HORSE AND RAIL

T he tram and the tramway have had a roller coaster ride in Britain. Both names have been used for more than two hundred years, but their meaning has shifted as well as the technology they represent. In 1800 they referred to the vehicles and tracks of primitive goods railways. Neither name has ever been commonly used in the United States, where the first true street railways were introduced. Early passenger trams there were known simply as horsecars and their mechanised successors have always been called streetcars or trolleys.

The distinction between a tramway and a railway has also been blurred over the years both in legal terminology and in popular use. Although the term light rail has been widely adopted on both sides of the Atlantic since the 1970s, it is a catch-all description rarely used in everyday speech. In the simplest definition today, a tramway is a type of light railway which shares its right of way with other traffic, often on a public highway.

A full-scale railway in the United Kingdom has always had its own defined and authorised right of way, a distinction never strictly applied in the United States. The new generation of light railways built in Britain since the 1980s often combines operation on former railway alignments with sections of urban street running. These are still known in the United Kingdom as tramways, operated by rail vehicles called trams.

At the start of the nineteenth century the terms were almost interchangeable. Both tramway and railway were used to describe the short early plateways on which goods and minerals were transported between mines, canals and harbours. All of them used horse power before the development of reliable steam locomotives in the 1820s. Their freight, usually coal or iron ore, was carried in small open wagons, which were referred to individually as trams or trucks but became trains when coupled together. The primitive iron trackwork enabled horses to pull heavier loads over these tracks than was possible on an uneven road surface.

None of these lines were designed to carry passengers but inevitably some tried it as a sideline to their main business of goods transport. The first recorded passenger operation was on the Oystermouth Railway or Tramroad in South Wales, which advertised a carriage service along the Gower Peninsula from Swansea in 1807. This was essentially a novelty sightseeing attraction for parties of wealthy tourists. Although it continued to operate for some years it was not copied anywhere else in Britain. The Oystermouth tramcar, which resembled a one-horse stagecoach with iron wheels, was a one-off not a prototype or a trendsetter.

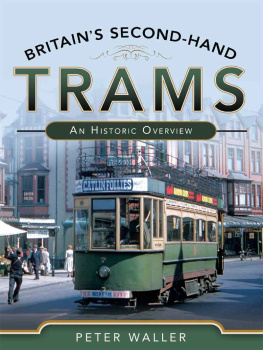

Is this the first or second passenger tramcar built in Britain? A sketch of the original Oystermouth rail carriage at Swansea drawn by Miss J. Alford in 1819. A full-size reconstruction of the car based on this drawing is on display at Swansea Museum.

A tramway providing a regular public transport service on urban streets came many years later in New York City. Urban coach services by omnibus (a fleet name adopted from the Latin meaning for all) were introduced on fixed routes in Paris (1828) and London (1829). Rapidly growing New York followed soon afterwards, where the omnibus owners often had difficulty running their heavy vehicles on the badly made up city streets of Manhattan in winter. It occurred to someone that running horsecars on rails in the road would give a smoother ride and make much more efficient use of horse power.

Coincidentally, the New York & Harlem Railroad Company was given permission in 1831 to build the citys first railway right on the streets. It was only allowed to use animal power in the built-up area of the city. Steam locomotives were banned from the built-up area following a number of boiler explosions. This led directly to the development of a local horsecar service on the new street railway in Manhattan.

The horse-drawn streetcar soon emerged in New York as a distinct vehicle type. It was smaller than a long-distance railroad car but twice the size of a city omnibus. A new form of urban passenger transport had appeared, though it was not immediately emulated in other growing towns in the United States or Europe. In Britain the notion of street railways was already against the law. In the early railway booms of the 1830s and 40s parliamentary permission was only given for railways entering towns and cities on their own right of way and completely separated from the public highway.

In the United States only New Orleans quickly followed New York in opening a horsecar line in 1834. Street railways did not take off in other US cities until the 1850s. One young American trader who was impressed by the new horsecar lines he found in Philadelphia was convinced that the system could appeal to the businessmen of Britain. This was the appropriately named George Francis Train, who arrived in Liverpool in 1859 determined to sell the idea on Merseyside.

