Venice for Lovers

for Nicholas, Julia,

Isabella, Henri and Jacob

Venice for Lovers

Louis Begley

Anka Muhlstein

Copyright 2003 by Louis Begley and Anka Muhlstein English translation copyright 2005 by Anne Wyburd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in

any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the

facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval

systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except

by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any

members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or

all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to

obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should

send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway,

New York, NY 10003.

Originally published in German by marebuchverlag,

in Hamburg, Germany in 2003 as Les Clefs de Venise

First published in English in Great Britain

in 2005 by Haus Publishing Limited, London

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9869-3

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

Contents

by Louis Begley and Anka Muhlstein

by Anka Muhlstein

by Louis Begley

by Louis Begley

Preface

Beginning in 2001 or early 2002, we were asked repeatedly by the publisher of the German version of this volume, who knew our deep attachment to Venice, and liked our work, whether we would jointly write for a book about it for him. We answered always that we are not travel or guidebook writers, and that, in any event, we do not write together. Anka is a historian and biographer; Louis is a novelist. She writes in French, and he writes in English. We did not think that such a thing could be done. In addition, we pleaded commitment to other projects, a solid reason, especially since Louis was then still practicing law full time. The publisher persisted. In the spring of 2002, the text of a speech Louis gave at a benefit event for Save Venice, a charity devoted to the protection of Venetian monuments, came into our publishers hands.

We have the kernel, he told us, the kernel of your book. That kernel was, in somewhat different form, the essay about the use novelists have made of Venice, which is the third part of this volume. All we need now, our publisher continued, is a very personal piece by Anka about her Venice, and a short story with a Venetian theme by Louis.

And so the book took shape.

It was by then summer. Anka had finished the research for her Elisabeth I et Marie Stuart ou les prils du marriage, which appeared in October 2004, and was only beginning to write. Louis had almost completed his most recent novel, Shipwreck. The charm and wiles of our publisher prevailed. We agreed to this most unusual project, a work by a French and an English- speaking writer that would initially appear in German.

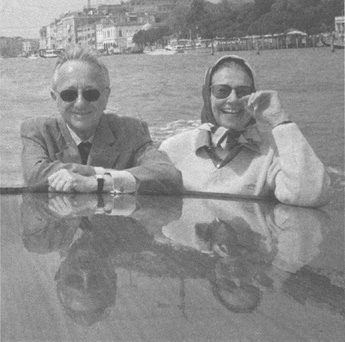

We have reconsidered and revised our pieces for this English edition. A writers work is never done; we could have gone on revising forever. One always feels that one should. But then no work would come to be published. We stand by what we wrote two years ago. The experience of Venice is an intensely personal one, if only because la serenissima is so mysterious and wins one over so completely. That is what we have tried to convey in our very different ways. We have also hoped to infect our readers with our own love for Venice, which runs very deep, and has brought us great happiness.

Anka Muhlstein

Louis Begley

The Keys to Venice

by Anka Muhlstein translated by Anne Wyburd

For the last 20 years we have spent a fortnights holiday in Venice each year either in the autumn or the spring holidays which over the years have acquired Colettes meaning: a holiday is working elsewhere, because during these periods in Venice my husband has been able to write without incessant interruptions. He has the enormous advantage of being a novelist and having everything in his head. I, poor biographer, need books, dictionaries and encyclopedias for my work. Since we hate travelling with a portable library, I do not always write there, but I read, correct and rewrite. This has not always been the case. Before Louis started writing in 1989, we spent long periods walking, losing our way, looking at pictures, going to concerts or negotiating to get into places closed to tourists like us. Among our triumphs we count a visit to the Biblioteca Marciana to see the first editions of Dante won after claiming a completely imaginary friendship with the director of the New York Public Library and an hour spent in the Baptistery of Saint Marks, accompanied by a functionary of the basilica who was moved by our supplications, and gracious enough to respond to our thanks by saying that our pleasure in contemplating his treasures consoled him for the spectacle of the troop of tourists - la gregge di pecore (the flock of sheep) who invaded his church, shuffling their feet and damaging the wonderful pavement. But we did not always succeed. During the years when the doors of San Sebastiano only opened for a brief mass and no exceptions permitted, the guardian of San Sebastiano was impervious to our charms, our pleas as visitors from afar and our passion for Veronese. The porter of the Patriarchal Seminary and the guardian of the Conservatory were equally intransigent.

Step by step we got to know the city, until I no longer needed to walk about with a map in my hand. First of all I knew that, contrary to what I had thought to begin with, it is impossible to get lost in Venice one only has to follow the flow to find oneself back under the clock tower in Saint Marks Square or at the foot of the Rialto Bridge and then I had my landmarks: a shop window, a sign, a stone lion guarding a balcony, a sculpted door reminded me where to turn. In fact the game now consisted in following non-tourist itineraries and avoiding Saint Marks and its surroundings before 6 pm. If one wanted to go into the Basilica one had either to attend Vespers or to slip in by a side entrance, put on a solemn face and explain to the doorkeeper that one had come to say ones prayers. The walk towards Santa Madonna dellOrto involved discovering a silent Venice populated by housewives, children and old people in slippers, and a stroll along the Canareggio meant experiencing a more active, working-class Venice. San Francesco della Vigna or the far side of the Arsenal also offered campi where passers-by walked with the quick, decisive step of local residents, expert at avoiding the flights of ubiquitous footballs. Venice had become familiar to us; our first slightly frenetic curiosity had been satisfied. Working in the afternoons (we always devoted our mornings to walking) was the sign that we were now at home in Venice. We had changed, but one of our principles had remained unaltered: we did not want to meet anybody.

Trailing through the alleys of the city in a group while checking that everyone else was following, making appointments which were doomed to be missed, because someone would make a mistake over the vaporetto (the 7 has become the 82 and the landing-stage has been moved, they would explain pathetically), while others would confuse the Gesuati with the Gesuiti, the Palazzo Bembo with the Bembo-Bold or even the Palazzo Contarini with the Contarini-Fasan, the Contarini-Michiel or any of the six other Contarini palaces, spending the evening gossiping or talking politics with friends we see all the time in New York or Paris while one is absorbed in ones real or fictitious characters no, we did not want that. Of course, it is foolish to think one can avoid people completely in this very small town. We were lucky to have an alibi in the charming person of one of our nieces who had settled in Venice. Any attempt to suggest a meeting was countered with I am so sorry, we are dining or lunching, or taking tea with Marie. So we continued to see nobody except those we saw every day and even twice a day - that is, the proprietors and head waiters of the restaurants we frequented.

Next page

![Bosworth - Italian Venice: a history[Electronic book]](/uploads/posts/book/194557/thumbs/bosworth-italian-venice-a-history-electronic.jpg)