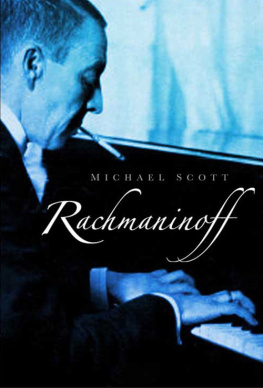

Rachmaninoff

For Michael and Pamela Hartnall

Rachmaninoff

MICHAEL SCOTT

First published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

Michael Scott, 2008, 2011

The right of Michael Scott, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7242 3

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7241 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Music, like poetry, is a passion and problem

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Acknowledgements

I should particularly like to thank many friends over the years who have generously helped me in countless different ways: Michael Aspinall of Naples who has given me the benefit of his erudition and knowledge; Gregor Benko of New York who has been unstinting in his efforts to secure information; the late Richard Bebb and his peerless collection of recordings and memorabilia; Jack Buckley; Peter G. Davis of New York Magazine; Nicholas Hamer of Mauritius for his unstinting generosity and exceptional patience; Michael and Pamela Hartnall; Stephen Hastings, Editor of Musica; the late Jack Henderson who went to Rachmaninoff recitals; the late Joel Honig; Francesco Izzo; the late Frank Johnson, Editor of The Spectator; Vivian Liff; Bert Luccarelli; Guthrie Luke, pupil of Alfred Cortot; Barrie Martyn, author of Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor, and his wife Alice, who graciously invited me to their home before we had even met; Liz Measures; Andy Miller and Karen Christenfeld of Rome; Joel Pritkin who sent me photographs of Rachmaninoffs last Californian residence; the late Patric Schmidt of Opera Rara; Randolph Mickelson who entertained me at his homes in Venice and New York; Mary Tzambiras; John Ransley; my brother John and sister-in-law Coby who invited me to Riga; my sister Edith and brother-in-law Philip; Robert and Jill Slotover; Robert Tuggle, Archivist of the Metropolitan Opera, New York; the late Professor L.J.Wathen of Houston; Raymond A.White of the Library of Congress, Washington; and last, but not least, to Robert Dudley. I am also grateful to Christopher Feeney, Jim Crawley, Sophie Bradshaw and Kai Tabacek of The History Press.

I have transliterated Rachmaninoff the way he did himself, that is in the French style, as I have done with Chaliapin, Diaghileff, Baklanoff and Tchaikovsky. With other names I have preferred familiar spellings. Inevitably this has led to inconsistencies, but then English is irregular and systems are inapplicable.

Preface

Rachmaninoff was the last in the tradition of the great Romantic composer pianists that had developed through the nineteenth century, from the days of Chopin and Liszt. By his time, the increasing complexity of music had led to a growth in the size and importance of the orchestra which demanded another new type of virtuoso: the conductor. Whereas before the revolution in Russia Rachmaninoff was well known as a conductor, after it, exiled in the west, he turned to the piano and to composing, and hardly ever conducted. Another, from our point of view today, more revealing respect in which he differed from his predecessors is that he lived into the age of recordings, and as well as his music we now also have records of him as a pianist and conductor. They have something interesting to tell us, not only about his own compositions, but they are hardly less illuminating for the light they throw on the interpretation of Romantic music generally.

By the First World War, even in a society as reactionary as imperial Russia, his compositions reflected a musical style that had already become pass. His records shed light not only on his own compositions, but on the interpretation of Romantic music generally. There is a paradox contained in the fact that although critics sniffed at his compositions, especially after he moved to America and western Europe, the public continued to admire them inordinately. It is revealing that notwithstanding the Depression, the concerted works he played were almost always his own compositions.1

Today, more than sixty years have passed since his death and his music has become a part of the concert repertory; his reputation as a composer has been restored. In 1918 when he began his career as a piano virtuoso, aside from his own compositions, his repertory was of the narrowest kind. He played only a few token works from the Classical period (often arrangements or paraphrases) and rarely played anything more modern than the works of Scriabin and Medtner. Looking over his concert programmes today, much in them may seem insubstantial or overfamiliar. We might feel tempted to accuse him of cynicism or of having his eye on the box-office. There was no need for him to adapt his playing, as every pianist must today, to the many divergent musical styles that are now available.

As soon as he touches the keys he immediately establishes his own personality, yet he does not obfuscate by imposing himself on the music; rather, he illuminates. His performance style comes in marked contrast to what we may expect, thinking of his music; his records will certainly surprise those who confuse Romantic with self-indulgent. In 1927, Olga Samaroff, herself a distinguished pianist, wrote: Rachmaninoff seldom displays in my opinion the emotional warmth and sensuous colour so characteristic of his own creative muse.2 By then it was not his playing but the conception of what constituted the Romantic style that had changed. Romantic music was fast going out of fashion, its style becoming decadent. For Rachmaninoff, the popular Romantic classics were neither exhausted by the incessant replay that electric media has exposed them to, nor alienated by the introduction of a new, unsympathetic post-Romantic style. Recordings of him conducting and playing the piano remind us how illogical it is to believe that a period so rich in the creation of great masterpieces did not know how to interpret its own music.

They reveal two telling aspects of his technique: his command of dynamics and his rhythmic control. In the last three-quarters of a century, just as amplification has gradually corrupted our appreciation of dynamics, so the overwhelming influence of Afro-American jazz has introduced a narrower, more literal sense of rhythm. His records remind us that virtuosity is not just a question of not playing any wrong notes but of playing the right ones in the right places.

One no sooner reflects that perhaps the most fabulous aspects of his piano playing were his melodic eloquence and dramatic virtuosity, than one remembers the unique rhythmic bite in sustained, short or syncopated accentuation, or his way of orchestrating chords with special beauty through individual distributions of balances and blendings.3 He use[d] the pedal dexterously in his production of light and shade he [did] not abuse this device; indeed he [wa]s often austere in the niceness with which by a perfection of timing, he released the sustaining pedal to avoid dissonance.4