CHAPTER ONE

WAR AND PEACE

I n October 1920, a quietly spoken 23-year-old former soldier and ship designer by the name of Ernst Zindel joined a small aviation research bureau set up by the respected aircraft designer Professor Hugo Junkers in the Saxony-Anhalt town of Dessau, lying at the junctions of the Mulde and Elbe rivers. Junkers, whose entrepreneurial and academic talents had earned him an impressive reputation within the German aircraft and engineering industries, and Zindel, a Bavarian who had been badly wounded while serving with an infantry regiment in World War 1, would go on to enjoy a close and profitable relationship until Junkers death in 1935.

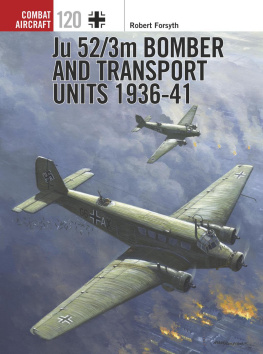

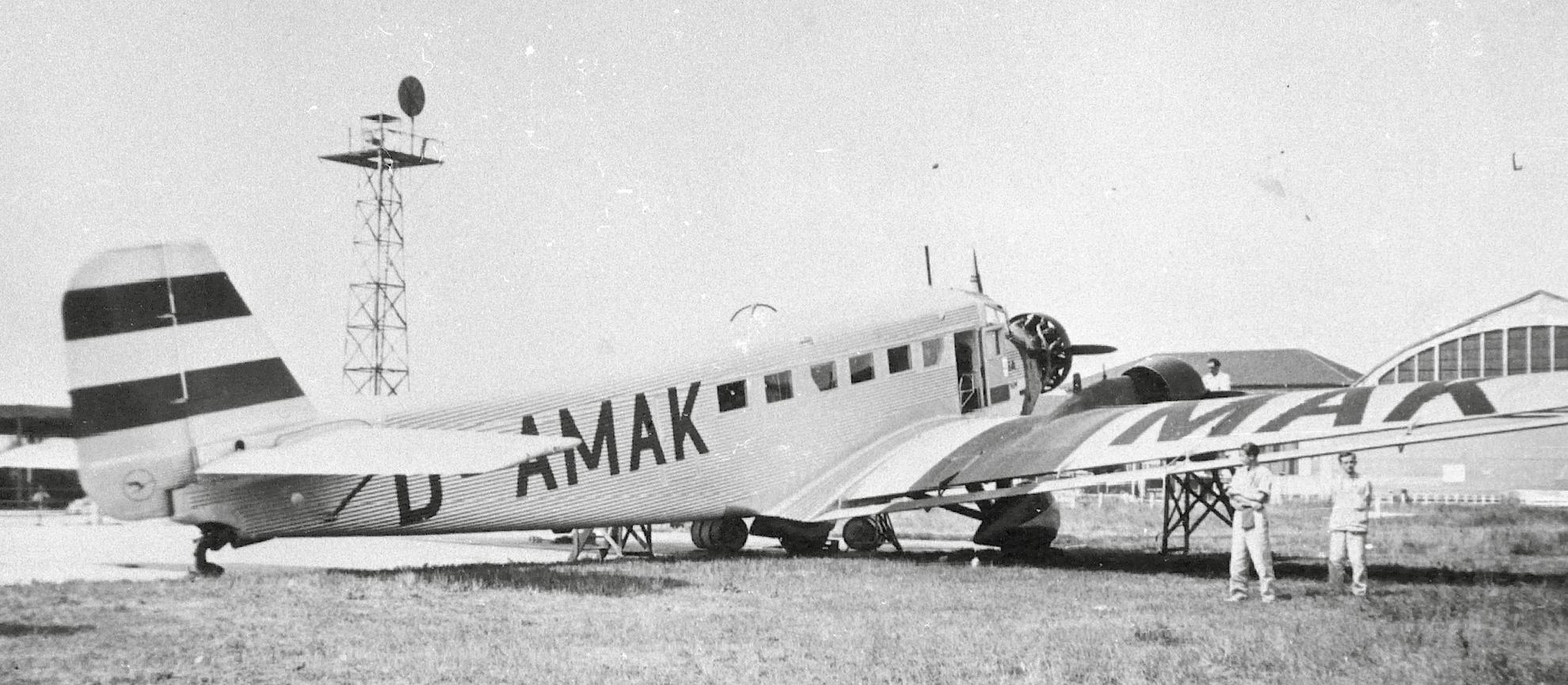

Lufthansas Ju 52/3m Wk-Nr 5294 D-AMAK VOLKMAR VON ARMIN parked off the apron at Taliedo aerodrome in Milan. The aircraft bears the national tail markings used prior to the Nazis taking power in Germany

