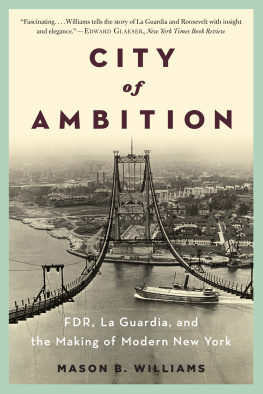

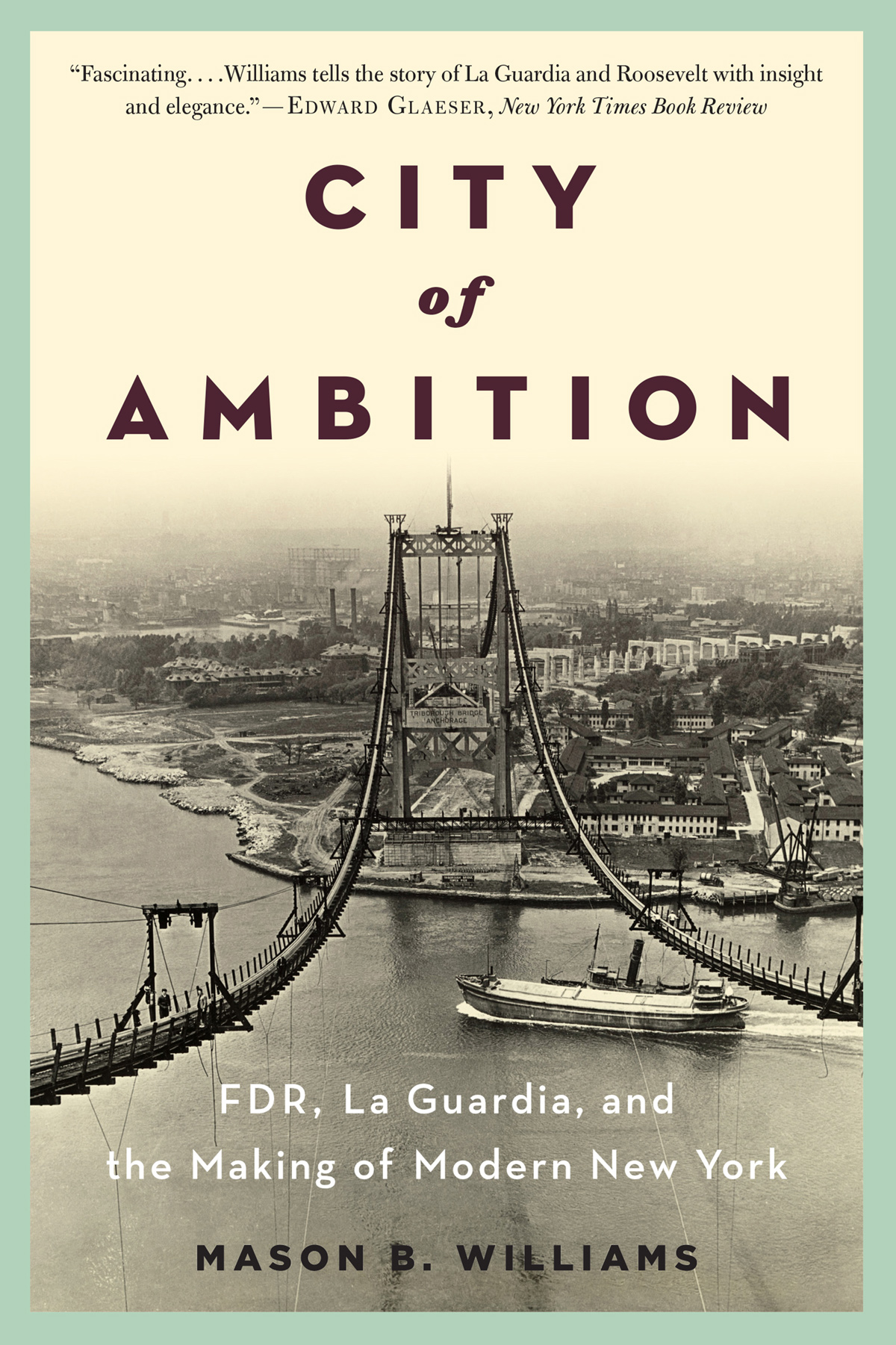

CITY OF AMBITION

FDR, LA GUARDIA,

AND THE MAKING OF

MODERN NEW YORK

MASON B. WILLIAMS

For Alexis

In another few years, New York will have eight million people. It will do more than one-sixth of the business of all of the United States. As war tears the vitals out of the great cities of Asia and Europe, the countries of the world must look to New York as the center of progress, international culture, and advance. Maybe this ought not to be so; maybe the country ought to be centralized. But I know that is not happening.

