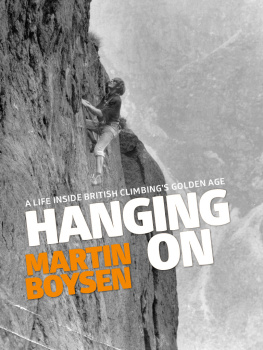

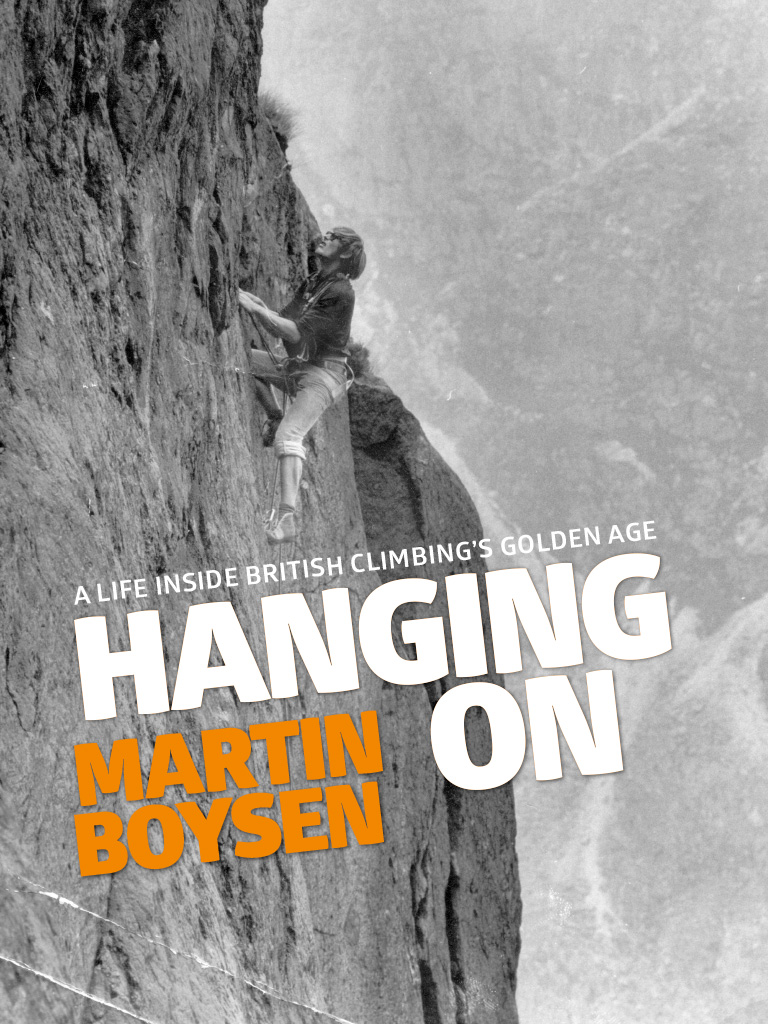

I should like to thank the many friends and members of my family who have encouraged me to complete my book. I am particularly grateful to those who so generously offered the photographs for the book. In particular I owe my gratitude to Susan Czerski who managed to transform my scrawl into legible print and to all of the publishing team at Vertebrate.

Me as a child in Alsdorf, Germany.

Photo: Boysen collection.

My earliest memories are the wailing of air-raid sirens followed by the droning of Lancaster bombers and the distant thump of high explosives. I was always the first to wake and initiate the rush to the cellars with my mother, older sister and brother, Lorna and Bill. It was our misfortune to be living in Germany in the small mining town of Alsdorf close to Aachen. I was four years old and the war was drawing to its bitter end.

Why we were on the wrong side, stuck in Germany, perhaps needs to be explained. My mother was English, but my father was German. They had met each other when my father was a student on an exchange visit to England as part of his degree in English and music at Cologne University. He lodged at my grandmothers house in the village of Pembury near Tunbridge Wells in Kent. My parents fell in love and my mother became pregnant out of wedlock. This caused a dreadful stir in the village where my grandmother was a pillar of the community and my grandfather the owner of the village grocers.

The relationship between my grandma and my father, somewhat sarcastically referred to as dear Jens, was never going to be easy and at the time of Lornas birth it was understandably at an all-time low. After a quiet wedding in the old village church they fled to Germany where my father began his teaching career and the young newly-weds established their first home. We became a comfortably-off, middle-class family with three young children and my father starting in his first good job. Unfortunately my parents, along with most other intellectuals, were unconcerned or unaware of the stealthy advance of the Nazi party. Hitler had been a figure of amusement before he held the reins of power. Germany advanced on its nightmarish course.