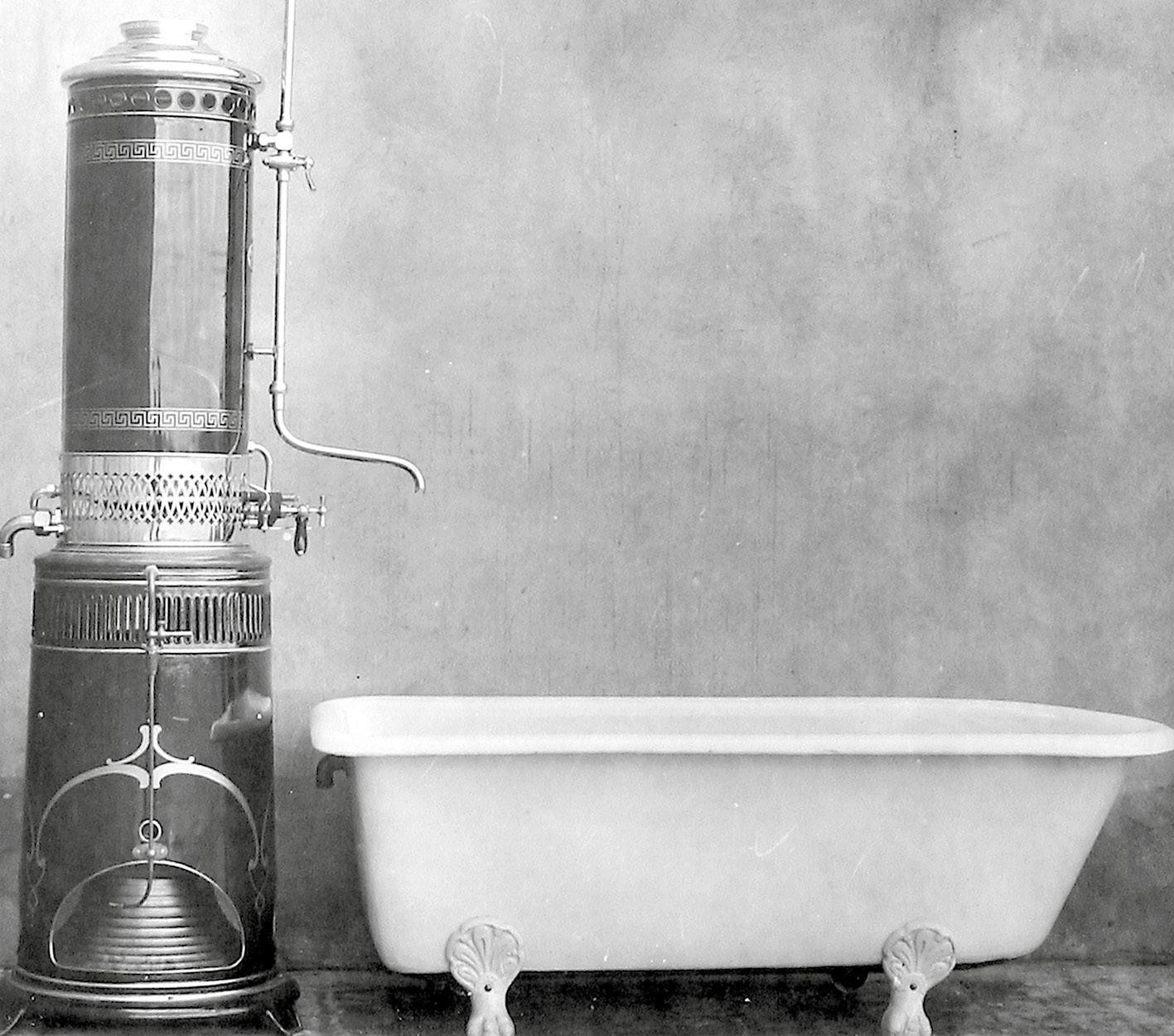

Zindel had been attracted by Junkers insightful and progressive use of metal in the aircraft which he had designed and which had been manufactured by his Junkers Flugzeugwerk company, but he had joined the firm at a difficult time. Despite Junkers burgeoning manufacturing interests, which included the production of water heaters, metal buildings and furniture, the post-war economic environment and the drastic restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles in Germany cast a dark shadow over the company, forcing him to cut back his workforce from around 2000 employees to just 200. No longer permitted to build aeroplanes or at least operating with severe curtailment Junkers Flugzeugwerk placed its emphasis on the production of water heaters, calorimeters, metal furniture, cutlery and household appliances.

