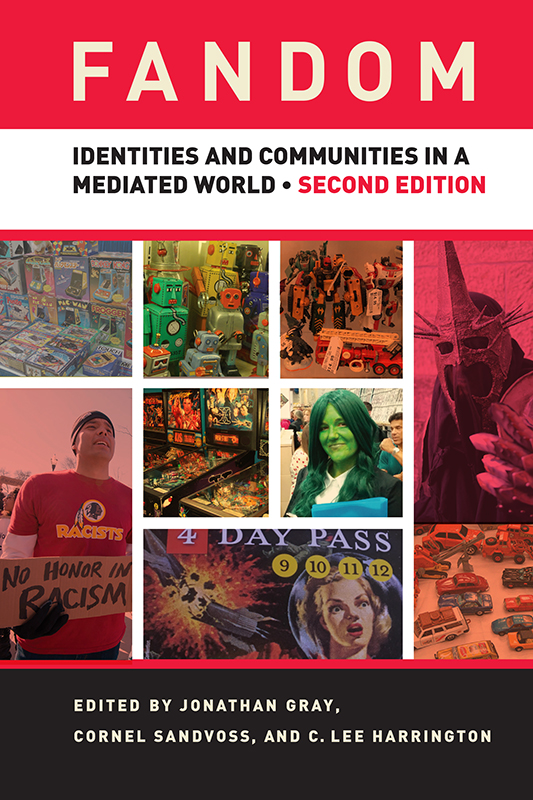

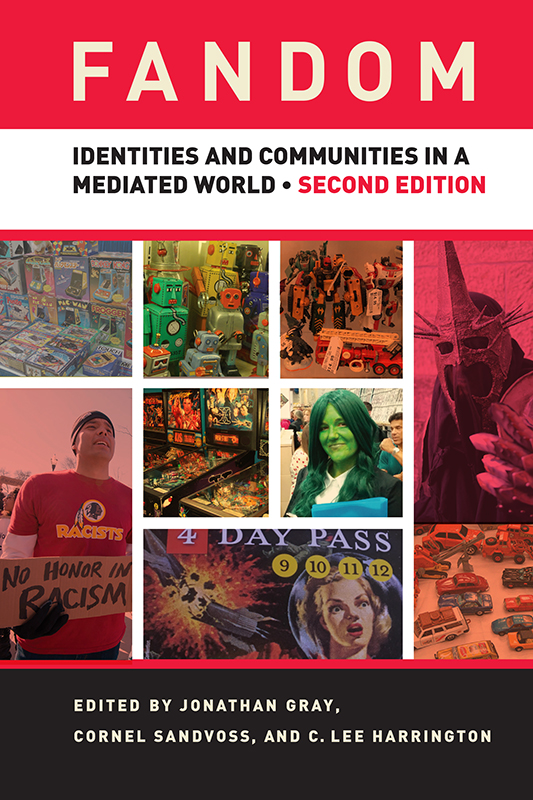

Fandom

Fandom

Identities and Communities in a Mediated World

Second Edition

Edited by Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2017 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-8113-0 (hardback)

ISBN : 978-1-4798-1276-9 (paperback)

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

Cornel Sandvoss, Jonathan Gray, and C. Lee Harrington

Cornel Sandvoss

Kristina Busse

Matt Hills

Rebecca Tushnet

Katriina Heljakka

Daniel Cavicchi

Lucy Bennett

Mark Duffett

Will Brooker

Lori Hitchcock Morimoto and Bertha Chin

Melissa A. Click

Denise D. Bielby and C. Lee Harrington

Henry Jenkins

Alexis Lothian

Jonathan Gray

Abigail De Kosnik

Aswin Punathambekar

Dayna Chatman

Lori Kido Lopez and Jason Kido Lopez

Mizuko Ito

Anne Gilbert

Derek Johnson

Suzanne Scott

Philip M. Napoli and Allie Kosterich

Why Still Study Fans?

