secret things belong to the Lord our God; but the things that are revealed belong unto us and to our children forever, that we may do all the words of this law.

DEUTERONOMY 29:28

PREFACE

FOR CENTURIES, the central institution of traditional rabbinic learning among east European Jews and their descendants has been the yeshiva. The institution took its modern form in Lithuania and nearby portions of the Pale of Settlement over the course of the nineteenth century, as a place dedicated solely to study and attended by students, exclusively male, from distant places as well as the town or city in which the yeshiva happened to be located. Moreover, these yeshivas were generally independently funded, and not controlled by the local rabbis. Transplanted to the New World, yeshivas have remained central to the persistence and growth of Orthodox Jewish communities after the period of mass emigration and genocide. Today, the largest Lithuanian-style yeshiva in the United States is in Lakewood, New Jersey, while many others are located in New York City, upstate New York, and elsewhere in the United States.

As understood by traditional Judaism, Torah encompasses not only the Hebrew Scriptures, but also a vast sea of rabbinic texts stretching back two millennia and still being created in the present, as well as authoritative verbal discourses pronounced by teachers today. As the epigraph from Deuteronomy suggests, the work of understanding Torah is understood as a profound mix of human freedom, discipline, and responsibility. If Torah broadly is understood as the word of God, the authority of those rabbinic texts and discourses derives from a combination of the labor, talents, and fear of Heaven their authors devoted to understanding that divine word and to activating it as a human inheritance. Thus, whether the subject of study deals with overtly religious matters or with rabbinic law governing business relations, the study itself is understood not merely as another intriguing subject like math or science, but as probably the single most central form of divine service to which a Jew can devote himself.

The core text studied in the yeshiva is the Babylonian of Rabbi Joseph Karo. Students may spend time studying biblical texts as well, although with some exceptions, Bible study is not an organized or central focus of the yeshiva.

This book describes my experiences studying at Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem, or MTJ, a yeshiva near my home on New Yorks Lower East Side. I do not mean to present MTJ as a typical or representative yeshiva. Partly because it is small and neighborhood based, and partly because of the distinctive heritage and character of the Lower East Side Jewish community in which it is located, it is more informally structured than most Orthodox yeshivas. During the years described in this book, in addition to regular Talmud lessons taught Monday through Thursday, there were also a weekday morning class in the modern compendium known as the (homiletics), but not all those who studied regularly at MTJ participated in these structured lessons.

I had spent a good deal of time at MTJ in the 1980s, but hardly stepped back in until late 2011. At the beginning of that earlier stint, Reb Moshe Feinstein, the father of our current (decisor) of his generation, famous at once for his rigorous devotion to Orthodox law, his flexibility in the face of changed circumstances, his personal humility, and his availability to the entire community. The unusual mix of traditionalism and unpretentiousness that still characterizes MTJ represents his legacy.

That much I have known for decades, and indeed, some explanation of the quarter-century gap between my earlier and current studies at MTJ may be in order here. In 1983, I returned with my spouse, Elissa Sampson, from a year of fieldwork among elderly Polish Jewish immigrants in Paris. Those Polish Jews were resolutely secularist, and Elissa and I were struck by the vast cultural gap between them and their children, who for the most part seemed well integrated into French culture and little attuned to the Yiddish language and east European Jewish culture of their parents. This helped shape our view that, in order to persist, Jewish identity in diaspora requires some sort of everyday frame to tell us what it is that Jews do and dont do. That, along with a long-standing desire to gain more literacy in the traditional rabbinic texts, led me to join an adult mens beginners group at the yeshiva for a few years in the mid-1980s. Though I didnt initially conceive of my time there as fieldwork, it eventually led to some academic writing on the social character of reading.

I stopped attending that group around the time my first child was born, and had hardly stepped into MTJ in the intervening years, when the wonderful good fortune of a full years academic leave came my way in 2012the year I refer to in this book as my year. In the interim, and with much delay, I had finally commenced a full-time academic career. When my years leave began, I was teaching at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; a semester after it ended, at the close of the 20122013 academic year, I accepted a position at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Hence, I occasionally refer in this book to my various departures and returns between New York City and either Chapel Hill or Ithaca.