Carr - Studies in Revolution

Here you can read online Carr - Studies in Revolution full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1972, publisher: GROSSET&DUNLAP; UNIVERSAL LIBRARY EDITION edition (1972), genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Studies in Revolution

- Author:

- Publisher:GROSSET&DUNLAP; UNIVERSAL LIBRARY EDITION edition (1972)

- Genre:

- Year:1972

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Studies in Revolution: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Studies in Revolution" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Carr: author's other books

Who wrote Studies in Revolution? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Studies in Revolution — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Studies in Revolution" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

PREFACE

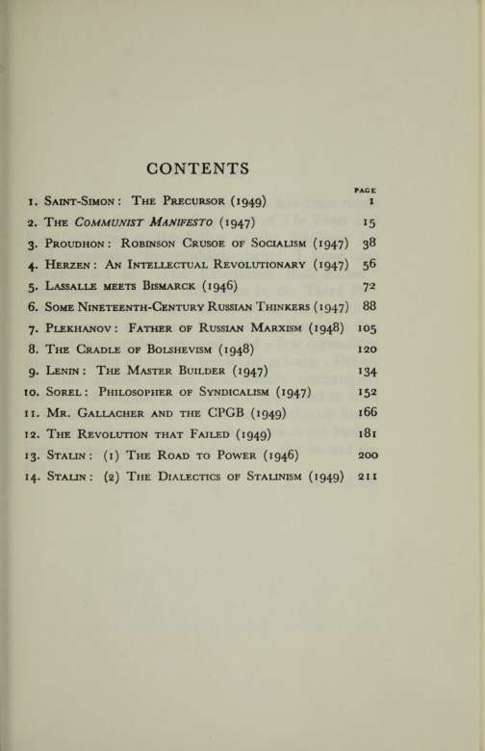

The articles out of which this book has been made appeared in the Literary Supplement of The Times and I am indebted to the Editor of the Supplement for kind permission to republish them: I have also incorporated in " The Revolution that Failed" some passages from a talk given in the Third Programme of the British Broadcasting Corporation. A few topical references have been adjusted, a few cases of overlapping removed, and a few corrections made to meet criticisms, public or private. Otherwise the articles appear substantially unchanged; the year of original publication is appended to each in the list of contents. Of the two articles on Stalin with which the volume ends, the first was the earliest item in the collection to be written, the second the

last.

E. H. CARR

SAINT.SIMON: THE PRECURSOR

Henri de saint-simon was an intellectual eccentric. He was a member of an aristocratic family who abandoned his title of Comte with a dramatic gesture in the French Revolution and spent most of his life in penury; a rationalist and a moralist; a man of letters who never succeeded in writing or completing any coherent exposition of his ideas; and, after his death, the eponymous father of a sect devoted to the propagation of his teaching, which enjoyed a European reputation. Saint-Simon lacked most of the traditional attributes of the great man. It is never easy to distinguish between what he himself thought and the much more coherent body of doctrine, some of it astonishingly penetrating, some not less astonishingly silly, which the sect built up round his name. It is certain that posterity has read back into some of his aphorisms a greater clarity and a greater significance than he himself gave to them. But the study of Saint-Simon often s eems t o suggest that the great French Revolution , not content with the ideas which inspired its leaders and which it spread over the contemporary world, also projected into the future

Studies in Revolution

( a fresh ferment of ideas which, working beneath the \ surface, were to be the main agents of the social < and political revolutions of one hundred years to (^ come.

Of these ideas Saint-Simon provided the first precipitation on the printed page. No one who writes about him can avoid applying to him the word " precursor ". He was the precurs or of socialism, the precursor of the technocrat s, the precursor of ^r totalitarianism all these labels fit, not perfectly, but, considering the distance of time and the originality of the conceptions as first formulated, with amazing appositeness. Saint-Simon died at the age of sixty-five in 1825, on the eve of a period of unprecedented material progress and sweeping social and political change; and his writings again and again gave an uncanny impression of one who has had a hurried preview of the next hundred years of history and, excited, confused and only half understanding, tried to set down disjointed fragments of what he had seen. He is the type of the great man as the reflector, rather than the maker, of history.

The approach of Saint-Simon to the phenomenon of man in society already has the modern stamp. In 1783, at the age of twenty-three, he had recorded his fife's ambition : " Faire un travail scientifique utilearhumanite". Sa int-Simon marks the transition^ from the deductive rationalism of the eighteenth to the inductive rationalism of the nineteenth century from metaphysics to science. _He inaugurates_ the c ult of science and of the scientific method. He rejects equally the " divine order" of the theo

Saint-Simon: The Precursor

logians and the " natural order " of Adam Smith and the physiocrats. In his first published writing, Lettres d'un habitant de Geneve, he enunciated the principle that " social relations must be considered as physiological phenomena ". Or again : " The que stion of social organization must be treated abs olutely in the same way as any other scientific question *\ The term " sociology was apparently the invention of Saint-Simon's most famous pupil, once his secretary, Auguste Comte. But the idea came from the master himself and was the essence of his philosophy.

Another of Saint - Simon's pupils, Augustin Thierry, was to become a famous historian; and there is in Saint-Simon not only an embryonic sociology, but an embryonic theory of history which looks forward to a whole school from Buckle to Spengler. /History)is a study of the scientific laws governing human development, which is divided into " epoques organiques " and into " epoques critiques " ; and the continuity of past f present and f uture is clearly established . " History is social physics." No doubt later nineteenth-century and twentieth-century theories of history owe more to Hegel than to Saint-Simon. But they owe most of all to Karl( Marx ^) who combined the metaphysical historicism ot Hegel with Saint-Simon's sociological ** utilitarianism.

But perhaps Saint-Simon's most original insight original enough at a moment when the French Revolution had consecrated the emancipation and enthronement of the individual after a struggle of

Studies in Revolution

three centuries was h is vision of t he coming, resubordination of the individual to society. Saint-Simon, though no partisan of revolution in principle (he once said flatly that dictatorship was preferable to revolution), never abated his enthusiasm for the revolution which had overthrown the ancien regime. " La feodalite " was always the enemy ; incidentally, it may well be due, directly or indirectly, to Saint-Simon that " feudalism" became Marx's chosen label for the pre-bourgeois order of society. Nearly all Saint-Simon's contemporaries, and most western European thinkers for at least two generations to come, took it for granted that liberalism was the natural antithesis, and therefore the predestined successor, of " feudalism ". Saint-Simon saw no reason for the assumption. He was not a reactionary, nor even a conservative; but he was not a liberal either. He was something different and new.

It was clear to Saint-Simon that, after Descartes and Kant, after Rousseau and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the cult of individual liberty, of the individual as an end in himself, could go no farther. There are some astonishingly modern echoes in a collection of essays under the title U Industrie, dating from 1816 :

The Declaration of the Rights of Man which has been regarded as the solution of the problem of social liberty was in reality only the statement of the problem.

A passage of Du systeme industries in which Saint-Simon a few years later sought to establish the new historical perspective, is worth quoting in full:

Saint-Simon: The Precursor

The maintenance of liberty was bound to be an object of primary attention so long as the feudal and theological system still had some power, because then liberty was exposed to serious and continuous attacks. But to-day one can no longer have the same anxiety in establishing the industrial and scientific system, since this system must necessarily, and without any direct concern in the matter, bring with it the highest degree of liberty in the temporal and in the social sphere.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Studies in Revolution»

Look at similar books to Studies in Revolution. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Studies in Revolution and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.