Keep

the

Damned

Women

Out

Keep

the

Damned

Women

Out

The Struggle for Coeducation

Nancy Weiss Malkiel

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2016 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Cover design by Amanda Weiss

All Rights Reserved

Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2018

Paper ISBN 978-0-691-18111-0

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition as follows:

Names: Malkiel, Nancy Weiss, author.

Title: Keep the damned women out : the struggle for coeducation / Nancy Weiss Malkiel.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016008822 | ISBN 9780691172996 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: WomenEducation, HigherUnited StatesHistory20th century. | WomenEducation, HigherGreat BritainHistory20th century. | CoeducationUnited StatesHistory20th century. | CoeducationGreat BritainHistory20th century. | Universities and collegesUnited StatesAdministrationHistory20th century.| Universities and collegesGreat BritainAdministrationHistory20th century. | College administratorsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | College administratorsGreat BritainHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC LC1756 .M26 2016 | DDC 371.822dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016008822

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std and Milano

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

To Burt and Piper

Contents

Illustrations

Following page 166

Following page 358

Preface

The 1960s marked a major turning point in elite higher education in the United States and the United Kingdom. As the decade opened, colleges and universities closely resembled the institutions they had been in the 1950s and earlier. By end of the 1960s, so much had changed. The familiar contours of college and university life had been upended and reshaped in profoundly important ways: in the composition of student bodies and faculties, structures of governance, ways of doing institutional business, and relationships to the public issues of the day. That coeducation should come in the context of those many changes is both understandable as part of the larger enterprise of institutional transformation and, at the same time, worthy of special attention and analysis.

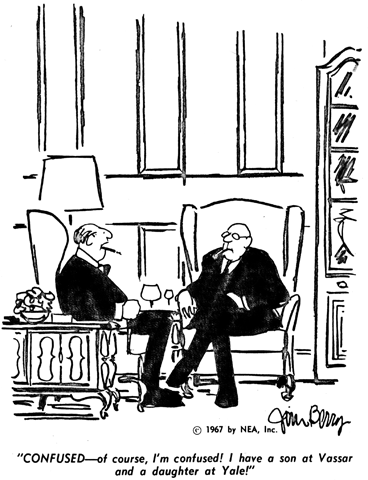

This book focuses on the actions of a small number of the most elite private institutions of higher education in the United States and the United Kingdom, actions taken almost simultaneously in a very brief window of time. Beginning in 1969 and mainly ending in 1974, there was a flood of decisions for coeducation on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. This book addresses these questions: Why did very traditional, very conservative, very elite institutions decide to embark on such a fundamental change? Why did so many schools act in the late 1960s and early 1970s? How was coeducation accomplished in the face of strong opposition? What was the role of institutional leadership? And, with the admission of students of the opposite sex to formerly single-sex schools, what happened? In other words, how well did coeducation work in its early incarnations?

The story begins with Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. It addresses the unusual circumstances of Harvard and Radcliffecoordinate institutions for three quarters of a century but hamstrung in their efforts to move to formal coeducation. It focuses next on the decisions for coeducation at Yale and Princeton, which were the prime movers, first competing with one another for advantage at every turn, then inspiring a wave of decisions at other institutions that watched them closely, learned from their reasoning and research, and responded to their actions. The book turns then to Vassar, the most prominent women's college to embark on coeducation, and looks also at Vassar's Seven Sisters peers, Smith and Wellesley, which investigated admitting men during this period but decided to remain single-sex. The book moves next to Dartmouth, where coeducation came slightly later than at Yale and Princeton and was accompanied by a ferocious reaction that made Dartmouth distinctive for highly problematic behavior toward women students. It then crosses the Atlantic to examine the advent of coeducation at the University of Cambridge, where the first three men's collegesChurchill, Clare, and King'sadmitted women in 1972, and the University of Oxford, where the first fiveBrasenose, Hertford, Jesus, St. Catherine's, and Wadhamfollowed suit in 1974.

This is a transatlantic study, for multiple reasons. First, universities on both sides of the Atlantic were strongly influenced by upheavals of the 1960s, especially the antiwar movement, the student movement, and the women's movement, and it is important to understand how these movements led to fundamental changes in so many of the basic structures and assumptions of university life. Second, decisions for coeducation on both sides of the Atlantic were being taken at the same time, and we need to make sense of their similarities and differences. Third, as we shall see, explicit connections existed between American and British universities and their leaders. What was happening in the United States, particularly at Princeton and Yale, had some influence on what was happening in Oxford and Cambridge, and we need to understand how and why.

Above all, this book is a study in institutional decision-making. It seeks to demonstrate how colleges and universities came to embrace a particular kind of institutional transformation and to take stock of the consequences of their decisions. Therefore, it is important to be clear at the outset that the contexts in and processes by which those decisions were made in the United States were different from those in the United Kingdom. American and British colleges

In the United States, then, college and university presidents played critical roles in the coming of coeducation. Presidents needed to convince their boards to embrace coeducation. They had to harness faculty support; they needed to deal with alumni who had very strong views about coeducation; they needed to mobilize the internal planning and execution to make coeducation happen; and they then needed to find the necessary resources. In the United Kingdom, the situation was different. In the main, decision-making was done college by college rather than in the universities of Cambridge or Oxford as a whole. Leadership on the part of certain principals, wardens, provosts, or masters, as the heads of colleges were variously titled, was certainly important in hastening the advent and effectiveness of coeducation. Nevertheless, some colleges went coed despite the hesitation, or even outright opposition, of their leaders. Such decisions rested with the college fellows, and the 1960s saw notable generational shifts in college fellowships as a younger cohort, newly appointed in that decade, often took the lead in encouraging their colleges to go mixed. There were no trustees to convince, and the role of alumni in Britain was much less consequential than in the United States. These fundamental differences shape the narratives that follow.

Why focus on elite higher education rather than higher education more generally? Elite institutions are not more important than other institutions, but what happens at elite institutions has an outsized influence on other institutions. It would be too simple to say that elite institutions lead and everybody else falls in line. But certainly in the United States, for better or not, many colleges and universities watch closely what goes on at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (and, more recently, Stanford) and seek to model their own programs and initiatives on those institutions. The same is true in the United Kingdom, where Oxford and Cambridge set a tone and provide a model that profoundly influences other institutions.

Next page