Cornel Sandvoss, Jonathan Gray, and C. Lee Harrington

Most people are fans of somethingwith this assertion we began the first edition of this anthology in 2007. Today, following continued technological, social, and cultural changes, fandom is an even more commonplace experience. The proliferation and simultaneous transformation of fandom are well illustrated, for instance, by the emergence of fan as a common description of political supporters and activists. Shortly after the first edition of this volume was published, Barack Obamas primary campaign illustrated the capacity of grassroots enthusiasm through the now-existent infrastructure of social media (combined with the effective management of mainstream media) to transform his outsiders bid into a two-term presidency. Much of what set Obamas 2008 campaign apart from its predecessors were the enthusiasm, emotion, and affective hope that his supporters, voters, fans invested in that campaign.

Much has happened since the celebrations of Obamas election in November 2008. In the world of entertainment, streaming is now a commonplace route to access music, television, and film for many households across the world. The acceleration of the shift from physical media to digital distribution channels has created new incentives for telecommunication providers and online retailers to gain controlling stakes in content rights and production, echoing similar efforts of media hardware manufacturers in the 1980s with the arrival of home VCRs. DVD rental turned streaming service Netflix and online retailer Amazon are creating and/or co-funding serial fan objects from House of Cards to The Man in the High Castle at increasing rates, and Netflix regularly resurrects canceled or former fan-favorite programming. In Britain, former state monopoly telecoms provider BT was so concerned by Rupert Murdochowned Skys push into its domain of landline and Internet service provision that it acquired extensive soccer rights for the UK market as a response, pushing the value for domestic Premier League TV rights past seven billion dollars for 201619 (BBC 2015). These examples illustrate how the unparalleled availability of mediated content and entertainment via digital channels combined with the difficulties to monetize content in digital environments have put fans at the heart of industry responses to a changing marketplace.

As a consequence, representations of fans in mainstream media content have at times shifted away from pathologization to a positive embrace of fans vital role for contemporary cultural industries, and are now commonly part of the narratives that constitute the textual fields of (trans)media events from the cinematic release of the latest Star Wars installment to global sporting events such as the Olympics. Were all fans now has become a familiar refrain in countless popular press think pieces, and was even the marketing slogan for the fifty-second Grammy Awards in 2010. And (a very particular form of) fan banter and identities have even been central to one of the most successful and lucrative television shows of the past decade, The Big Bang Theory, while The Walking Deads aftershow featuring fan debriefing of the nights episode, Talking Dead, often out-rates many otherwise hit shows. Yet with these changing and proliferating representations of fandom, a crucial point of reference to (early) fan studies has shifted, too.

Three Waves of Fan Studies Revisited

In the introduction to our first edition, we divided the development of the field of fan studies into three waves with diverging aims, conceptual reference points, and methodological orientations. The first wave was, in our reading, primarily concerned with questions of power and representation. To scholars of early fan studies, the consumption of popular mass media was a site of power struggles. Fandom in such work was portrayed as the tactic of the disempowered, an act of subversion and cultural appropriation against the power of media producers and industries. Fans were associated with the cultural tastes of subordinated formations of the people, particularly those disempowered by any combination of gender, age, class, and race (Fiske 1992: 30). Within this tradition that was foundational to the field of fan studies and that spanned from John Fiskes work to Henry Jenkinss (1992) canonical Textual Poachers, fandom was understood as more than the mere act of being a fan of something: it was seen as a collective strategy to form interpretive communities that in their subcultural cohesion evaded the meanings preferred by the power bloc (Fiske 1989). If critics had previously assumed fans to be uncritical, fawning, and reverential, first-wave scholarship argued and illustrated that fans were active, and regularly responded, retorted, poached. Fan studies therefore constituted a purposeful political intervention that set out to defend fan communities against their ridicule in the media and by non-fans.

In its ethnographic orientation and often advanced by scholars enjoying insider status within given fan cultures, the first wave of fan studies can be read as a form of activist research. And thus we referred to this wave as Fandom Is Beautiful to draw parallels to the early (and often rhetorically and inspirationally vital) stages of identity politics common for other groups hitherto Othered by mainstream society. Similarly, early fan studies did not so much deconstruct the binary structure in which the fan had been placed as they tried to differently value the fans place in said binary: consumers not producers called the shots. As such, and in this defensive mode of community construction and reinforcement, early fan studies regularly turned to the very activities and practicesconvention attendance, fan fiction writing, fanzine editing and collecting, letter-writing campaignsthat had been coded as pathological by critics, and attempted to redeem them as creative, thoughtful, and productive.

Next page