ALSO BY RICHARD ASKWITH

Feet in the Clouds: A Tale of Fell-Running and Obsession

Running Free: A Runners Journey Back to Nature

Copyright 2016 by Richard Askwith

Published in the United States by Nation Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor

New York, NY 10003

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address the Perseus Books Group, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Nation Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Typeset in India by Thomson Digital Pvt Ltd, Noida, Delhi

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

LCCN: 2016933228

ISBN: 978-1-56858-550-5 (e-book)

Published in the United Kingdom by Yellow Jersey Press,

an imprint of Vintage,

20 Vauzhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

UK ISBN: 9780224100342

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

Photo section appears after

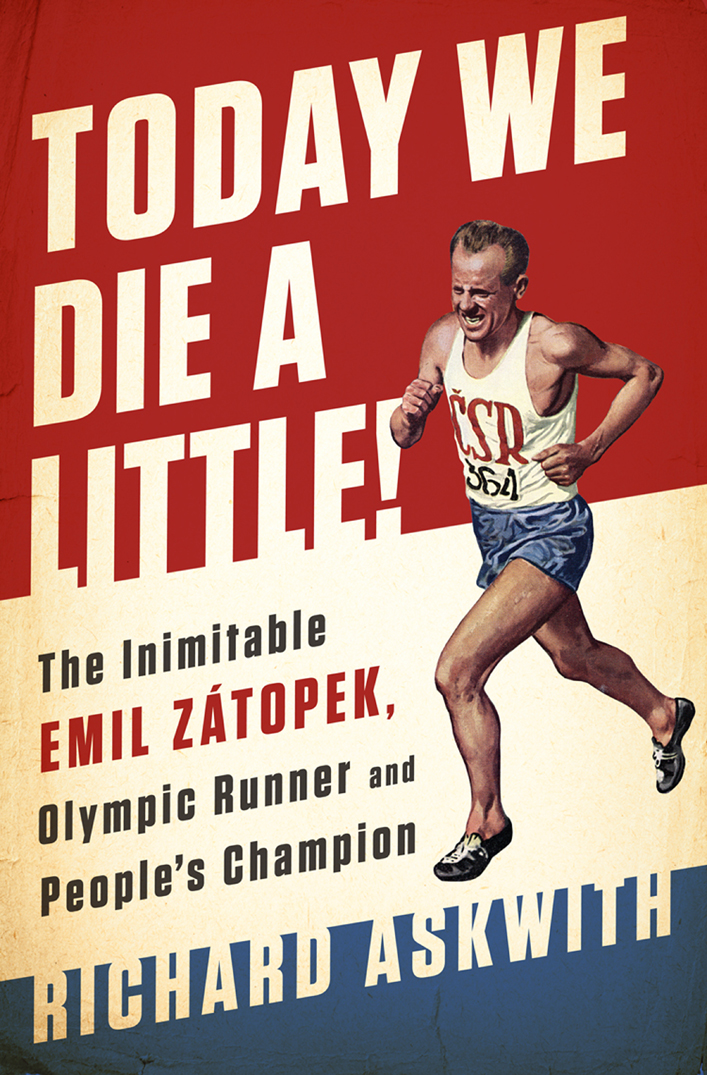

O n a sun-scorched runway in Prague, a twin-engined eskoslovensk Aerolinie airliner is waiting for take-off from Ruzyn International Airport. More than a hundred young men and women, the finest athletes in the Communist state of Czechoslovakia, are bound for Helsinki, a seven-hour flight away, where the XVth Olympic Games will begin in nine days time. But there is a problem. The brightest and best of them all, Emil Ztopek, is absent.

