Einsteins Mistakes

THE HUMAN FAILINGS OF GENIUS

Hans C. Ohanian

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY| NEW YORK | LONDON

Copyright 2008 by Hans C. Ohanian

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ohanian, Hans C.

Einsteins mistakes: the human failings of genius / Hans C. Ohanian.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07042-2

1. PhysicsHistory. 2. PhysicsPhilosophy. 3. ScienceHistory. 4. Einstein, Albert, 18791955. I. Title.

QC7.033 2008 530.09dc22

2008013155

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

TO MY OLDEST FRIEND

E RRORS ARE THE PORTALS OF DISCOVERY .

James Joyce, Ulysses

Preface

T his book is a forensic biography that dissects Einsteins scientific mistakes. It deals only tangentially with the mistakes in his personal life, which have already been sufficiently exposed by some of his biographers. And it does not deal at all with the mistakes that misguided souls imagine they perceive in his theories of special and general relativity. It focuses, instead, on the missteps that Einstein made in his search for his theories and the misconceptions he had about some of the subtleties of his own creations. These mistakes in his scientific work are less well known than the mistakes in his personal life, but they are ultimately more important. As Einstein himself said, What is essential in the life of a man of my kind lies in what he thinks and how he thinks, not in what he does or suffers.

The several years I spent exploring Einsteins mistakes were an exciting and enjoyable experience for me. Not, I hope, because of Schadenfreude (roughly translated as gloating, but gloating is a behavior, whereas Schadenfreude , literally joy of harm, is an emotion; it is an almost uniquely German word, with an exact equivalent only in Chinese). But, rather, because these mistakes made Einstein appear so much more human. They occasionally brought him down from the Olympian heights of his great discoveries to my own level, where I could imagine talking to him as a colleague, and maybe bluntly say, in the give-and-take of a friendly discussion among colleagues, Albert, now that is really stupid!

For my research on Einsteins mistakes, I relied on primary sources, that is, his own books, papers, lectures, and letters (many of them printed in The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein ). However, for the biographical and historical background, I relied more heavily on secondary sources, such as the excellent and well-balanced biography by Albrecht Flsing.

The translations from German to English are my own, because I found that existing translations are often unreliable. In casual remarks and in letters, Einstein often used colorful idiomatic expressions, and translators not thoroughly familiar with the German vernacular have taken pratfalls over these ( traduttori , tradittori , say the Italians). Two examples will illustrate the point. Einsteins famous pronouncement Raffiniert ist der Herrgott aber boshaft ist Er nicht is commonly translated as The Lord is subtle, but not malicious, and Abraham Pais even used this translation as the title for his biography of Einstein, Subtle is the Lord . As a German speaker, Pais should have known better. The German word raffiniert has a rather negative connotation; its correct translation is cunning or crafty, and thus, The Lord is cunning, but not malicious. Another amusing example is the comment that Einstein made about Marie Curie, describing her as a Hringseele , which is usually mistranslated as having the soul of a herring. Despite its etymology, Hringseele does not mean there is something fishlike about a person; it is merely an epithet for a lean, gaunt, or meager person. Hence Einsteins comment, Frau Curie ist sehr intelligent, aber eine Hringseele , das heisst arm an jeglicher Art Freude und Schmerz translates as Frau Curie is very intellient, but meager in emotion, that is to say, impoverished in any kind of joy or pain. Poor Mariein France she was pilloried for her affair with Paul Langevin, and in the English-speaking world she was filleted as a fish.

I thank several friends and colleagues who read the manuscript and provided helpful comments. Also, I thank Angela von der Lippe, my editor at W. W. Norton, who tried her best to keep me from making a fool of myself. If she did not succeed, it is entirely my own fault.

