CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

O n 13 November 1942 War Bulletin No 901 informed an astonished Italian people that one of the Regia Aeronauticas (Italian Air Forces) most famous heroes, Maggiore Carlo Emanuele Buscaglia, a torpedo-bomber ace, was missing in action following an attack on Bougie Harbour in Algeria. This Osprey Combat Aircraft volume spotlights Buscaglia and his fellow airmen who flew the Regia Aeronauticas torpedo-bombers, which were among the most lethal weapons fielded by Italy during the Mediterranean war.

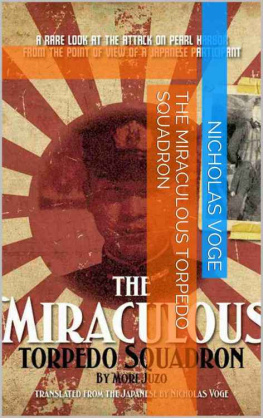

The Italians, notably lawyer Raoul Pateras-Pescara and Captain of Naval Engineering Alessandro Guidoni, had conducted tests of aerial torpedoes from 1914. Some aerial torpedo attacks had been attempted as early as World War 1, but to no avail. Trials continued through the 1920s and 1930s using several aircraft types, until in 1938 the first aerial torpedo produced by the Whitehead firm of Fiume was paired with the SIAI Marchetti (also known as Savoia-Marchetti) S.79, later named Sparviero (Sparrowhawk). Thanks to its remarkable speed and manoeuvrability, the S.79 was destined to become the Italian aircraft of choice for the torpedo-bomber role.

Yet, owing to rivalries between the Italian Navy and Air Force, which disputed each others control and financing of the new role, Italy entered the war in 1940 lacking trained crews, specialised units and sufficient air-launched torpedoes to wage an adequate anti-shipping war. This situation was aggravated by the poor performance of the Italian level bombers, whose weapons, dropped from too high an altitude, dispersed and mostly failed to hit enemy ships. Those aboard the targeted vessels were usually able to spot and avoid the falling bombs, although the ships were often straddled and, in many cases, suffered damage from near misses.

Luckily, Generale di Squadra Aerea Francesco Pricolo, the Regia Aeronauticas Chief of Staff since November 1939, intervened to resolve this absurd situation. Pricolo was a strong supporter of the potential new torpedo-bomber branch, and shortly after his appointment he had hastily ordered a batch of 30 aerial torpedoes from Whitehead. To further accelerate this process following Italys entry into the war, Pricolo ordered a further batch of 50 aerial torpedoes (formerly allocated to Germany) for the air forces new role in July 1940. Thanks to his initiative, Italy at least had a modest quantity of torpedoes at its disposal during the first months of war. Otherwise, there would have been nothing.

In the torpedo-bomber role the S.79 proved to be an insuperable and outstanding aircraft. Thanks to the heroism of their crews, the Sparvieri sank and damaged a number of Allied ships and became a constant threat to Allied naval convoys in the Mediterranean. The successes they achieved, in spite of suffering heavy losses, earned the torpedo-armed S.79 the nickname Gobbi Maledetti (damned hunchbacks) due to the distinctive dorsal hump of the aircrafts cockpit roof. The S.79 was permanently associated with the most skilled torpedo aces, celebrated in wartime Italy as true heroes just as fighter aces were in other belligerent countries.

With these airmen aboard, the deeds of the Sparvieri became almost legendary, making the aircraft as famous to the Italians as Mustangs, Spitfires and Messerschmitts were to the Americans, British and Germans, respectively. Due to their achievements, which made them the Regia Aeronauticas most lethal wartime weapon, the S.79s were considered extremely successful. Indeed, they were worthy of being counted among the most effective land-based torpedo-bombers of the whole conflict.

1940 THE BEGINNING

A s already related, following the disappointing performance of Italian high-level bombers in the anti-shipping war, Generale Pricolo urgently ordered that the first Italian torpedo-bomber unit be rushed into action. Thus on 25 July 1940 at Gorizia-Merna airfield, the so-called Reparto Sperimentale Aerosiluranti (Experimental Torpedo-bomber Unit, later renamed Speciale) was officially formed.

Maggiore Vincenzo Dequal replaced Capitano Amedeo Mojoli as CO of theReparto Sperimentale Aerosilurantiin the summer of 1940 (Aeronautica Militare)

The first CO of the new unit was Capitano Amedeo Mojoli, who, some days later, handed over command to Maggiore Vincenzo Dequal. Five handpicked pilots and crews had been assigned to the unit. The pilots were Maggiore Enrico Fusco, Tenenti Carlo Emanuele Buscaglia, Franco Melley and Carlo Copello and Sottotenente Guido Robone. Naval officers Tenente di Vascello Giovanni Marazio and Sottotenente di Vascello Giovanni Bertoli were also assigned to the unit as underwater weapons specialists.

Between 23 July and 5 August the unit took on charge seven S.79s fitted with torpedo crutches. After undertaking a hasty training period, the Aerosiluranti were ready to make their operational debut. The Regia Aeronautica thus acquired a new type of unit, whose S.79s left Gorizia on 10 August 1940 for North Africa. The next day the aircraft stopped over at Rome-Ciampino airport so that the pilots could meet Generale Pricolo in the Italian capital. With the formalities over, the unit set off for Libya, the S.79s reaching Tobruk T5 airfield on the 12th and subsequently moving to El Adem airfield, which was deemed to be more suitable for torpedo-bomber operations.

The first targets for the Aerosilurantis combat debut were Royal Navy warships anchored in Alexandria harbour. On 15 August 1940 the five Reparto Speciale Aerosiluranti S.79s, flown by Maggiori Dequal and Fusco, Tenenti Buscaglia, Copello and Melley and Sottotenente Robone and their crews, took off from El Adem at 1928 hrs. Each aircraft carried one 450 mm Whitehead torpedo slung in the port ventral position. These weapons were 5.46 m (17.9 ft) long, weighed about 876 kg (1930 lb) and had an explosive charge of 170 kg (374.5 lb). The feasibility of carrying two torpedoes had been tested, but this seriously impaired the S.79s performance. Hampered by mist and low clouds, the aircraft reached their objective between 2130 hrs and 2145 hrs. Splitting into two formations, they were welcomed by fierce anti-aircraft fire.

Three S.79s were forced to abandon the mission because of poor visibility over the target and dangerous fuel shortages. The action was vividly described by 1 Aviere Marconista Giuseppe Dondi, a wireless operator aboard Tenente Copellos aircraft;

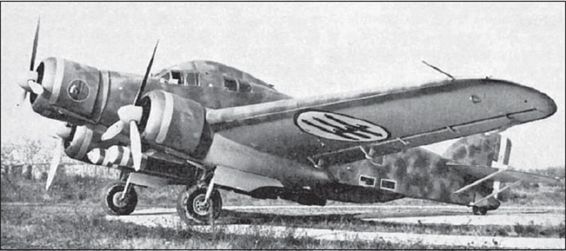

An S.79 loaded with two torpedoes. This option was trialled but rejected when it was realised that such a heavy load badly affected the S.79s performance. From then on the only time aircraft were seen with two torpedoes underslung was during transport flights

Six hundred, five hundred, four hundred metres and these damned clouds are even lower here is the trick! At last we emerge at less than 100 metres, and straight as a spindle we find ourselves over a deserted enemy beach. One tight turn to the left brings us over open sea again. Alexandria cannot be far. These damned clouds want to trick us. We head in again, and as if by magic one, two, ten, thirty searchlights switch on, their beams combing the sky, crossing one another, pursuing us, lifting and lowering in a possessed dance.