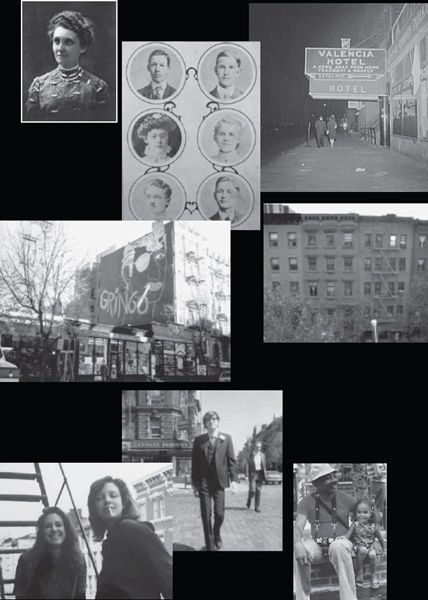

Valencia Hotel, Five Spot, Late Show, St. Marks Hotel, GG Allin

Alexander Hamilton, Jr., Bridge Theater, The Fugss Night of Napalm, Trash and Vaudeville

Khadejha Designs, Gringo mural

James Fenimore Cooper, The Modern School, St. Marks Baths, Mondo Kims

Blind Tom, Carl Solomon, Kristina Gorby

Madame Van Buskirk, Juliet Corsons New York Cooking School, La Trinacria

German Shooting Society, Caf, St. Marks Bookshop

Paul McGregors salon, BoyBar, Coney Island High

Royal Unisex Hair Style

1923 Arlington Hall, Polish National Home, The Dom, The Electric Circus, All-Craft

Limbo,

The Yippies

Slave trader, Mr. Zeros Tub, Manic Panic

East Side Books

Club 57

Joan Mitchell

Leon Trotsky, W. H. Auden, La Palapa

Holiday Cocktail Lounge

Scheibs Place, Jazz Gallery, Theatre 80

William J. Urchs, Little Missionary Day Nursery

9698 Led Zeppelin album cover

Ted Berrigan

Ted Joanss Gallerie Fantastique

Dedicated to my parents,

who looked at the apocalyptic 1970s East Village

and thought, What a great place to raise a kid.

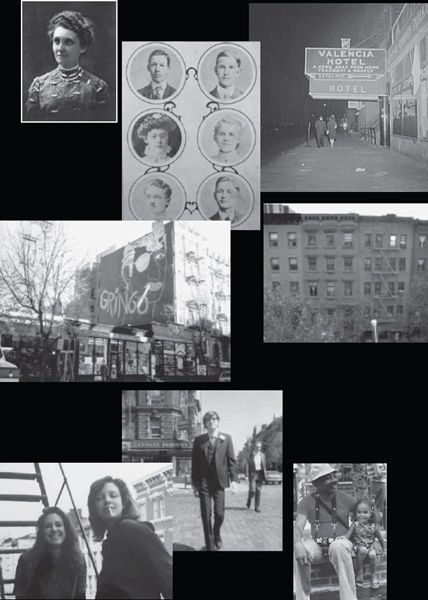

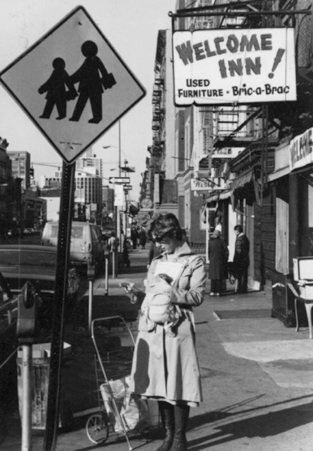

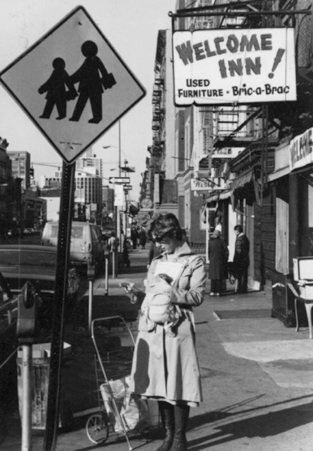

The author and her mother, Brooke Alderson. St. Marks Place

and First Avenue, 1976. Photo by her father, Peter Schjeldahl.