You will see that New York has collectivized great masses of its enterprise. I am not arguing whether this is good or bad. I am merely pointing out that it must be so: eight million people crowded together do this automatically....

New Yorks relations with Washington will be even closer than New Yorks relations with Albany. I dont know whether this will be a good or a bad [thing]; but I know that it will be so.

Adolf A. Berle, Jr., 1937

These men certainly had tremendous advantages, one working with the other to accomplish similar purposes.

Reuben Lazarus, 1949

CONTENTS

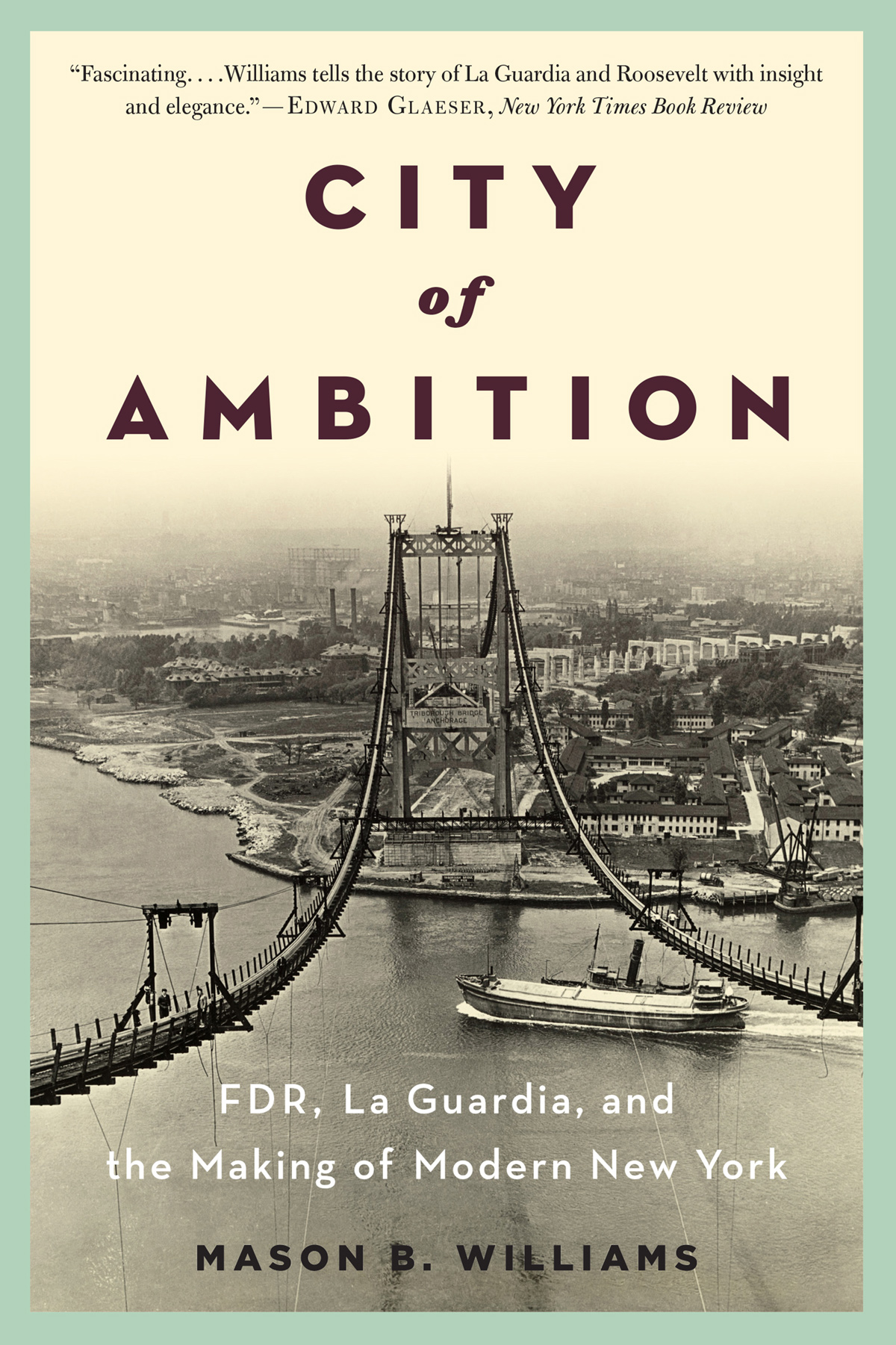

T oday, many New Yorkers take the FDR to get to La Guardia. If their journeys originate in Manhattan north of 42nd Street, they may pass beneath Carl Schurz Park en route to the Triborough Bridge, which will carry them over the sites of the old Randalls Island Stadium and the Astoria Pool before depositing them on Long Island. If they leave from south of 42nd Street, they may cross under the East River by way of the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, entering the borough of Queens not far south of the Queensbridge Houses and passing within a few blocks of William Cullen Bryant High School. These and many similar structures are physical remnants of a time when the federal government under Franklin Roosevelt met the greatest domestic crisis of the twentieth century by putting unemployed men and women to work on public projects largely designed and carried out by local governments. In New York City, Roosevelts partner was Mayor Fiorello La Guardia.