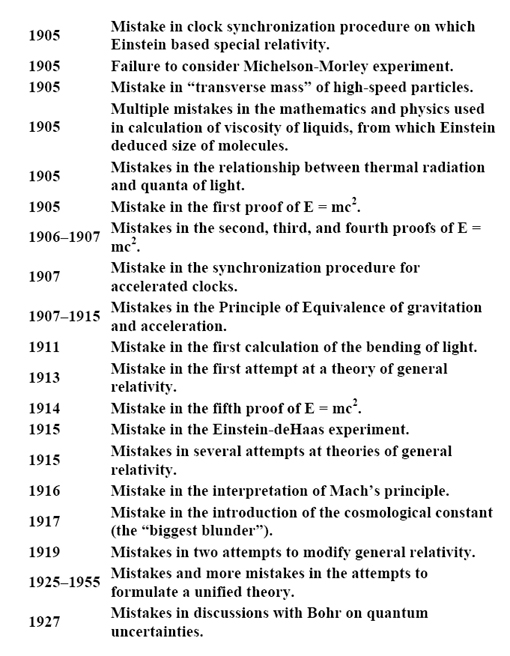

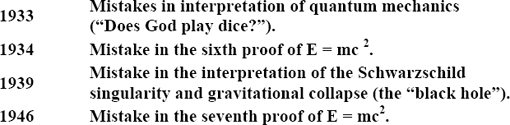

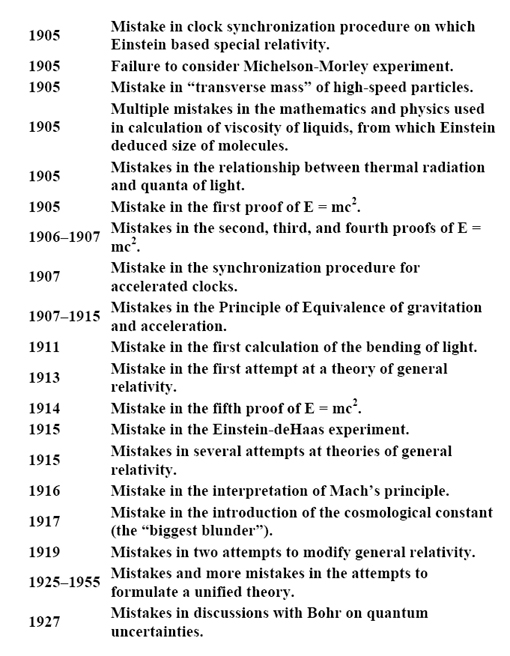

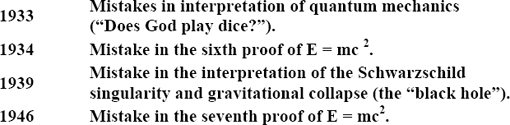

Chronology of Einsteins Mistakes

Prelude

I will resign the game

O n Tuesday, June 24, 1969, Albert Einstein drove Donald Crowhurst into madness. Crowhurst was a participant in the single-handed around-the-globe sailboat race organized by the Sunday Times of London, and he was alone in his trimaran Teignmouth Electron , becalmed in mid-Atlantic, in the Sargasso Sea, about 700 miles southwest of the Azores. There were no eyewitnesses to his descent into madness, but we know what happened because he meticulously recorded the events in his logbook. On that fateful day, he began to read Einsteins book Relativity, The Special and the General Theory . The book was first published in 1917, just before Einstein became a celebrity, and it explains his theories in more or less nontechnical terms. It sold a great many copies, went through fifteen editions, was translated into a dozen languages, and is still in print. Most of these copies remained mostly unread, butlike the currently fashionable books by Stephen Hawkingthey presumably added some cachet to the private libraries of intellectuals and their fellow travelers.

Crowhurst had stowed the book, and a few others, aboard his yacht to while away long boring days with no wind. He was an electrical engineer, and his training in mathematics and physics was certainly adequate for coping with this book. After reading a dozen pages, he came across a paragraph that, quite literally, blew his mind. Einstein proposed to test the simultaneity of two eventssay, two lightning strokesat two widely separated points A and B by observing the arrival of light signals from these events at the midpoint between A and B . Discussing the travel times of the light signals from the points A and B to the midpoint M , Einstein claimed:

That light requires the same time to traverse the path AM as for the path BM is in reality neither a supposition nor a hypothesis about the physical nature of light, but a stipulation which I can make of my own free will in order to arrive at a definition of simultaneity.

Crowhurst simply could not believe this. He knew thatbecause of the motion of the Earthit was by no means self-evident that the speed of light relative to the Earth would be the same in all directions, and he thought it outrageous that Einstein would pretend to settle this question by stipulation. In his logbook he wrote:

I said aloud with some irritation: You cant do THAT! I thought, the swindler. Then I looked at a photograph of the author in later years. The essence of the man rebuked me. I re-read the passage and re-read it, trying to get to the mind of the man who wrote it. The mathematician in me could distinguish nothing to mitigate the offending principles. But the poet in me could eventually read between the lines, and he read: Nevertheless I have just done it, let us examine the consequences.