CONTENTS

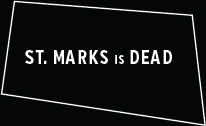

I grew up in Manhattans East Village. My parents have lived in their three-bedroom, top-floor walk-up on St. Marks Place since 1973. I was born in 1976, an only child. As a little girl in the eighties, I navigated sidewalks cluttered with crack vials, used condoms, and junkies on the nod, and witnessed the Tompkins Square Park Riots from my window. As a teenager in the nineties, I bought egg creams at the old-time newspaper shop Gem Spa and hair dye from the punk shop Manic Panic, rented movies at Kims Video, and worked the register at St. Marks Comics.

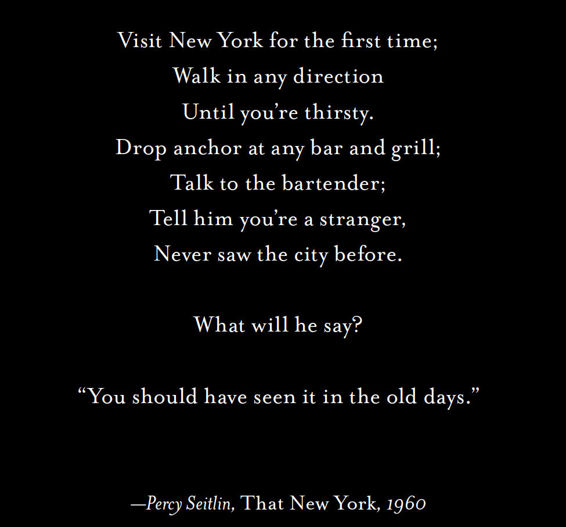

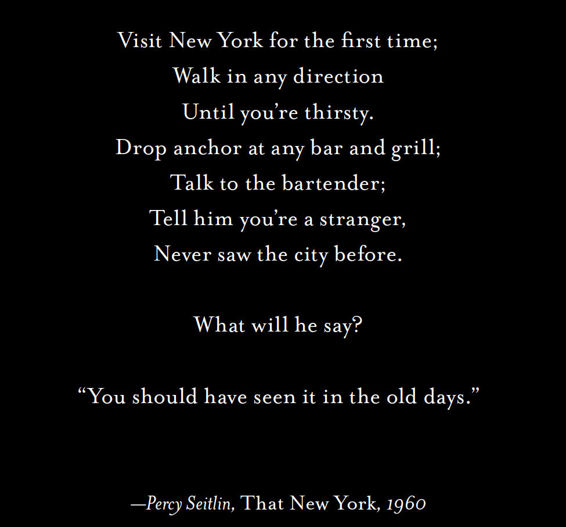

You grew up on St. Marks Place? people sometimes ask, as if they didnt know children could. Or: You grew up on St. Marks Place? implying that I seem too normal to hail from a place with so many Mohawks and tattoo parlors. Then, invariably, these strangers will pity me for having missed the streets golden era, which they identify variously as the 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s.

Theyre right. I missed a lot. I did not love-in or be-in or do anything in. I never sat on a trash can outside the Five Spot jazz club listening to Thelonious Monk. I did not see Andy Warhol introduce the Velvet Underground at the Mod-Dom. I did not hang out with the Ramones or the New York Dolls. Nor did I see W. H. Auden promenade to church wearing his slippers, much less Peter Stuyvesant stumping down the same lane on his silver-and-wooden peg leg.

I am, however, as familiar as a deacons daughter with the religion of St. Marks Place. The street has provided generation after generation with a mystical flash of belonging. Having interviewed more than two hundred current and former residents, I marvel at how many of them describe experiences of mortal peril, dissipation, and misadventure, and then conclude by saying that their era on St. Marksin 1964 or 1977 or 2012was the best time of their lives.