I was born in 1941, when the Allies might so easily have lost the war. It must have been a nerve-wracking time for my mother. Contemporary photos and letters reveal the desperation of events; the increasing frequency of bombing raids, the lack of food, the struggle to stay alive. My father was enlisted in the Wehrmacht at a late stage and sent to the Eastern Front. I have no memory of him from this time. Indeed, I would not see him until five years after the war had finished.

We survived as a family hunkered down in our cellar, wisely refusing to uproot ourselves to a supposedly safer location. During the last desperate days before all communication from the outside world ceased the fateful black-rimmed letter arrived. My father had died heroically for the Fatherland. My mother was strangely unconvinced by this terrible news, perhaps because my father had intimated his intention of staying alive and surrendering to the Russians at the first opportunity. His chance came in 1943 as the German offensive into the Kursk salient collapsed and the Soviet Union seized the initiative on the Eastern Front.

He was lucky to survive the first harrowing forced marches to prison camp in the Ukraine but once he arrived he was treated surprisingly well considering the atrocities committed by the German forces on the Russians. He was soon segregated from the hardened Nazis, given the task of forming a camp orchestra, and subjected to re-education, a gentle form of brainwashing, which worked extremely well. My father had been politically naive before the war, but like many other unworldly intellectuals, he became a devoted Communist and remained so until his death. For many years after his return from prison camp we received Soviet newsletters and magazines warmly glorifying the happy workers presided over by smiling Uncle Joe.

As the war finally drew to a close, it seemed a miracle that the whole family had survived then tragedy struck. Aachen and the surrounding area was one of the first parts of Germany to be liberated by British troops. It was hugely exciting. Hungry children besieged the young Tommies, pestering them for sweets and any spare rations. My eight-year-old sister Lorna somehow caught the attention of a playful 18-year-old soldier, who teased her and pretended to steal her shoe. She demanded it back, advanced to get it and he aimed his rifle and pretended to shoot. Only the gun was not unloaded, as he thought and claimed later at his court martial, and she was shot dead with a bullet through her head.

I was luckily too young to realise exactly what had happened. To me it was just another inexplicable disappearance at a time full of strange happenings. But it was a shattering blow to my mother who had been so strong, resourceful and brave throughout these terrible times. When the Allies took over the administration of the area she was enlisted to help translate and act as co-ordinator. During the course of her duties, she discovered she was on the final list of persons to be sent to concentration camps for punishment in the last desperate days of Nazi bloodletting.

Germany was in a terrible state of ruin. Hardly a building remained undamaged. The roads were potholed with bomb craters. Unexploded shells and grenades were frequently found, and we children played soldiers amongst the ruins, collecting shrapnel as a hobby. Food was scarce but, due to the foresight of local miners, some milk was available; they had hidden the local herd of cows in the mine to prevent their seizure by the retreating army.

It was time for our broken family to return to the relative calm of England, to re-establish itself and await the return of my father from Russia. Passage was quickly arranged. A jeep and driver were made available, and the trip to Ostend began. It was an exciting journey and I particularly remember manoeuvring around countless burnt-out tanks in the narrow forested valleys of the Ardennes remnants of the last-ditch German assault on the advancing Allies. We reached Ostend in the evening and embarked on a troop ship filled with soldiers and sailors happy to have survived the war. I remember being spoiled by the soldiers and offered chocolate, an unknown luxury.

We arrived at Tilbury where my grandfather and his brother, Uncle Arthur, the grocery van driver, awaited in his Austin 7. We were too late for the Dartford ferry so our route was extended through the Blackwall Tunnel and then through the North Downs to Pembury. It was a strange arrival to a house with open fires, my unknown grandma and our odd auntie Aunt Margaret who kept an injured green woodpecker in a cardboard box.

From my earliest days in England I rejoiced in the beauty of the countryside. The house, Valeside, was situated on top of a hill with wide views of the Weald framed by huge silver birch trees. There were forests nearby and almost every day I walked or was pushed by my mad auntie Margaret along sunken lanes and woodland paths where we collected wild fruits, mushrooms, chestnuts and sticks for the fire to heat the freezing house. My mother taught me the names of all the wild flowers and where to look for lizards and slowworms on the sunny roadside banks below our house. The winter of 1947 was extremely harsh; fuel was almost unobtainable, food was rationed and life was not easy. Fortunately my grandfather had a large garden where we kept chickens and rabbits and his allotment provided welcome fruit and vegetables.