SATELLITE

SATELLITE

INNOVATION IN ORBIT

DOUG MILLARD

REAKTION BOOKS

Published in association with

the Science Museum, London

To Mum and Dad who encouraged me then;

Stephanie, Edward and Daniel who encourage me now

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

In association with the Science Museum

Exhibition Road

London SW7 2DD, UK

www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

First published 2017

Text SCMG Enterprises Ltd 2017

Science Museum SCMG Enterprises Ltd and logo design SCMG Enterprises Ltd

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780237060

CONTENTS

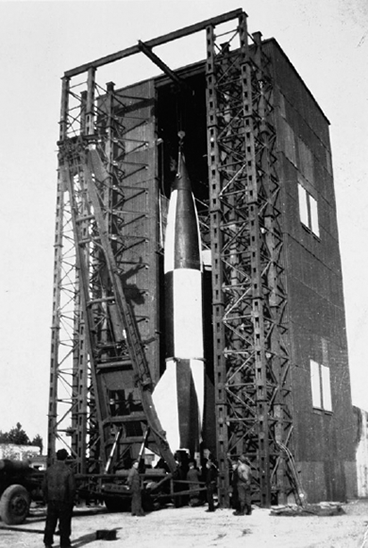

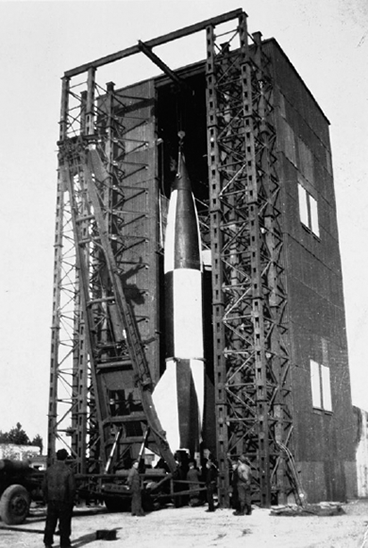

V-2 rocket on launch pad, Operation Backfire, Cuxhaven, Germany, 1945. Operation Backfire was a British post-Second World War operation designed to evaluate the V-2 rocket system.

INTRODUCTION

I t is a truism, and a clich, that we have gazed at and wondered about the heavens since time immemorial. Many an exhibition or even book on space starts with such a statement. The ancient civilizations of Greece, Mesopotamia, India, China and Central America are all likely to be cited as centres of cosmic observation and investigation. In modern times Jules Vernes voyages to the Moon in his literary marriages of fantasy and rationalism are likely to feature too. His contemporary of the nineteenth century, Giovanni Schiaparelli, showed us drawings of Mars that hinted at intelligent life on the red planet. We thought afresh of how to reach these places in space. How would we get to Mars? How could we break the bonds of gravity and reach other worlds?

Some did the maths. They calculated how space flight could be achieved, how fast they would need to go to get into space and by using what type of vehicle. The first step would be to make it into Earths orbit. You would use a rocket, in stages that fell away as each exhausted its fuel supply. Your rocket would grow lighter as each load detached, and accelerate on to a velocity of 8 km per second. Then your speed would be balancing Earths pull of gravity and round and round you would go, falling perpetually around Earth as a new moon; a new satellite.

From there a staging post in orbit you could depart to the planets and beyond. The rocket would be huge and use exotic, energy-rich propellants; the gunpowder and fireworks that had been around for centuries had merely showed the way. Within decades of such predictions large space rockets were with us, not aiming for space but raining death and destruction onto tens of thousands. The 10-metre-high V-2 rocket of the Second World War was aimed at London but touched space as it climbed ever higher before falling on to its civilian target. Hot war gave way to cold war, and a geopolitical impetus for launching satellites grew as a means of demonstrating the technological superiority of the launching state. They would also be able to conduct scientific investigations, relay television signals around the world, and especially so gather intelligence on ones enemy. The first was Sputnik, launched by the Soviets and opening an age of space in which we continue to dwell... except we no longer appreciate it. At first satellites were headlines, prestige that dazzled. Now they are invisible, yet vital; ubiquitous yet mysterious.

The satellite is a reticent technology. Our modern world depends on them just as much as the computer, the automobile or the aircraft. We use it to farm, to carry out financial transactions, for moving around the globe, for generating energy, for monitoring the weather and climate, for security and scores of other functions. The satellite is essential.

The story of the satellite is remarkable. Its diffidence cloaks an astonishing history of imagination, experiment and ingenuity. Its history traces the formative years and events of the tumultuous twentieth century. This book unveils the satellite, once trumpeted as the future present, anew. What forms has it taken? How did the forms evolve and why? Who required them? What exactly do satellites do and how? And what larger picture are satellites part of? The satellite was a first step on a road to the stars. We have walked on the Moon, but Mars that catalyst to the imaginations of the early space thinkers remains for the future. We are content to stay mainly in Earths orbit, peering across the cosmos through space observatories, or sending satellite emissaries to other planets and their moons. The pioneering satellite Sputnik and its successors help us on Earth and extend our place in space but pose questions, too, of how far we choose to extend that existence.

explores the history of the satellite as a concept of the mind; of how thinkers well before Sputnik, or indeed space rockets, envisaged an object that could travel endlessly around our planet (and others). It taps into those minds that worked out how to reach space and thence the planets; for these theorists, satellites would act as the staging posts in Earths orbit for interplanetary voyages. Isaac Newton developed the necessary mathematics of the motions involved; two centuries later the Russian schoolteacher Konstantin Tsiolkovsky calculated the speed and means needed to take that first step into Earths orbit using powerful new rockets. Come the twentieth century and such thinking was invigorated in a period of frantic technological development, via revolution and warfare, when the rocket, no longer just a firework and indiscriminate battlefield weapon that scared the horses and burned down cities, was given enormous power and precision. The German V-2 rocket of the Second World War terrorized and killed thousands, yet pointed the way into space in a manner that the visionaries had long dreamt.

it was assumed by many in the post-war world, would be American; its affluence and technological might was surely a guarantor for it being the first nation to reach space. This was not to be. The first artificial satellite of the Earth was launched by the Soviet Union in 1957, while the U.S. floundered on the launch pad.

examines the frantic early years of the space age. Reaction to Sputnik was intense, particularly so in the U.S., where Soviet satellites were now perceived as a military and political threat. The U.S. reinvented its muddled satellite programme with new agencies geared to putting the nation firmly in orbit and then on to the Moon. In the USSR a record of space firsts was maintained, and extended to putting the first manned satellites into orbit. Both nations were now fighting a proxy war in orbit, with space a political tool for the competing geopolitical ideologies. For others, satellites became the epitome of a space-age cultural and consumerist trend that marked the arrival of the future.

In the closing period of the Second World War, a young English serviceman wrote of a means by which television, the first public service being little more than a decade old, might unite the world with transmissions beamed via satellite. Twenty years on and this dream of Arthur C. Clarkes materialized with the first satellites launched into the eponymous Clarke orbit. order to provide locations at sea for nuclear submarines, with accuracy to a few metres) and found wide use by all of the armed services. The Global Positioning System, or GPS as it came to be known, was made available to civilian users, so contributing to a developing reliance by societies on all forms of satellite.