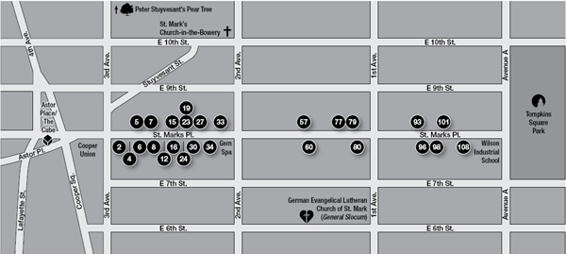

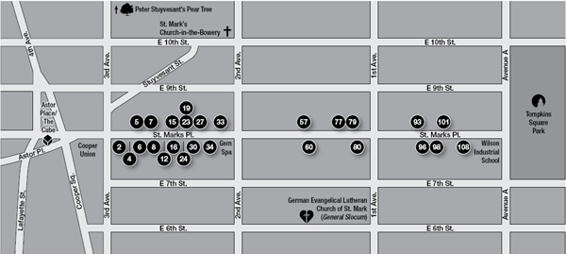

St. Marks Place evangelists insist the street is not just special for them, but that it has affected everyonewhether they know it or notby pioneering everything from preschool, at no. 93 St. Marks Place, to prewashed jeans (no. 24). More than forty songsby musicians as diverse as Lou Reed, the Replacements, and Tom Waitsname-check the street. Nearly all of these songs are about getting drunk or high; many also describe loss, posturing, and sunsets. (The Dictators Avenue A manages to work in all of the above.)

While the revolutionary Leon Trotsky, the painter Joan Mitchell, and the lunatic GG Allin lived elsewhere before or after their time on St. Marks Place, by residing at no. 77, no. 60, and no. 2, respectively, they all joined, whether they meant to or not, a cult stretching backward and forward in time. St. Marks Place devotees often call the street hallowed ground.

But the history of St. Marks Place is more complex than even many of its cheerleaders realize. The street has undergone constant, and surprising, evolution. In the 1600s, this land was Dutch director general Peter Stuyvesants farm. In the 1830s, prominent statesmen lived here. In 1904, it was devastated by New Yorks deadliest tragedy before the terrorist attacks of 2001. In the early twentieth century, gangsters and bootleggers thrived. In the 1940s, it was a working-class immigrant neighborhood; a man who grew up on the street around the time of World War II told me that, as a kid, he chose his route home from school based on whether he preferred to be beaten up by Polish or Italian toughs that day.

The street has been rich and poor and rich again. The cycle of wealth and poverty has spun like a wheel for four hundred years. The street is prosperous now, featuring comically high rents and shimmering new glass buildings. But it is insanity to think, as a friend of mine recently suggested over lunch at one of the many busy new restaurants on St. Marks Place, that rents will keep going up foreverthat a place where change has come so often will never change again.

Even so, some things about St. Marks have remained constant: This part of the city has always welcomed runaways. In the seventeenth century, Stuyvesant took refuge here from the noise and commerce at the tip of the island. In the late 1800s, Peter Cooper, Juliet Corson, and Sara Curry founded peaceful schools on St. Marks to help the poor escape their overcrowded tenements. And since the middle of the twentieth century, kids from all over the country, and the world, who wanted to be writers or artists or do drugs have come to St. Marks Place to find one another and themselves.

Disillusioned St. Marks Place bohemiansthose who were Beats in the fifties, hippies in the sixties, punks in the seventies, or anarchists in the eightiesoften say the street is dead now, with only the time of death a matter for debate. Typically they say the street ceased to be itself in the late 1980s: 1988, say, when the Gap opened, heralding the arrival of corporate national franchises, or 1989, when Billy Joel desecrated the street by using it as a backdrop for his chipper A Matter of Trust video.

Theyre not wrong; the St. Marks Places of the Beats, hippies, and punks are dead. But this book will show that every cohorts arrival, the flowering of its utopia, killed someone elses. Older Slavic and Puerto Rican residents thought everything went to hell when unwashed artists started commandeering their front stoops to promulgate the virtues of free love and Communism. Native Americans could cite the 1640s, when the Stuyvesant family turned their glorious hunting grounds, bountiful for millennia, into a sprawling Dutch farm.

There goes the neighborhood has been heard on the street in many tongues ever since. Someone is probably saying it right now. A college student told me that St. Marks Place died just a couple of years ago with the closing of the Cooper Union Starbucksa business that was initially hailed as the final nail in the streets coffin. As students, James Estrada and his friends lounged there all day free of hassle. I came back from break, says Estrada, and it was gone. We used to hang out there and get cups and fill them with strawberry champagne and feel glamorous. Theres no room for life to be lived there now. The gentrified are gentrifiers who stuck around.

Next page