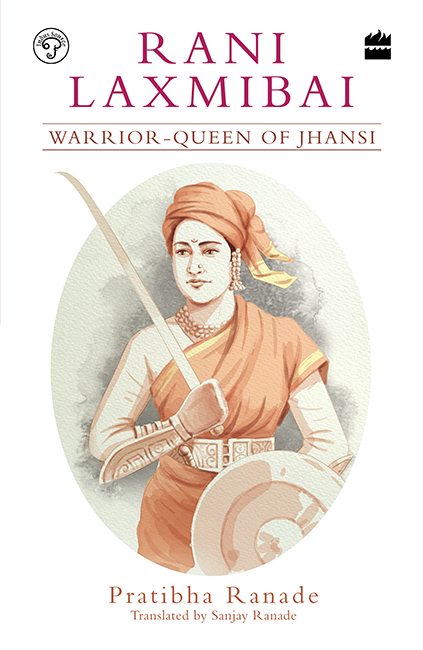

Pratibha Ranade - Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi

Here you can read online Pratibha Ranade - Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: HarperCollins India, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins India

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

RANI LAXMIBAI

Warrior-Queen of Jhansi

PRATIBHA RANADE

Translated by Sanjay Ranade

Dedicated to

Janakisharan Varma and Shreeram Gunthe

Contents

Introduction

T he writing of history has always been a vibrantly debated topic of discussion for historians and intellectuals all over the world. The discussion revolves around the method of writing history and the motives behind writing it. Will Durant, the famed historian, writes in The Story of Civilization: The writing of history to a great extent relies on inference and logic. Biases too affect the writing of history somewhat. I would like to add a little to what Durant has said. A writer of history can delve deeper into the historical subtext when he explores the complexities of human nature, relationships, peoples aspirations, their pride and their sense of mortification. The writer also has to comprehend the contemporary social tensions, movements, and the subtle undercurrents flowing silently under the social-political-cultural-religious surface.

In the history of India, the Uprising of 1857 is an extremely important event. Lokmanya Tilak wrote about this Uprising in his editorial for the Kesari of 7 May 1895 titled Jhanshichi Rani (The Queen of Jhansi): There would be a rare human being in India whose mind is not torn apart at the memory of that event. The memory still touches one deeply even today after 150 years. After the Uprising, India came completely under the control of the British. Queen Victoria established British rule by taking over the governance of India from the East India Company. All the princely states, big and small, who had not participated in the Uprising of 1857 continued to rule their own territories and became tributaries of the British Empire. The effects of the Uprising penetrated deep into the psyche of Indians and into Indian politics as well. These effects turned out to be far reaching. Of course, the Uprising greatly affected the British too. India had become their crowning glory. However, at the same time the slaughter of the white- skinned by the Indian soldiers during the Uprising had embedded fear so deep in the minds of the British that when India got its independence in 1947, they were afraid that the Indians would once again slaughter them. Hence, a majority of the British and white-skinned Anglo-Indians left for England before 15 August 1947.

On 26 February 1857, the infantry-cavalry at Behrampur, and Mangal Pandey from the cavalry at Barrackpore, had rebelled by refusing to accept new cartridges given to the army. Rumours had been rampant that these cartridges were greased with cow and pig fat. On 3 May, the cavalry at Lucknow rebelled for the same reason. The British punished those who rebelled, sent some of them away to be a part of the army at China, and hanged the rebel sepoys Mangal Pandey and Eshwar Pandey on 8 April and 21 April respectively. Thereafter, on 10 May 1857, the sepoys of Meerut rebelled and within no time the rebellion had spread to all of Northern India. Since then, whether this Uprising was a rebellion by the sepoys or a war for independence has been a topic of intense discussion and differing opinions.