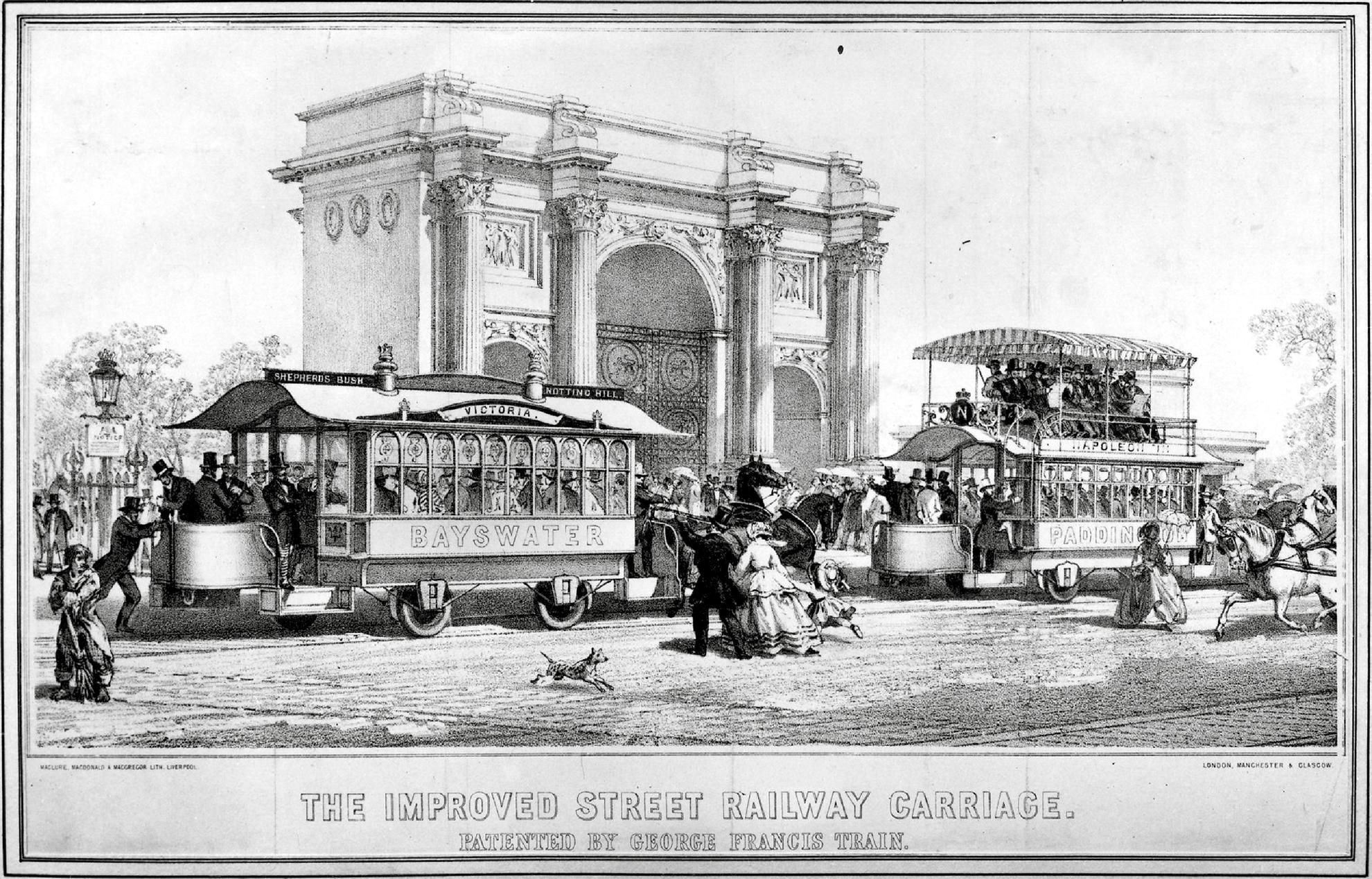

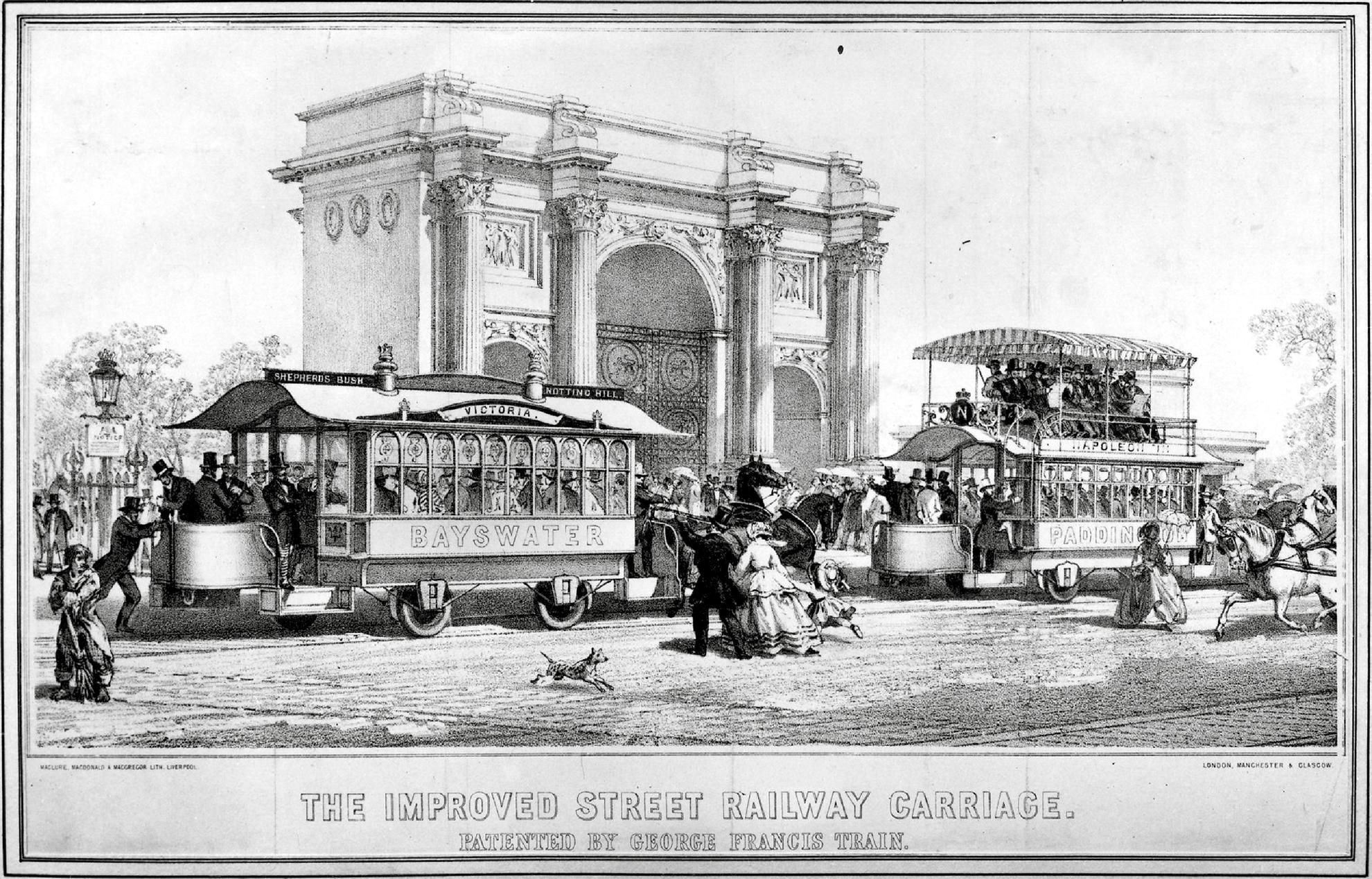

Trains flamboyant and bombastic manner was both a help and a hindrance to tramway development. He managed to launch the first purpose-built street railway in England at Birkenhead in 1860. However, Train soon ran into trouble in London, mistakenly choosing the wealthy areas of Westminster and Bayswater for his early trial lines in the capital. He faced strong opposition from both omnibus operators and carriage owners who claimed that his patent step rail, which protruded above the road surface, was a danger to other vehicles. When Train opened his third London tramway in Kennington he was successfully prosecuted for conspiracy and causing a public nuisance. His rails were removed and Train went back to the United States, defeated by vested interests and legal process even though his tram trials had been quite a success both financially and with the general public.

Only a handful of tramway proposals got through the required parliamentary route to the statute book in the 1860s. Each line had to be authorised by a private (and costly) Act of Parliament but in 1870, bowing to pressure, Parliament passed the Tramways Act, which established a clear set of procedures to be met before a street tramway could be introduced anywhere in Britain.

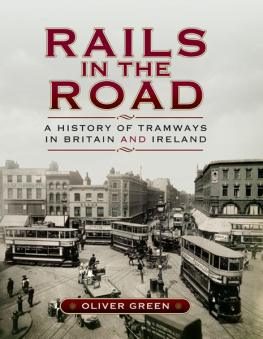