Initially, metalwork for all Junkers products had been undertaken by hand using the traditional skills of tinsmiths and blacksmiths, but in the case of the aeroplane construction that remained, the firm had introduced Duralumin. It was not all plain sailing. Considerable investigative work had been needed to overcome the unavoidable problems of corrosion and fatigue, as well to devise improvements in joining, welding and riveting. Of particular concern was the problem of corrosion inside tubing and frameworks.

Ernst Zindel (left) joined the Junkers firm in 1920 and quickly became one of Hugo Junkers key men. From 1927 he was officially the companys chief design engineer, though to all intents and purposes he had filled that role since 1923. A modest and incredibly knowlegeable man, he was involved in the design and development of many of Junkers aircraft, but arguably the Ju 52/3m was his greatest legacy. He remained with Junkers through to 1945. He is seen here with a model of Ju 52/3mg2e Wk-Nr 5093, coded D-ALUG and named JOSEF ZAURITZ by Deutsche Luft Hansa. By spring 1940 this aircraft was serving with KGr.z.b.V.106. On the table in front of Zindel are scale drawings of the Ju 52/3m

Eventually, however, after persevering with sheet metal, it was recognised that corrugated Duralumin was a very suitable material. Although the parasitic drag associated with corrugated Duralumin was more of a problem than with smooth skins, it was not too much of an issue when considering the relatively low aircraft speeds of the time. Joining corrugated metal panels or joining them to smooth panels, however, were difficult processes requiring considerable skill. Nevertheless, during the post-war years, Junkers did introduce a number of greatly valued machines and machine processes that were subsequently widely adopted in aeronautical metal engineering, such as stretching, swaging (forged reduction), upsetting (forged increasing), turning, stamping and pressing.

Finally, the ban on the manufacture of commercial aircraft in Germany was lifted in 1922 as a result of definition of use and Junkers resumed work in construction, the testing of materials and wind tunnel testing. However, an ill-fated venture with the Russian government during the early 1920s had almost resulted in financial disaster. Germany had been eager to cooperate in any bi-lateral ventures with Russia to allow continued if not covert development of its aircraft industry. By signing the Treaty of Rapello, Russia had declared herself willing to place airfields, aircraft manufacturing facilities and labour at Germanys disposal in return for German technical knowledge and training. The potential for the mass manufacture of aircraft in Russia, free of Allied intervention was irresistible.

In November 1922, encouraged by the German government to the tune of 100 million Reichsmarks, Junkers signed a contract with the Russian government to build airframes and engines designed by his company for use by the Soviet Air Force at a factory near Moscow. Professor Junkers was well aware that a lucrative market still existed for military aircraft as well as civil, and that wherever possible every commercial type should be built with potential military conversion in mind.

Meanwhile, Junkers went at full pelt to build a series of all-metal aircraft, including the single-engined F 13, the worlds first metal airliner, the origins of which went back to 1919. Such was the ensuing success and reliability of the F 13 that, by the late 1920s, examples were in service in more than 30 countries including the USA, Bolivia, Colombia, Austria, Great Britain, Italy, Persia, Poland, Russia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Sweden and Switzerland.

In 1923 work was completed on the A 20, a mass-produced, purpose-built, low-wing mail and aerial mapping monoplane, again made of Duralumin and powered by either a 160 hp Mercedes D IIIa engine in the case of those aircraft manufactured by Junkers, or by a 220 hp Junkers L 2 in the case of aircraft built by the Swedish-based Junkers subsidiary, AB Flygindustri. The A 20 was operated by the Junkers-Luftverkehr airline on its overnight mail service between Warnemnde and Karlshamm, in Sweden, while a new German airline, Luft Hansa, used at least ten aircraft for the carriage of night mail, newspapers and general freight. Other users included Swiss, Chinese and Chilean carriers and the Turkish military air arm. A small quantity was also built in Russia for the Soviet Air Force.

As a result of restrictions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, Hugo Junkers was forced to suspend work on the manufacture of metal aircraft during the 1920s and instead placed emphasis on the production of domestic appliances such as water heaters (an example of which is seen here), metal furniture and cutlery

Between 1924 and 1928, Junkers produced several successful, if short-lived, commercial designs, including the J 23 (G 23), the firms first three-engined machine. The J 23 would be the forerunner of many successive multi-engined, all-metal, cantilever transport aircraft and was essentially an enlarged F 13, the production of which was prompted as a result of demand from the steadily burgeoning German air transport market. While an outstanding aeroplane for its size, the F 13 could carry only four to five passengers and limited freight, whereas the new design called for accommodation for up to nine passengers. At first the J 23 suffered from limitations in power imposed by the Versailles restrictions, which stipulated that only two 100 hp Mercedes and one Junkers L 2 engine could be fitted. The latter was a four-stroke, six-cylinder, in-line petrol engine built by the Junkers engine business, Junkers Motorenbau.