Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Eve Marko and Bernie Glassman Mayumi Oda and Kazuaki Tanahashi with boundless gratitude

I VE WALKED WITH Roshi Joan Halifax on the old traders trails through the Tibetan plateau and straight up the pathless sides of mountains in New Mexico into the high country of clear streams and summer thunderstorms. I know shes circumambulated the great pilgrimage mountain of Kailash many times, wandered alone in the deserts of North Africa and northern Mexico, walked all over Manhattan, done walking meditation in her own Zen center and in many temples on both sides of North America and throughout Asia. She has broken glass ceilings on her journey as a medical anthropologist, Buddhist teacher, and social activist, and shes brought many along with her. Shes a clearheaded and fearless traveler, and in this book she recounts what shes learned in journeys through areas many of us are just beginning to map or notice or admire on the horizon of individual and social change.

We have undergone a revolution in our understanding of human nature in the past few decades. It has overthrown assumptions laid down in many fields that human beings are essentially selfish and our needs essentially privatefor material goods, erotic joys, and family relationships. In disciplines as diverse as economics, sociology, neuroscience, and psychology, contemporary research reveals that human beings originate as compassionate creatures attuned to the needs and suffering of others. Contrary to the 1960s tragedy of the commons argument that we were too selfish to take care of systems, lands, and goods owned in common, variations on such systemsfrom grazing rights in pastoral societies to Social Security in the USAcould and in many places does work very well. (Elinor Ostrom, whose work explored successful economic cooperation, became the only woman to date to win a Nobel Prize in economics.)

Disaster sociologists have also documented and demonstrated that during sudden catastrophes such as earthquakes and hurricanes, ordinary human beings are brave, improvisationally adept, deeply altruistic, and often find joy and meaning in the rescue and rebuilding work they do as inspired, self-organized volunteers. Data also shows that it is hard to train soldiers to kill; many of them resist in subtle and overt ways or are deeply damaged by the experience. There is evidence from evolutionary biology, sociology, neuroscience, and many other fields that we need to abandon our old misanthropic (and misogynist) notions for a sweeping new view of human nature.

The case for this other sense of who we really are has been building and accumulating, and the implications are tremendous and tremendously encouraging. From this different set of assumptions about who we are or are capable of being, we can make more generous plans for ourselves and our societies, and the earth. It is as though we have made a new map of human nature, or mapped parts of it known through lived experience and spiritual teachings but erased by Western ideas of human nature as callous, selfish, and uncooperative, and of survival as largely a matter of competition rather than collaboration. This emerging map is itself extraordinary. It lays the foundation to imagine ourselves and our possibilities in new and hopeful ways; and suggests that much of our venality and misery is instilled but not inherent or inevitable. But this map has been, for the most part, a preliminary sketch or an overview, not a travelers guide, step by step.