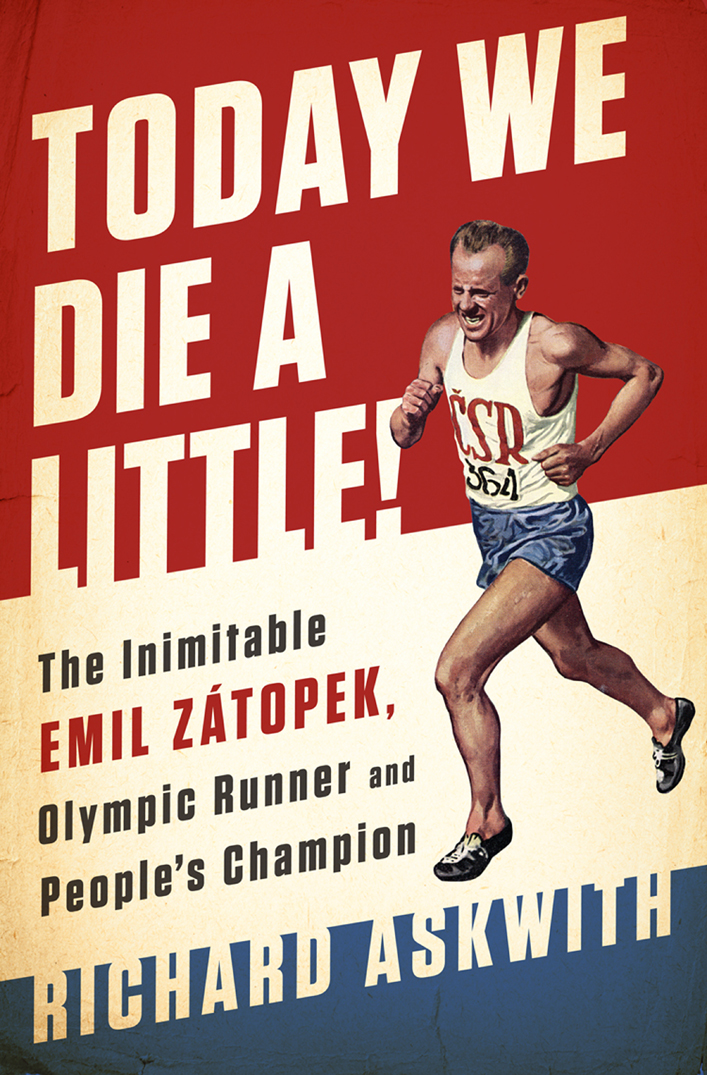

The greatest runner of his generation perhaps of all time is missing from the flight that is due to take him to the Games that will define his sporting life. He is at the height of his powers: twenty-nine years old, a world record holder, a reigning Olympic champion who has lost only one of his last seventy races at his specialist distances, with his sights set on an unprecedented and never-to-be-repeated clean sweep of endurance running events.

It is the most important journey of his life. And he is late.

At least, that is how it looks. Emils wife, Dana, knows better. A javelin thrower with Olympic ambitions of her own, she is on the plane already, weeping. She knows the real reason why Emil is not beside her. She knows that he is engaged in a high-stakes game of chicken that could not just end his career but quite plausibly see him sent to a labour camp.

It is Thursday, 10 July 1952. The Iron Curtain that fell across Europe at the end of the Second World War has grown more oppressive in recent years, especially in Czechoslovakia. The Communists seized power there in 1948; a ruthless secret service, the Sttn bezpenost (StB), has helped them keep it. By 1950, show trials had begun. The most notorious, the Slnsk trial, is still being prepared, but already scores of enemies of the revolution, real and imagined, have been executed. Tens of thousands are under surveillance by the StB. And now, with the Soviet Union preparing to take part in its first ever Olympic Games, the shadow of Stalin looms ever larger over Czechoslovak life literally so in central Prague, where the worlds biggest statue of the Soviet dictator, eventually to be nearly thirty metres high (if you include the base), is under construction.

No one is immune from the obsessive and brutal enforcement of political conformity. Athletes of all kinds have been among those rounded up in the purges. You dont have to be guilty of anything: just out of favour. It is less than eight months since the entire national ice hockey team was arrested, on the evening of its departure to London to defend its world title. Twelve players were condemned to camps for, supposedly, contemplating defection (and, in some cases, singing disrespectful songs); the combined total of their sentences was seventy-seven years and eight months.

By those standards, the problem with Stanislav Jungwirth, Emils teammate and a future 1,500m world record holder, is a trivial one. Stanislav himself is not in trouble. It is Emils response to the problem that is potentially catastrophic. Stanislavs father is in prison for political offences and that, the Party has decided, makes it inappropriate for Jungwirth junior to travel abroad, except to other Warsaw Pact countries. It is a modest restriction; unless, like Jungwirth, you are an Olympic athlete who has spent the past four years dreaming of Helsinki.

News of Jungwirths exclusion emerged the evening before the athletes were due to fly, when they turned up at the Ministry of Sport to collect their travel documents. Jungwirth was devastated to find that there were none for him, but quickly accepted that making a scene would only make matters worse. But Emil was incandescent. No way, he told the officials. If Standa does not go, nor will I. Then he stormed out, leaving his paperwork behind him.

The next day, on the morning of the flight, Jungwirth implores Ztopek to calm down. Emil insists on standing his ground. He gives Jungwirth his team outfit and tells him to return it to the Ministry when he returns his own. Then he goes off to train alone at Pragues Strahov stadium.

The stand-off continues for days, by which time the plane has long since left without Ztopek. Dana is inconsolable: the stress causes her to lose her voice. It is barely a decade since her own father was taken away by the Gestapo during the German occupation; he ended up in Dachau. Now her husband seems to have condemned himself to a comparable fate.

In Helsinki, Western journalists are told that Ztopek has tonsillitis.

* * *

More than seventy years later, on a wet Wednesday evening in January, I am sitting in an aeroplane on that same runway. It is a Wizz Air flight this time, delayed for well over an hour by one of those inscrutable problems to which budget flights are prey. Our destination is London Luton, and the passengers, far from being Olympic athletes, are mostly price-conscious tourists. But my head is full of thoughts of Olympic glory in Helsinki.

I have spent the past few days visiting Ztopeks old haunts and talking to people who knew him; the highlight was a long morning of memories, laughter and slivovice (plum brandy) with Dana herself. Now, on the homeward journey, I have just reached the end of my second Ztopek biography of the week and am wondering which one to begin afresh. They are all the reading matter I have, and today there have been many hours to kill.

The engine starts to hum with pre-take-off half-life. The air crew perform their safety drill, and I note with pleasure that I recognise several words. Maybe that teach-yourself-Czech audio programme is starting to work. Then I find myself thinking about the Jungwirth incident. I wonder if the puddled runway I can see through the window bears any resemblance to the view that Dana saw as she scanned the asphalt fretfully through an aeroplane window in the summer of 1952, wondering if Emil would appear.

Next page