Also by Lisa Appignanesi

Mad, Bad and Sad: A History of Women and the

Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present

All About Love: Anatomy of an Unruly Emotion

Losing the Dead

Freuds Women (with John Forrester)

Simone de Beauvoir

The Cabaret

Femininity and the Creative Imagination:

Proust, James and Musil

FICTION

Paris Requiem

The Memory Man

Kicking Fifty

Sacred Ends

Sanctuary

The Dead of Winter

The Things We Do for Love

A Good Woman

Dreams of Innocence

Memory and Desire

EDITED VOLUMES

Fifty Shades of Feminism (with Rachel Holmes and Susie Orbach)

Free Expression is No Offence

The Rushdie File (with Sarah Maitland)

Dismantling Truth (with Hilary Lawson)

Science and Beyond (with Stephen Rose)

Ideas from France: The Legacy of

French Theory

Postmodernism

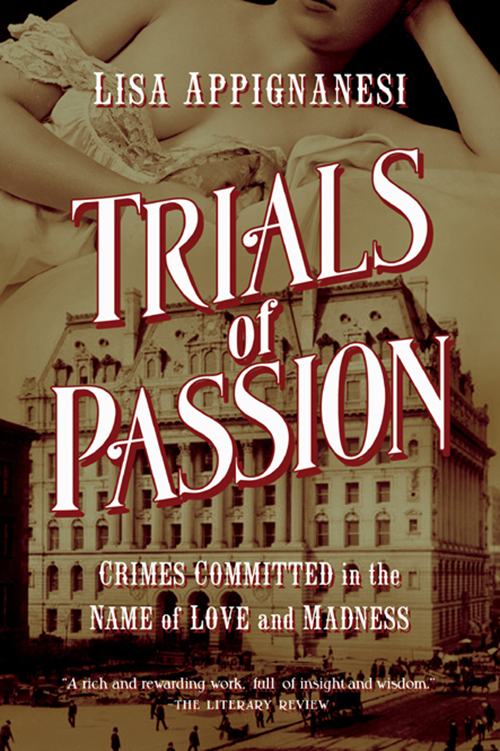

TRIALS OF PASSION

Pegasus Books LLC

80 Broad Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10004

Copyright 2014 by Lisa Appignanesi

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition July 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without

written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in

connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part

of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any

means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without

written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-60598-814-6

ISBN: 978-1-60598-815-3 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

For

Suzette Macedo

Adam Phillips

Marina Warner

(friends who always inspire)

Every love story is a potential grief story.

Julian Barnes

I must draw an analogy between the criminal and the hysteric. In both we are concerned with a secret, with something hidden ... In the case of the criminal it is a secret which he knows and hides from you, whereas in the case of the hysteric it is a secret which he himself does not know either, which is hidden even from himself... The task of the therapist, however, is the same as that of the examining magistrate.

Sigmund Freud

This book would not have been possible without the individual scholars who have come before me in the many fields this volume dips into: Joel Eigen, Gerald N. Grob, Ruth Harris, Allen Norrie, Roger Smith, Nikolas Rose, Tony Ward, Martin J. Wiener, to name but a few. For the case material and help provided, I thank the National Archives at Kew; Mark Stevens of the Berkshire Record Office which hosts the Broadmoor Archives and whose Broadmoor Revealed appeared while I was working on the latter parts of this book; the archivists who guided me through the dossiers of the Prefecture de Paris now held at the Archives de Paris; and the invaluable Kate Elms at the Brighton and Hove Archive. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the many psychiatrists, psychoanalysts and lawyers who have answered my questions along the way, amongst them Estela V. Welldon, Cleo Van Velsen, Frank Farnham, Michael Kopelman, Lisa Conlan, Faisil Sethi, Helena Kennedy and Martha Spurrier.

I am grateful to my editor, Lennie Goodings, and my agent, Clare Alexander, two formidable women, who between them steered me in the direction that eventually became this book. My thanks also to Victoria Pepe, to Zoe Gullen at Virago, and to my fine copy-editor, Sue Phillpott.

As ever, I am also indebted to my now husband John Forrester, who has more facts in his daily repertoire than I can dream of, and my wonderful children Katrina Forrester, Josh Appignanesi and now also Devorah Baum and Jamie Martin, with whom discussion is a constant inspiration.

Lisa Appignanesi was born in Poland, grew up in France and Canada, and lives in London. A novelist and writer, she is Visiting Professor of Literature and the Medical Humanities at Kings College London, Chair of the Freud Museum, and former President of English PEN. She was awarded an OBE for services to literature in 2013. She is the author of Mad, Bad and Sad, All About Love and Losing the Dead.

This is the story of crimes that grew out of passion, their perpetrators, and the courtroom dramas in which they were enmeshed. It is also the story of how medics who became experts in extreme emotion came to probe and assess the state of mind of these passionate transgressors. The cases in question as well as the experts views affected justice and left their mark on history. The views were no more gender-blind than justice itself.

When thirty-one-year-old Mary Lamb, not yet co-author of the long-loved Tales from Shakespeare, murdered her mother in 1796, her brother Charles told the Coroners Court she was mad. This resulted in her being sent home into his care and absolved of all responsibility for her crime. Murder was considered to be an act, not an essence marking her out as a naturally born criminal, an aberrant being tainted by degeneracy from birth as various crime and mind experts might insist a century later. No psychiatric witnesses were called on to investigate Marys state or to give an opinion in court. The determination of her lunacy was everyone agreed visible to a common-sense appraisal by coroner and jury. Sifting what and who was bad from what and who was mad took no expert training. Roman Law enshrined a principle of mitigation for those who were non compos mentis of unsound mind and not in control of their mental faculties. English common law followed suit: law-breakers with a defect of understanding, such as children, or a deficiency of will, such as lunatics, could not be held accountable for their acts. Madness was its own worst punishment; Mary Lamb needed no additional one.

In the course of the nineteenth century and into the beginning of the twentieth, such rulings took on the growing complexity we recognize as the norm today. The line between who was mad, who bad, grew more opaque and began to waver. If justice was to be done, an untrained eye could not be trusted to make the judgement. This required the expert opinion of mad-doctors and alienists (the keepers of people whose reason has been alienated), nerve medics and those who by the turn of the century as the profession proliferated had started to become known as psychiatrists. Theirs was an expertise founded on the very passions that sweep reason away, on vagrant emotions and erratic cognitive powers, on manias, delusions, delirium and automatisms. Their knowledge could serve the courts and inform justice, as well as protect society. Disseminated from debates in the courtroom through an ever more popular press, their thinking also subtly changed our view of the human.

A Pandoras box flew open as psychiatric experts and a sensationalizing media probed motivation in a variety of murder and attempted-murder trials. Transgressive sexuality, savage jealousies, rampant forbidden desires, passions gone askew, vulnerable, suggestible, hysterical minds, were revealed to be aspects not only of those others we label mad, but potentially of us all. When humanity dreamt collectively as Robert Musil noted in The Man Without Qualities, his novel about the year that led into the Great War it dreamt a Moosbrugger, a sadistic pervert, a psychotic murderer who wore an everyday aspect of mild good citizenry, a face blessed by God with every sign of goodness.

Next page