Other monuments from this time remain lynchpins of the citys infrastructure: the Lincoln Tunnel, Henry Hudson Drive, the Belt Parkway. Countless more, stretching from Orchard Beach in the Bronx to the Franklin D. Roosevelt boardwalk on Staten Islands south shore, have become part of the landscape within which life is lived in New York. In a city whose favorite amusements have long included putting up and pulling down, these projects have endured. And yet if the physical legacy of the New Deal still pervades the city, the history that produced it is only dimly understood. The public works projects of the 1930s stand today as mute testaments to an era of tumult and creativity, and to a conception of government which reached its apotheosis in interwar America and which shaped New York City profoundlybut whose history, obscured in turns by ideology and neglect, is too little known.1

This book is an account of the relationship between two of the most remarkable political leaders of the twentieth century: Franklin Roosevelt, the thirty-second president of the United States, and Fiorello La Guardia, the ninety-ninth mayor of New York City. The products of starkly different personal backgrounds and reform traditions, they rose in counterpoint through the ranks of New York politics before coming together in the 1930s to form a political collaboration unique between a national and a local official. Sworn in as the executives of Americas two largest governments at the depths of the Great Depression, they kept the nations biggest city together during one of the most trying periods in its history and helped to establish the course of its politics in the postwar decades.2

It is also a study of how government came to play an extraordinarily broad role in a quintessentially market-oriented cityof how the public sphere, embodied physically in the structures and spaces built up and carved out in the 1930s, was forged. This story has its roots in the Progressive Era, which marked the beginning of a decades-long debate over the ideal relationship among individuals, society, and government.3 In a modern, interdependent society, what rights did each of these groups possess, and what responsibilities? And how could collective action be deployed in the interest of social progress? Particularly in urban politics, the Progressive Era witnessed the introduction of a new set of policy approaches meant to improve the quality of life, mitigate the social costs of capitalist urban development, and render government more efficient and effective.

A crucial moment in this history came in the 1930s. During that turbulent decade, Franklin Roosevelt and his Democratic Party chose to channel the resources of the federal government through the agencies of Americas cities and counties. Fiorello La Guardias coalition of reformers, Republicans, social democrats, and leftists rebuilt New Yorks local state, chasing the functionaries of the citys fabled Tammany Hall political machine from power and implanting a cohort of technical experts committed to expanding the scope of the public sector. As depression gave way to war, the experience of total mobilization politicized market transactions, allowing grassroots activists and political leaders alike to make fair employment and fair prices a central part of city politics.

THE BOOK S TITLE, borrowed and adapted from Alfred Stieglitzs famous photograph of the lower Manhattan skyline, suggests its principal theme. New York in depression and war was a city of decidedly public ambitions: if Stieglitzs skyscrapers captured the ebullient commercialism of the early twentieth century, the New York of the thirties and forties was, as one of its sons has recalled it, a city of libraries and parks.4 It was also a city of municipal markets and public radio, of neighborhood health clinics and free adult education classes, of model housing, of bridges and tunnels and airports intended to integrate the five boroughs and to link the city to the metropolitan region and the wider world. Under La Guardias leadership, the city built a physical infrastructure in which commerce could thrive and the interdependent processes of urban enterprise function efficiently. It also expanded the provision of public goods and services, envisioning these programs as means of lifting or mitigating constraints which impeded the happiness of individuals, families, and communities as they went about their livesconstraints such as unemployment, poverty, high prices, poor health, inadequate housing, a shortage of educational and recreational opportunities, and a stifling urban environment. During the Second World War, it sought to afford city dwellers protection from high prices and rents and to make available useful information to help them navigate consumer markets. These efforts were linked ideologically by the core belief that government should act as the mechanism by which the great productive energies and scientific and technological advantages of the age could be channeled to produce social progress. They were linked operationally by their self-conscious reliance on government as a technology of public action.5

This is, then, a history of public economya history of the ways in which government acted to produce wealth and shape the distribution of wealth in a society whose bedrock commitments include a separation between property and sovereignty, at a particular moment in time. That history took shape against the immediate background of the Great Depression and the Second World War, both national crises which forced Americans to search for new means of collective action. It was formed within the context of a broad shift in the American political landscape, as the lineaments of the American federal system, the relation between local and national authority, were being renegotiated.

Next page