An artists impression of George Trains first proposed street railway in London, 1860. Trains tramway was authorised as a temporary concession but removed after only a few months. The vehicle design is an ornately decorated version of early American horsecars.

The 1870 Act simplified the process, but it was a classic compromise, giving local authorities the power to approve and even build but not actually to operate tramways. A working contract could be awarded to an independent company for a maximum of twenty-one years, after which the council had the right to purchase the tramway company and all its assets at their scrap value.

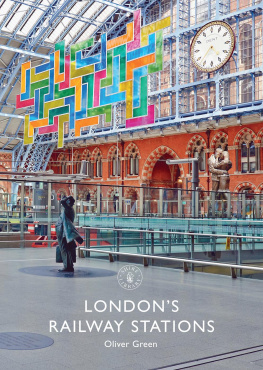

Middle class Londoners comfortably seated in one of the new horse trams introduced in 1870. Cars were soon crowded with travellers of all classes and the American expression straphanger for standing passengers quickly crossed the Atlantic.

Horse tramways now began to appear in towns all over the country. For the previous forty years, omnibuses had catered almost exclusively for the urban middle classes, especially in London. Omnibus fares were high and services started late in the mornings, often after 8:00am. The new tram companies had to provide cheap early morning workmens fares and services were usually running by 5:00am. As each tramcar was twice the size and capacity of an omnibus, the companies could still make a good profit with low fares. It was the start of an urban transport revolution.