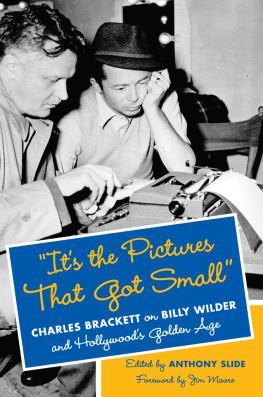

Some Like It Wilder

SCREEN CLASSICS

Screen Classics is a series of critical biographies, film histories, and analytical studies focusing on neglected filmmakers and important screen artists and subjects, from the era of silent cinema to the golden age of Hollywood to the international generation of today. Books in the Screen Classics series are intended for scholars and general readers alike. The contributing authors are established figures in their respective fields. This series also serves the purpose of advancing scholarship on film personalities and themes with ties to Kentucky.

Series Editor

Patrick McGilligan

SOME LIKE IT

WILDER

The Life

and

Controversial Films

of

Billy Wilder

GENE D. PHILLIPS

Copyright 2010 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Phillips, Gene D.

Some like it Wilder : the life and controversial films of Billy Wilder /

Gene D. Phillips.

p. cm. (Screen classics)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-2570-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Wilder, Billy, 1906-2002. 2. Motion picture producers and directors

United StatesBiography. I. Title.

PN1998.3.W56P45 2010

791.430233092dc22

[B] 2009045857

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

For Fred Zinnemann

Another exile in Hollywood

When you think about the breadth and scope of what Billy Wilder has written, produced, and directed, and then take into consideration that English is not even his first language, then you see that his entire output is staggering.

Stanley Donen, film director

Contents

Foreword

Fred Zinnemann Speaking

After I finished film school, I got work as a cameraman in Berlin. I was fortunate to be the assistant to Eugene Schfftan, one of the best German cameramen during the golden age of German cinema in the 1920s. One of the films that Schfftan photographed was Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday), a semidocumentary made in 1929 about four young people spending a weekend in the country. The film was written by Billy Wilder and directed by Robert Siodmak.

I only carried the camera around and measured the focus, but I was pleased to be working with talented people like Billy Wilder and Robert Siodmak. The picture was made on a shoestring, and we had to stop every two or three days to raise more money. It was a smash hit, and Billy, Robert, and I all eventually migrated to Hollywood and became directors there.

My career in Hollywood in some ways ran parallel to Billys. For example, each of us made a picture in the ruins of Berlin after World War II, in 1948. I directed The Search, about displaced European children, and Billy directed A Foreign Affair, about the Allied occupation of Berlin. Both pictures were successful at the box office.

The cold war years, a period of uncertainty in the aftermath of World War II, spawned Senator Joseph McCarthys witch hunt for Communists, and the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings. In 1950 Cecil B. De Mille, who was very right wing, persuaded the board of the Screen Directors Guild (SDG) to require a loyalty oath of the membership. Joseph Mankiewicz, the president of the SDG, opposed De Milles resolution. Billy Wilder and I, among others, signed a petition supporting Mankiewicz.

The De Mille faction sent out messengers on motorcycles late at night with a letter to each of us who supported Mankiewiczs stand. There werent any direct threats in the letter, but there were heavy hints that our careers were on the line if we didnt endorse De Milles resolution.

At the general meeting of the SDG membership, the crunch came when De Mille read our petition to reject his demand for a loyalty oath. De Mille said it was signed by Mr. Vilder and Mr. Zinnemannnnn, indicating that we were foreigners and that our petition was un-American. With that, the membership booed De Mille. John Ford got up and said, Cecil, youre a good picture maker, but I dont like what you stand for. Then Ford moved that De Milles motion for a compulsory loyalty oath be rejected, and it was.

Billy and I seemed to have kept pace with each other throughout our careers. We both won Academy Awards for directing featurestwo apiece. Billy won for The Lost Weekend and for The Apartment; I won for From Here to Eternity and A Man for All Seasons.

Although Billy and I began our careers in Germany, we have always thought of ourselves as Hollywood directorsnot just because we worked in the American film industry for so many years but because we both believed in making films that would entertain a mass audience. Neither of us wanted to make pictures that were aimed at an eliteintellectual or otherwise. We always believed that motion pictures were a popular art, meant to entertain the public at large. And that is the kind of movie that we made.

Acknowledgments

To begin with, I am most grateful to Billy Wilder for granting me an extended interview in his Hollywood office, which was the starting point of this book. In addition, I wish to single out the following among those who have given me their assistance in the course of the long period in which I was engaged in remote preparation for this study. I conducted interviews with filmmaker Fred Zinnemann about how he and Wilder started their careers together in Berlin; with Otto Preminger about acting in Wilders Stalag 17; with Howard Hawks, for whom Wilder cowrote Ball of Fire; and with Wilders friends and fellow directors William Wyler, George Cukor, John Huston, and Garson Kanin.

I met with actors Olivia de Havilland (Hold Back the Dawn), Fred MacMurray (Double Indemnity and The Apartment), Pat OBrien (Some Like It Hot), and Christopher Lee (The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes) about working with Wilder; with playwright-screenwriter Samuel Taylor in New York about collaborating with Wilder on Sabrina; with screenwriter Ernest Lehman at the Cannes Film Festival about working with Wilder on Sabrina; with film executive Edward Small in Hollywood about executive producing Witness for the Prosecution; and with Ted Schmidt about serving as an assistant editor on

Next page