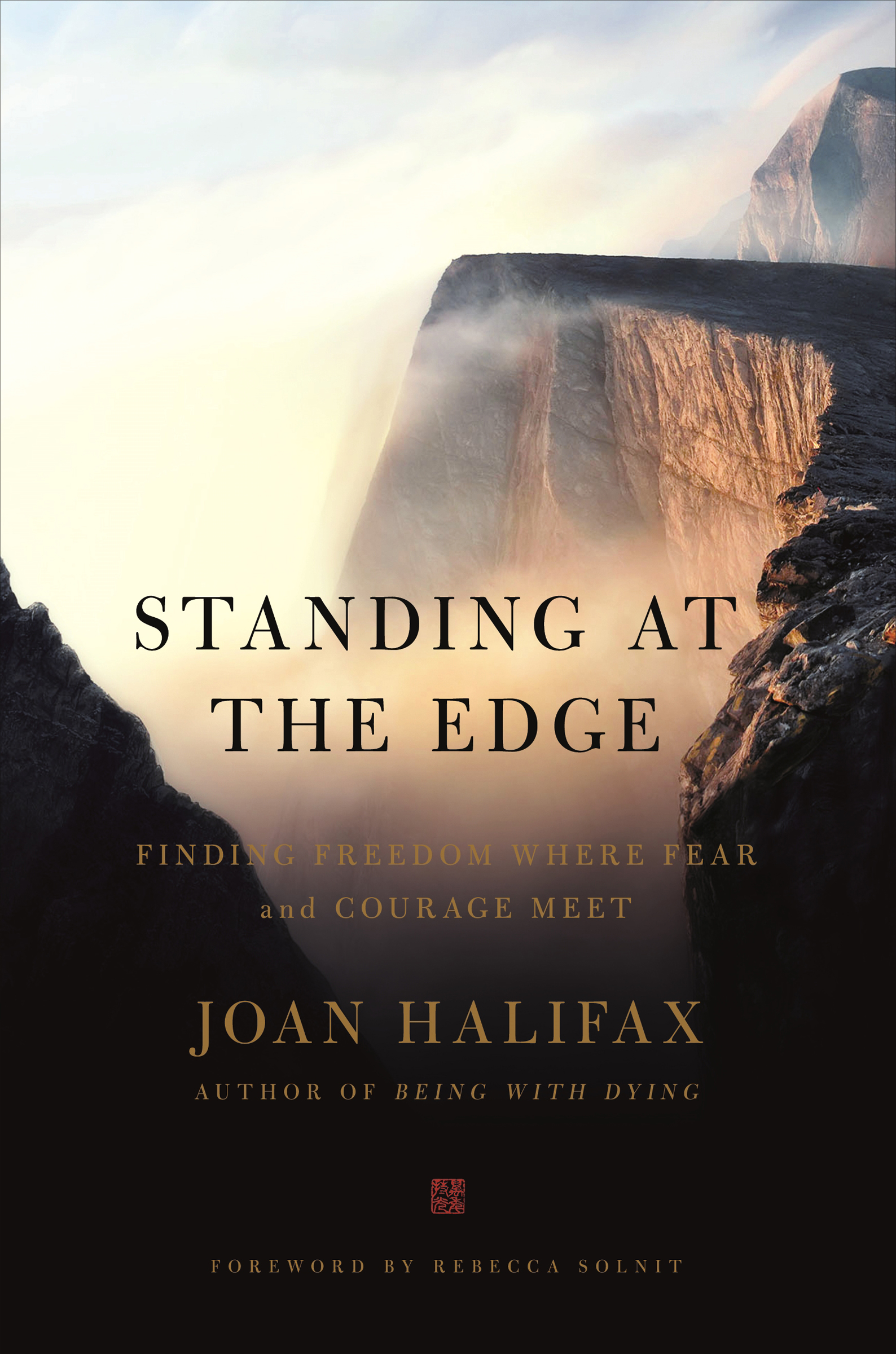

That is to say, most of this work points to a promised land of a better, more idealistic, more generous, more compassionate, braver self. Yet the hope that merely becoming this better self is enough may be nave. In our best self, even on our best days, we run into obstacles, including empathic distress, moral injury, and a host of other psychic challenges that Joan Halifax charts so expertly in Standing at the Edge . She shows us that being good is not a beatific state but a complex project. This project encompasses the whole territory of our lives, including our fault lines and failures.

She offers us something of extraordinary value. She has traveled these realms, learning deeply from her own experiences and those of others, including both those who suffer and those who strive to alleviate suffering, and she has come to know how the attempt to alleviate suffering can bring on its own pain and how to steer clear of that misery and draining of vitality. She has gone far and wide in these complex human landscapes and knows that they are more than lands of virtue shining in the distance. She has seen what many only point to from afarthe dangers, pitfalls, traps, and sloughs of despond, as well as the peaks and possibilities. And in this book she offers us a map of how to travel courageously and fruitfully, for our own benefit and the benefit of all beings.

Rebecca Solnit

T HERE IS A SMALL CABIN in the mountains of New Mexico where I spend time whenever I can. It is located in a deep valley in the heart of the Sangre de Cristo Range. Its a strenuous hike from my cabin up to the ridge at more than twelve thousand feet above sea level, from where I can see the deep cut of the Rio Grande, the rim of the ancient Valles Caldera volcano, and the distinctive mesa of Pedernal, where the Din say First Man and First Woman were born.

Whenever I walk the ridge, I find myself thinking about edges. There are places along the ridgeline where I must be especially careful of my footing. To the west is a precipitous decline of talus leading to the lush and narrow watershed of the San Leonardo River; to the east, a steep, rocky descent toward the thick forest lining the Trampas River. I am aware that on the ridge, one wrong step could change my life. From this ridge, I can see that below and in the distance is a landscape licked by fire and swaths of trees dying from too little sun. These damaged habitats meet healthy sections of forest in borders that are sharp in places, wide in others. I have heard that things grow from their edges. For example, ecosystems expand from their borders, where they tend to host a greater diversity of life.

My cabin sits on the boundary between a wetland fed by deep winter snow and a thick spruce-fir forest that has not seen fire in a hundred years. Along this boundary is an abundance of life, including white-barked aspen, wild violet, and purple columbine, as well as the bold Stellers jay, the boreal owl, ptarmigan, and wild turkey. The tall wetland grasses and sedges of summer shelter field mice, pack rats, and blind voles that are prey for raptors and bobcats. The grasses also feed the elk and deer who graze in the meadows at dawn and dusk. Juicy raspberries, tiny wild strawberries, and tasty purple whortleberries cover the slopes holding our valley, and the bears and I binge shamelessly on their bounty come late July.

I have come to see that mental states are also ecosystems. These sometimes friendly and at times hazardous terrains are natural environments embedded in the greater system of our character. I believe it is important to study our inner ecology so that we can recognize when we are on the edge, in danger of slipping from health into pathology. And when we do fall into the less habitable regions of our minds, we can learn from these dangerous territories. Edges are places where opposites meet. Where fear meets courage and suffering meets freedom. Where solid ground ends in a cliff face. Where we can gain a view that takes in so much more of our world. And where we need to maintain great awareness, lest we trip and fall.