ADAK

ADAK

The Rescue of

Alfa Foxtrot 586

Andrew C. A. Jampoler

NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS

ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2003 by Andrew C. A. Jampoler

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

First Naval Institute Press paperback edition published 2011.

ISBN 978-1-61251-074-3

The Library of Congress has catalogued the hardcover edition as follows:

Jampoler, Andrew C. A., 1942

Adak: the rescue of Alfa Foxtrot 586 / Andrew C. A. Jampoler.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-59114-412-4 (alk. paper)

1. Aircraft accidentsAlaskaAleutian Islands Region. 2. Search and rescue operationsAlaskaAleutian Islands Region. 3. Aeronautics, MilitaryAccidentsAlaskaAleutian Islands Region. 4. Aircraft accidentsInvestigationUnited States. 5. Survival after airplane accidents, shipwrecks, etc.

I. Title.

TL553.525.A4J35 2003

363.12481097983dc21

2002013560

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 119 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

Cover image courtesy of Robert Bausch, www.bauschdesign.com

Illustrations courtesy of Rob Ebersol

Contents

This is the flight crews story.

It is dedicated to them,

to those who survived and

to the memory of those

who did not.

The Findings of Fact in each chapter are quoted from the Judge Advocate General (JAG) investigation conducted by thenLt. Cdr. James A. Dvorak, U.S. Navy, of Patrol Squadron 9, in November and December 1978 immediately after the ditching. His cooperation is gratefully acknowledged, as is the generous assistance of Ed Caylor, Ed Flow, Bruce Forshay, Matt Gibbons, Howard Moore, Garland Shepard, and John Wagner, whose story this is.

Other welcome help came from interviews of or correspondence with Aleksandr Arbuzov (former master of the Mys Sinyavin), Bruce Barth, Cynthia Beck, Chris Behrens, Geoff Birchard, John Branchflower (DF 704), L. Anthony Bracken (naval attach, Moscow), Jim Burk, Jim Carman, Cliff Carter (Scone 92), Mary Casto, Pat Conway (XF 675), Pete Cressy (Patrol Squadron 9), Dave DeVarney, Mitchell Dukovitch, Allen Efraimson, Alan Feldkamp (Scone 92), Jon Feller, Rory Fisher (Patrol Squadron 9), Carol Flow, Randall Flynn, Nevins Frankel, John Frost, Robert Hay Jr., Jerry Holland, Lorren Jackson, Rick Kirkland, Dick Klass, Phillip Kolczynski, Kathleen Kujawa, Rachel Lewis, Perry Martini (aide and flag lieutenant, commander, Patrol Wings Pacific Fleet), Ralph McClintock (USS Pueblo), Mark Mergard, Denny Mette (XF 675) and Cindy Mette, Skip Miner, Larry Mitchell (24th SRS), Bob Myer (JB 022), Rod OConnor (USCGC Ironwood), Joanne Petrie, Bill Porter (CG 1500), Bud Powers (Patrol Squadron 9), John Powers (CG 1600), Ron Price (XF 675), Al Ross, Chris Schroeder, John Shackleton (public affairs, NAS Moffett Field), Vladimir Shevlyakov, Philip Silvestri, Brenda Hemmer Smith, Sharon Snyder, Louis Tavares, Tony Tuliano (USCGC Jarvis), Dave Vonderheide, Shelly Wagner, Scott Wilson, and John Yackus. Any errors are, of course, my responsibility.

My thanks also to Al and Jo Hart, my agents, for their encouragement, assistance, and counsel, and especially to Suzy, my wife of thirty-seven years, who worked while I imagined myself an author.

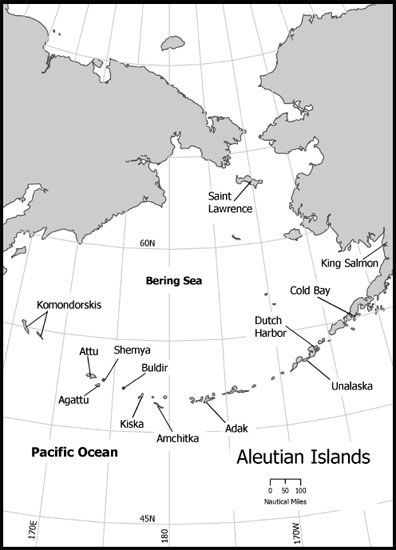

A line of bright, red triangles, dramatically annotated Ring of Fire, lies immediately above the Aleutian Islands in one of the National Geographic Societys maps of the Pacific Ocean. The symbols announce that the earth is restless along this seam where the North American and Pacific tectonic plates meet, a work in progress. The eternal, grinding collision of these plates ensures that the Aleutians experience frequent earthquakes, hundreds in an average month. Most are barely detectable, but several temblors in the last century were rated on the Richter scale as 8 and above, each as powerful as the 1906 quake that devastated San Francisco.

Even the earths magnetic field seems to be still under construction here. Aeronautical charts of the area are sprinkled with cautions about large magnetic disturbances over short distances, making conventional wet compasses unreliable guides to direction. The caution for Kagalaska in the central Aleutians, one mile east of Adak Island across a narrow strait, is typical of these warnings. Magnetic disturbance of as much as 11 exists at ground level near the northwest end of Kagalaska Island, it announces in bold magenta type.

Extremes of topography and weather assemble naturally in this region, too. The eponymous Aleutian Trench lies just south of the islands. At its deepest point, the waters of the trench go down 4,200 fathoms, almost 4.8 miles, putting it among the great submarine canyons of the world. The shallow Bering Sea, north of the archipelago, with its notorious rogue waves and dense ice fogs as opaque as milk, has been a famous killing ground for fishing ships for three centuries.

The Aleutian Islands and the Bering Sea

Two circular ocean currents bracket the islands north and south, slowly churning unimaginable quantities of cold salt water past the Aleutians in counterclockwise loops, or gyres. On an oceanic scale, these gyres on both sides of the Aleutian chain are relatively small; nevertheless, they influence the rich marine life of the region and help shape its dramatic weather.

The Aleutians appear to have been first settled by native peoples moving to the islands from east to west, backfilled about eight thousand years ago, perhaps three millennia after the Bering land bridge that once connected Asia to North America was submerged beneath rising waters. (Land bridge erroneously suggests a fragile connection. In reality, the bridge was one thousand miles across.) The retrograde pattern of settlement suggests that the inhospitable, treeless islandsthe peaks of submarine volcanoes once the ice cap withdrew and the ocean rosewere no ones first choice as a domicile, judged inferior even to the bleak Arctic Ocean shore that still sustains the Eskimo of mainland Alaska and the Inuit of Canada.

The second Kamchatka Expedition of Discovery, led by Vitus Bering, a Danish-born, Russian navy officer, opened the Aleutians after 1740 to Russian hunters and trappers. It also brought catastrophe to the islands native peoples, whom the Russians named Aleuts.

There were not many Aleuts (they called themselves Unangan) when the Russians came, perhaps never more than twenty-five thousand, wresting a difficult life in small dug-out hovels, hunting the mammals of the sea and fishing its waters from high-prowed baidarkas, rugged oceangoing canoes. Mean conditions on the islands for their human residents were offset by the Aleutians generosity to their other fauna. The region once teemed with seals and sea otters, but these animals unwittingly committed the error of being worth more dead than alive. The sea otters beautiful coats (the sleek beasts had no layer of fat to keep them warm and relied entirely on their thick fur for insulation in cold water) made them especially precious.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).