The rebellion first started with the sepoys but soon included the rulers of the states and the common people too. Although they all joined the rebellion against a common enemy, their reasons for participating in it differed. The rulers fought the British out of self-interest in retaining their kingdoms. They had no vision of an independent India. The sepoys, on the other hand, fought because they did not want to serve the British, they did not want foreign rule, and therefore after the rebellion they reinstalled their previous kings as rulers. The Meerut sepoys reinstated Bahadur Shah Zafar on the throne when they came to Delhi, the Kanpur sepoys wanted Nana Saheb to rule as the Peshwa, and similarly the sepoys of Jhansi forced Rani Laxmibai to take over as their ruler. The horror that their religion would be corrupted while breaking the cartridges on which pig and cow fat was applied led the sepoys to take up arms. There was no idea of national or political independence. Those who shared this perspective, called the war the sepoy mutiny or shipai gardi (sepoy mob). Prior to Independence, due to the sensitivity of the times, people called it a mutiny. Even after Independence, several eminent people such as socialist Manavendra Roy, historian and writer Dr. Surendranath Sen, and Dr. R.C. Mujumdar have referred to this Uprising as a mutiny. N.R. Phatak, eminent doctor, social worker and MLA, picked up the same thread and called the rebels a sepoy mob.

They argued that this flare had only spread over a small region in India. Out of all the Indian sepoys who were in the service of the British, only a few soldiers revolted, while the rest fought on the side of the British. Among the common people, many were well-disposed towards the British and, in fact, helped them. The British-educated neo-intellectuals too, leaned towards the British. At the same time, the kings, nobles and landowners had virtually no communication with each other. Everyone was fighting for their own self-interest. There were no visible feelings to unite and fight the British; no nationalist emotion beyond their selfish motives. As a result, the rebel sepoys did not have a gritty, resolute, and nationalist leadership. The revolt was scattered and the British curbed it with the help of the Hindu kings and nobles, Hindu sepoys, and the common masses. As a result, feudalism was destroyed and India, which until then was a motley gathering of different kingdoms, now emerged as a single nation under the British regime. Antiquated, traditional thoughts found new direction in modern, progressive ideas like individualism, equality, and justice. A single, resolute government provided to the masses assurance, security, and new opportunities. A feeling of gratitude is visible in the writings of some writers. On the occasion of the centenary of the 1857 Uprising, the Government of India published Dr. Mujumdars The Sepoy Mutiny and the Revolt of 1857 and Dr. Sens 1857 in the year 1957, while Phataks Atharashe Sattavanache Shipai Garde (The Sepoy Mob of 1857) was published in 1958.

Peoples Participation

Dr. Sen has stated in his book that in 1857 the issue of India as a nation was in its infancy. This was a fact. This meant that the feeling of nationalism had not taken root in the minds of the people; there was no awakening among them. The common people had a parochial view. They owed allegiance to the local village head, king, emperor or noble who ruled the region they belonged to, rather than the ruler in Delhi. There was a lack of concern among the masses in the more remote regions about who occupied the throne of Delhi. It did not matter who was at the centre, who the emperor was, or whether a Sultan or the Mughals replaced the ruler later. The repeated battles between the kings and nobles were the only things that disrupted their life. Their loyalty was to their own king or ruler. People had been following this order for hundreds of years. The idea of one nation and nationalism originated for the first time in Europe during the Renaissance period. It was the age of the revival of art, architecture, literature, sciences, different branches of knowledge and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, growth of capital economy, and colonialism but the most important factor was the bitter clash between the Roman Church and the European monarchy for political power, which necessitated the spirit of nationalism. Due to the non-existence of similar conditions in India during the nineteenth century, the need for the European model of nationalism was not felt. This consciousness originated in India after 1857 due to the Uprising.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

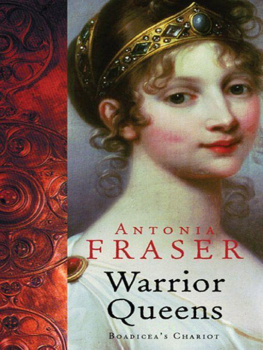

Similar books «Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi»

Look at similar books to Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Rani Laxmibai: Warrior-Queen of Jhansi and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.